By Martha Rhine

“What are you?”

Some people react automatically to that question and move on. For others, it is annoying and disrespectful.

It is a question of race, of course, but why do people ask? To understand others better, or to decide how they feel about them or where they belong?

America is more diverse than ever in 2018, so what’s with the question?

In a recent example, Dominican singer and “Love & Hip Hop: Miami” star Amara La Negra visited the radio show “The Breakfast Club,” where after declaring herself excited to be there, she was pointedly asked by co-host Charlamagne Tha God, “What are you?”

The singer is no stranger to conversations on race and colorism. She identifies as Afro-Latina, a term that is often confusing for people who believe you must be African-American in order to call yourself black.

Amara La Negra’s dark complexion and signature ‘fro have been used against her. She’s been accused of appropriation — of pretending to be something she’s not.

Are you black if you’re not African-American? What if you’re half white and half black? Are you Hispanic if you have blonde hair and blue eyes? Are you Korean if you don’t speak the language?

People of mixed race are accustomed to being asked to define themselves more clearly, and it is not just acquaintances who ask. There is always the dilemma of which box to check on official forms asking: Caucasian, African-American, Asian or Pacific Islander?

In recent years, Hispanic-Latino has been added, but realistically speaking, those define ethnicity, not race. There are black Latinos, white Latinos and many other divergent individuals that make the concept of race so unconvincing to anthropologists.

National Geographic and The New York Times have recently published work on the topic of race and genetics, addressing race as a social construct used to categorize people.

There is security in belonging. Some people have it easier than others; they fit neatly into the boxes society has allocated for them as others struggle to define themselves clearly for a time until they make their choice to live outside the box.

The following people shared their thoughts on race and experiences growing up biracial.

Graham Colton is a graduate student in journalism.

Graham Colton is a graduate student in journalism.

“I’m three-quarters white and one-quarter Asian. I identify more with my white side because that side constitutes the mathematical majority of my racial makeup,” Colton said.

Colton explained he isn’t intimidated by stereotypes of the studious Asian or the white male, and he’s learned to push past them to define himself clearly.

“I don’t need racial stereotypes to help me form my identity anymore, because I’ve pushed past the discomfort of self-discovery into the realm of the self-actualization of my identity, racially and in other respects,” he said.

Colton sees the pressure to define racial identity as a political tool.

“People of different political persuasions value certain racial identities more than others,” Colton said. “As race has become more politicized in this country, I’d imagine that it almost feels invasive for people of any race to be political pawns.”

Colton believes that biracial people are proof that race does not have to be binding.

Angelina Lindsay is a criminology major.

“I’m half Korean, half Caucasian. I feel more pride to be Korean, it’s unique and different,” she said.

Lindsay’s parents are a big influence in her life and have always encouraged her to embrace her unique place in the world. She believes race is a real and present issue.

“It defines a person. It’s a big deal in today’s society, people are discriminated against,” she said.

However, Lindsay considers herself fortunate to have escaped issues of discrimination growing up and feels grateful for that. She wishes people could look past classifying others.

“I’m about embracing everyone: black, white, blue, purple,” she said. Circumstantially, Lindsay’s friends are mostly white. “The Asian friends I do have are family friends. I like hanging out with them, but they speak primarily Korean,” Lindsay said.

Kyla Fields is a mass communications major.

Kyla Fields is a mass communications major.

“I am half Filipino, half white. The white side is mostly Irish, some German, and I guess some English. I just say white,” she said.

Fields’ mother emigrated from the Philippines and met her father at a party. She loves the story of how they met. Growing up, people thought she was adopted when they saw her with her father.

“My dad is so pale it’s crazy,” she said as she laughed.

Fields never focused on her differences during childhood because she was surrounded by extended family who looked like her.

“I got to high school and college and didn’t meet anyone else like me, so I thought, ‘Okay I guess I am kind of different,’” she said.

Fields leans more toward her Filipino roots because of her upbringing surrounded by other Filipino family. She believes being biracial gives her a better perspective on life and fully embraces her culture, but she wishes she knew the language.

“It’s the last thing I’m missing to fully embrace my culture,” she said. “Hopefully one day I’ll learn.”

Tylia Battle is a marine biology major. She is half African-American, half Puerto Rican.

Tylia Battle is a marine biology major. She is half African-American, half Puerto Rican.

“In south Florida most families were biracial,” she said. “I still got picked on because I had big curly hair and people would be like ‘You don’t look black, you speak Spanish.’ They’d also say, ‘You’re not Spanish, look at your hair!’”

Battle remembers being called white for speaking properly.

“I was like, ‘I don’t know what to tell you, this is how I talk,’” she said.

Battle’s childhood was a back-and-forth between her African-American and Hispanic traditions, and she’s thankful for family dynamics that exposed her to different cultures and helped her learn Spanish, for instance.

“My grandparents didn’t speak English,” she said. “So I learned a lot of Spanish because that was how I talked to them.”

Jake Troyli is a graduate student getting his masters of fine arts with a concentration in painting.

Jake Troyli is a graduate student getting his masters of fine arts with a concentration in painting.

“Both my parents are mixed, 50-50 black and white. Yes, I identify as black but I really don’t think I have the option. The truth is, we’re designated as things, we become categorized,” he said.

Troyli’s art is primarily about issues of race, stereotypes and otherness. He features himself in much of his work, connecting his personal story to his message. Troyli uses colorism in his work as a source of inspiration.

“I’m black, but in the black community I’m light-skinned which is an insult sometimes, and sometimes a compliment, you never know,” Troyli said.

He disagrees with the narrative that implies being light-skinned is negative.

“Anytime we’re making these blanket statements about a group of people based on the color of their skin we’re continuing these issues,” he said.

Although Troyli identifies as a black man, he acknowledges how others sometimes feel it’s more fluid.

“I exist simultaneously as black and mixed, I am both. In the eyes of the Western world, I’m a black man. In the eyes of the black world, I’m a mixed man. Never a white man.”

Ian Shelby is the lead Area Director for the nonprofit Progressive Abilities Support Services in Tampa Bay. Shelby recently visited a communication ethics class at USF St. Petersburg where he shared some life experiences and how they lead him to the work he does today, which is helping people with disabilities find meaningful work. Shelby considers that on a basic racial level, he is black and white, but he considers his ethnicity to be a relevant factor as well.

Ian Shelby is the lead Area Director for the nonprofit Progressive Abilities Support Services in Tampa Bay. Shelby recently visited a communication ethics class at USF St. Petersburg where he shared some life experiences and how they lead him to the work he does today, which is helping people with disabilities find meaningful work. Shelby considers that on a basic racial level, he is black and white, but he considers his ethnicity to be a relevant factor as well.

“Ethnically speaking my mother’s family is African-American, Seminole Native-American, Irish and German. My father’s side, the white side of the family … he still has some questions,” he said.

Shelby recognizes that race is a social interpretation but doesn’t downplay that on cultural levels it’s become a real issue. He grew up in a middle-class neighborhood surrounded by diverse families and friends who didn’t pressure him to define his identity.

“I wasn’t forced to choose, I was lucky enough to not have to. If I grew up in an African-American neighborhood perhaps I would’ve had to identify more, perhaps I would have been cultured differently,” Shelby said. “We’re all a product of our environment to a large degree.”

Shelby didn’t question issues of race until newcomers in his life began to ask questions.

“Later on, whether it was with girlfriends or newer friends they would almost be frustrated with my behavior. All of a sudden we’re talking about this one thing and it’s ‘you’re acting white, you’re switching out on me.’ That’s when the insecurities started,” Shelby said.

He recalls being asked “What are you?” as a teenager. “I answered it with ‘both.’ I don’t have to choose.”

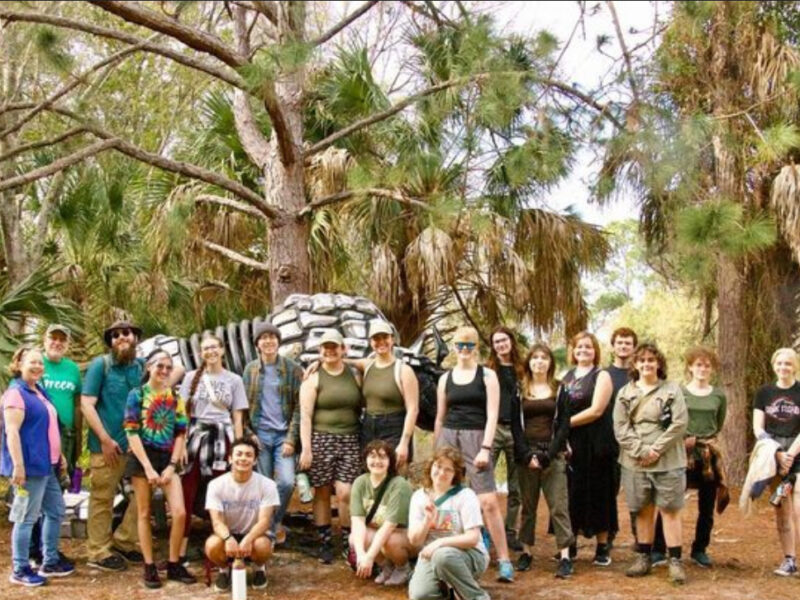

Photos by Martha Rhine | The Crow’s Nest

I love Jake’s quote. I have 3 biracial sons….and it is quite a responsibility to raise them in America today.