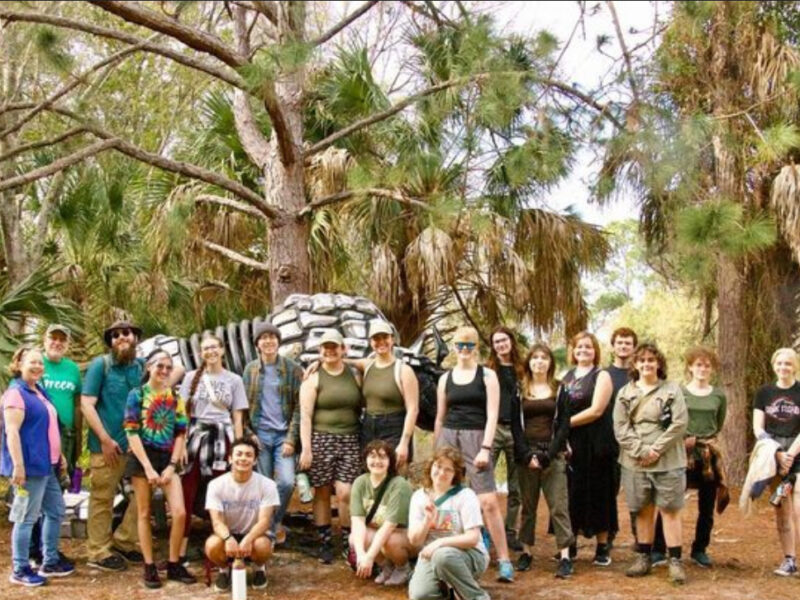

USF St. Petersburg senior Emma Guyette proudly lines up her homemade kombucha.

Courtesy of Emma Guyette

By Hope Weil

If you live in the St. Petersburg area, you’ve probably heard of the bubbly probiotic drink kombucha. The drink that was originally sold primarily in health stores can now be found at almost every local coffee shop and supermarket throughout the city.

While the drink is becoming more readily available commercially, it can also be brewed at home for cheap.

Kombucha (pronounced kôm-boo-cha) is typically fermented using either green or black tea. The fermentation process involves microorganisms, including an assortment of bacteria and yeast. While the drink is said to contain probiotics that help with digestion and provide additional health benefits, some scientists claim that there isn’t substantial evidence in the advantages of its consumption.

According to scientist Silvia Alejandra Villarreal Soto and his colleagues, kombucha’s biological properties are not well understood. In 2018, Villarreal and his colleagues conducted a study for the Journal of Food Science that found the microbiological composition of Kombucha is complex, and more research is needed in order to fully understand its behavior.

It’s an $800 million market in the U.S. and is expected to grow to $1.8 billion by 2020, according to Kombucha Brewers International, a Californian industry trade group.

The niche product has continued to thrive in a handful of urban cities, including St. Petersburg. A crowd favorite among the locals, Mother Kombucha was the first licensed commercial brewer in Florida. It celebrated its five-year anniversary last month. Owner Tonya Donati said she was a fan of the drink even before she founded “Mother.”

“I was drinking a lot of kombucha and I absolutely loved the way that it made me feel,” Donati said.

To Donati, kombucha is a better choice than soda, some juices and alcoholic drinks.

She stressed that it makes a great alternative to other habits that you may want to break, while still being more exciting than water.

Before Donati founded her company, she often brewed kombucha at home.

“It’s not magic, there’s a bit of science and art to it,” she said. “There is a saying: ‘If you can brew tea, you can make kombucha.’ It really isn’t that complicated, it’s a three or four step process and a little bit of patience.”

Donati isn’t alone. Many individuals find brewing kombucha at home to be pretty straightforward and equally rewarding. USF St. Petersburg senior Emma Guyette said she started making the probiotic tea at home because she found it to be much cheaper than purchasing it at the store.

“I’ve done a cost comparison, and it comes down to less than a dollar a bottle when you factor in all the ingredients and equipment,” Guyette said.

Bottles of kombucha typically go for $3 to $5, depending on the brand and the store.

Kathleen Gibson-Dee, a mathematics professor at USF St. Petersburg, is also a fan of brewing kombucha at home. Her daughter first introduced her to the process a few years ago.

“My daughter gave me my first symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast (SCOBY) and told me what to do, and I was like wow,” Gibson-Dee said. “It’s so easy. All you do is just let it sit there.”

SCOBY is thought to have originated in China. It is one of the four ingredients necessary for making kombucha tea. In addition to the SCOBY, you need tea, sugar and water.

According to Gibson-Dee, the first step in making kombucha is brewing the tea. She uses five tea bags to brew a half-gallon of tea. She then adds a cup of sugar into the tea and gives it roughly 30 to 45 minutes to steep.

“I use organic sugar because that’s just me. If the point is to be healthy, be healthy,” she said.

After waiting for the tea to cool to about room temperature, Gibson-Dee pours it into a jar, adds a half-gallon of water and then adds the SCOBY.

“They look like jellyfish, they feel like jellyfish,” she said. “It is thousands of little living creatures and people get grossed out, but I think the SCOBY is like an entire universe of living beings and you just let them live there.”

The SCOBY spends roughly two weeks eating the sugar inside the tea. If you want a sweeter kombucha, you shouldn’t let the SCOBY ferment as long.

“You take care of your SCOBY. They give you kombucha, and it costs you nearly nothing,” Gibson-Dee said.

It should be noted that when SCOBY eat sugar, they produce alcohol.

“All kombucha has a little bit of alcohol in it,” Gibson-Dee said. “Generally, the sourer it is, the higher the alcohol content.”

While most bottles will not contain enough alcohol to be branded as an alcoholic beverage, consumers should still be cautious when brewing the drink at home.

If you want to track the alcohol content of your kombucha, you can invest in a hydrometer, which tests for alcohol and sugar levels. The device is easy to use and relatively inexpensive, ranging from $10 to 30, depending on which one you get.

After the process is complete, Gibson-Dee bottles her kombucha and puts the bottles in her cupboards until she gets around to drinking it.

“It’s perfect after work, have a nice little kombucha and watch the sunset,” she said.

If you are interested in brewing your own kombucha but want some extra guidance, Mother Kombucha offers a class to get you started. The two-hour session is an introduction to the art and science of kombucha, explaining the history, background and science of the drink. The price of the classes varies from free to $20, depending on the host.

“The class gives you a solid understanding to brew, what to look for, and gives you tips at the end about if you want to use alternative items for different types of teas and flavorings,” Donati said.

For additional information about Mother Kombucha’s workshops, visit https://motherkombucha.com/about/ or call 727-767-0408.

It is no wonder you all feel wonderful – even the big manufacturers of the stuff can get to nearly 5% ABV. With only 12-26% typical real degree of fermentation they is room for a lot more alcohol and carbon dioxide to be produced. Storing in sealed bottles in a cupboard means asking for trouble. Last year we were involved in a legal case where a woman after having resealed a bottle with partial fill remaining nearly lost her eye in the ensuing explosion. And our lab still has chia seeds embedded in the ceiling from some that exploded here about 8 years ago. Also thanks to the aforementioned KBI (in your article) a hydrometer could well be next to useless to measure the alcohol content and there is more to extract than sugar. An if you are selling the stuff, a hydrometer is not officially approved by regulatory authorities nor by the KBI, who claim to have your interests in mind. Tread carefully if using the “magic mushroom”. There is a reason I think it should be called Komboomcha!