The Freedom Riders was a movement that forced national attention on civil rights in 1961 by testing federal interstate travel integration laws in the South. The riders were beaten, bombed and thrown in jail for trying to integrate interstates and bus stations.

This summer, a group of 40 students and teachers from USF St. Petersburg, Stetson University College of Law and Stetson University, Deland, set off for a week on a bus into the heart of the South to learn their story. The itinerary was aggressive—seven days of nearly non-stop touring and lecturing on the Freedom Rides, the civil rights movement and what came after.

USFSP’s group was a mixed bag of graduate Florida studies students and various undergrads. Our fearless leader, historian and USFSP professor Ray Arsenault’s book “Freedom Riders” was made into a PBS American Experience documentary last year. It gained national attention after “The Oprah Show” invited Arsenault and all living Freedom Riders to come on May 4 for the 50th anniversary of the Freedom Rides.

We started in Nashville, where the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee originated. In downtown Nashville, SNCC orchestrated sit-ins at segregated lunch counters, stand-ins at the segregated movie theatre and eventually participated in the Freedom Rides. They were taunted, beaten and jailed. We traveled with Rip Patton, one of the 14 students from Tennessee State University who were expelled for participating in the Freedom Rides.

The Freedom Rides began long before 1961, but the movement that spurred the most attention began with a group of students in Nashville, Tenn. Nashville’s Student Non-Violent Coordinating Council was composed of mostly Tennessee State University and Fisk University students.

Their efforts wouldn’t have been possible without the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). CORE’s Jim Lawson was an avid civil rights activist who instilled students with the understanding of Gandhian nonviolence, Jesus Christ and Martin Luther King Jr.

In Nashville, SNCC students who trained through CORE began sit-ins to integrate local businesses. Students were instructed how to cover themselves when attacked. They couldn’t talk or joke or laugh. They were instructed to be stoic and steadfast. If the police came, you didn’t fight back, you simply got arrested and either posted bail or spent the night in jail.

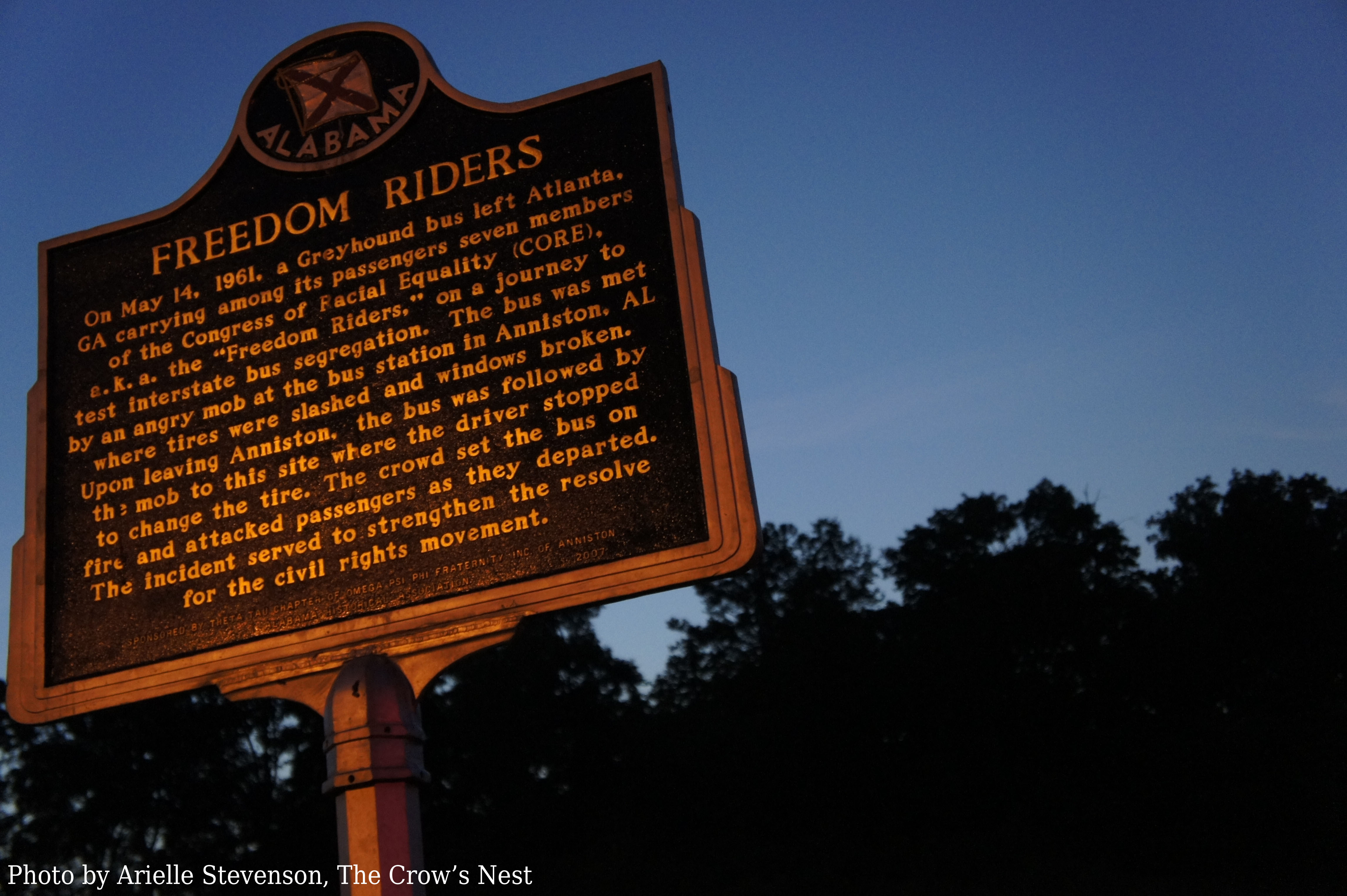

CORE organized the first Freedom Ride in 1961 from May 4 to May 17. That ride included some Nashville students. Local Ku Klux Klan members attacked them in Anniston, Birmingham and Montgomery, with help from local and state police. After the attacks, students in Nashville decided the rides had to continue. Over the coming weeks, Nashville’s SNCC inspired 436 students from across the country to board buses to integrate the interstate buses and bus stations.

But walking through Nashville after dark, the historic civil rights narrative was replaced with country music fare. There aren’t any monuments on the streets of Nashville to commemorate the incredible amount of work and change that happened there. Walking through the streets covered in neon cowboy signs, you’d never know anything had happened here at all.

“You can’t see the bloodstains anymore,” said John Seiganthaler, journalist and former aide to Robert Kennedy. He was knocked unconscious by an angry mob attacking the Freedom Riders in Montgomery.

For the Freedom Riders who still reside in Nashville, it hurts. Some had never even spoken about their participation until a few years ago.

“I didn’t tell my husband until eight or nine years ago,” said Patricia Armstrong, one of the Nashville-based Freedom Riders. “I think part of me was ashamed and part of me feared retaliation.”

A plaque on the side of the road marks the Freedom Riders who were mobbed in Anniston’s Greyhound station, tires slashed and later bombed down the road. The doors marked “colored” have been boarded up but are still visible.

In Birmingham we witnessed utter poverty in an area dubbed Dynamite Hill because of the incredible number of racially charged bombings that occurred there. We watched the landscape of Jim Crow and its fallout from the view in our air-conditioned tour bus. We passed neighborhoods and communities destroyed by what happened 50 years ago.

In Nashville, Memphis, Birmingham, Montgomery, Anniston, Selma and Atlanta, we met people who were doing anything and everything to preserve civil rights. Most had little funding to preserve or maintain these places, coupled with the recession and strong discrimination from those wanting to forget an ugly past. We learned about each other. We learned about our own prejudices and those we face everyday.

We met Federal Judge Myron Thompson in Montgomery. Thomson was the first African American employee for the state of Alabama who wasn’t a janitor or teacher. Thompson presided over some of the most controversial and notable decisions of our time, including the removal of the Ten Commandments from the rotunda of the Alabama state judicial building. He spoke about what it takes to be a good judge.

“Empathy,” Thompson said. “You have to understand the plight of people who are like you, who are the total opposite of you and still be unbiased towards them.”

He worked under Justice Johnson, one of the key justices in the crafting Brown v. Board of Education decision. Justice Johnson ruled on gay rights, equality for women and prisoner’s rights in a time when it would seem too progressive to do so.

“We all have a little racism, a little sexism that comes from an unconscious place where we want to make a quick decision about who we feel comfortable around,” Thompson said. “You have to come to grips with your inner self and not get set in your ways and always be open to new ideas.”

Shortly after our return home, the documentary based on Arsenault’s book was nominated in three categories for the Primetime Emmy Awards; Exceptional Merit in Nonfiction Filmmaking, Outstanding Writing for Nonfiction Programming and Outstanding Picture Editing for Nonfiction Programming. The awards are announced in September.