In the classroom, professor Hugh LaFollette’s teaching style is open and conversational. He often leans back in his chair, sipping from a clay mug as he expounds on ethics, philosophy and politics in a warm Tennessee accent.

Students sit around the room in a circular fashion, and raise a question whenever they have one. It is a democracy that he encourages.

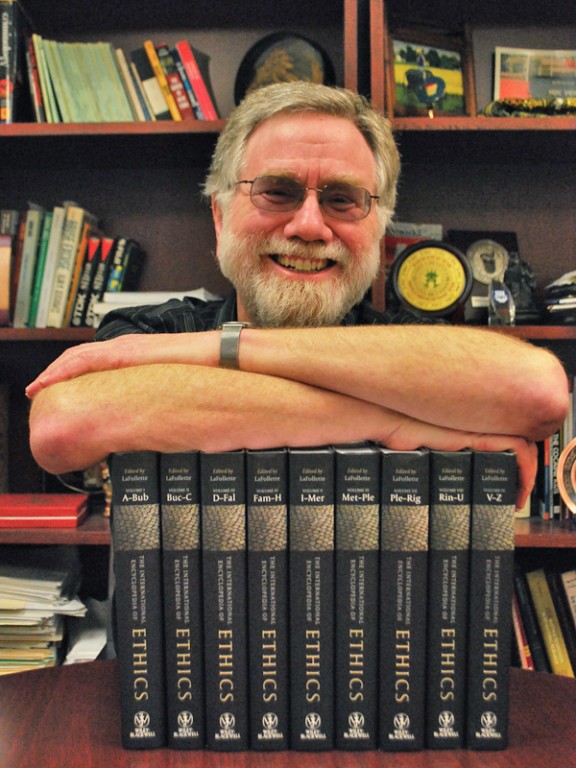

LaFollette is an accomplished writer, editor and renowned ethicist who recently headed production and editing for a definitive, nine volume encyclopedia on ethics. But someone observing his class or striking a conversation with him wouldn’t know any of that.

Instead, he talks about his family, the mountains of Tennessee and his favorite films. Most of all, he talks about the rewards and struggles of teaching for 40 years.

The path that brought him to teach in Florida was much by chance — something LaFollette feels more people should be open to.

“As it turns out, I think much of life is a quirk,” LaFollette said. “You can completely over-plan your life. If you have detailed plans, you can end up closing off options.”

LaFollette, 65, was born and raised in Nashville. He said he didn’t do particularly well in school, and he was never exactly sure what he wanted to do with himself. He graduated from Belmont University (then Belmont College) in 1970 with a degree in psychology.

He then applied for a job at the local newspaper, the Tennessean, on a whim.

“I thought it sounded fun at the time,” LaFollette said.

After six months of pestering, he was hired as a general assignment reporter, and soon got promoted to metro reporter, covering city politics. He enjoyed it but kept encountering situations on the job that troubled him.

While working, a Vanderbilt professor noted LaFollette had a philosophical streak.

“Journalism was why I went into philosophy. I was dealing with increasing ethical dilemmas at work and not knowing what to do about them,” LaFollette said.

He decided to take a leave of absence from the paper to enroll in some ethics courses at Vanderbilt. He hadn’t planned to get a degree, but he found he had a passion for the subject, and decided to quit reporting all together.

His replacement at the paper happened to be a young Al Gore.

“The last two weeks I was there, I took him around to meet all the people in city hall,” LaFollette said.

LaFollette earned a masters and doctorate in political philosophy at Vanderbilt, but he said it was intimidating at first. Vanderbilt didn’t have anybody who specialized in ethics at the time, so he carved out a committee of people he thought were “smart and good critics.” Then he had to rush through getting his Ph.D. because money was tight. He also felt disadvantaged compared to his peers, who had gone to better schools and had prior experience with philosophy.

After a year and a half in the program, the university offered him a teaching assistantship.

LaFollette then taught three courses a term while also finishing his degree. Teaching was not only not as intimidating as he thought it would be, but he found he loved it, and he said it soon became a part of his identity.

After finishing his Ph.D., LaFollette took a visiting professor job at University of Alabama-Birmingham for one year before accepting a position at the East Tennessee State University. He was happy to return to the mountains.

The only downside to teaching, LaFollette said, was the thought of having to publish his own work.

“I was getting into the profession at about the time that you had to publish if you were going to make it. At first I didn’t see myself as publishing at all, and then I saw myself publishing simply because I had to.”

After a time, though, he said he began to develop a passion for writing, and a greater love of the revising process. Now his career work includes a long list of books, journal articles, contributions and editing on numerous publications.

Despite this success, writing has always remained a secondary passion.

“For only a handful of people in the field at any time will it be true that their influence is more profound by what they wrote than what they taught,” LaFollette said. “For almost every one of us, the biggest difference we’re ever going make is if we make a difference in the classroom. When I look back over my entire career, there were about six teachers who made me what I am. If in a year I can influence one student anything like those people influenced me, I’ll consider my career a smashing success.”

LaFollette said he tries to use the challenges of teaching to improve himself, but it can be frustrating.

“When I get students who are surly or mad at me, part of me gets upset, but part of me questions myself. If I think I did a bad job in a class, I’m in a sour mood for two days. The joy of teaching is feeling as if you make a difference. The pain is having students who seem to despise what you do.”

The redemption comes in the form of those students that he has made a difference for.

“I’ve had students who have written me 20 years later about an experience in my class. All of a sudden, all of my complaints about what’s going on vanish, and I think, ‘Maybe I am doing okay.’”

During his time at UET, LaFollette had the opportunity to teach in Scotland for two years, so he took his whole family with him. He and his wife, Eva, still return whenever they can.

“One of these days, if I don’t kick over first, I’m inclined to write a book called ‘Confessions of a Scotaholic,’” LaFollette said. “The people, the climate, the land # it’s so diverse. And I never met an illiterate Scott.”

LaFollette said teaching at a Scottish university was very different and interesting, but he missed American students’ penchant for asking questions and challenging authority.

In 2004, LaFollette was preparing to take a job in Michigan when the offer was suddenly withdrawn due to financial trouble. He heard about an opening for the Marie and Leslie E. Cole Chair in Ethics at USF St. Petersburg. He didn’t know what to expect, but when he flew down for the interview, he was quickly attracted to the job by the diverse faculty and the city of St. Petersburg itself.

LaFollette said St. Petersburg is the only place in Florida he would consider living, both for the climate and the “small town feel with large town amenities.”

At USFSP, he teaches upper-level philosophy and ethics classes as well as Honors College courses, and is known for being a tough grader. He said he strives to make his classes “as sufficiently rigorous, demanding and thought-provoking as you would get at a higher profile university.”

Despite his credentials, he despises titles and seeks to make his classroom as democratic as possible.

“I’m old. I could be almost every student’s grandfather or great-grandfather. But I’m also not good at being an authority figure, where you pronounce your authority. I think if you deserve respect it’s because you do things that merit respect, not because you have letters after your name. Being called doctor makes me cringe, personally,” LaFollette said.

During his third year at USFSP, LaFollette was approached by the publisher Wiley-Blackwell to produce an encyclopedia on ethics and took on what would become a monstrous project.

In the end, he accepted 700 entries from 600 authors from around the world. The result was a nine volume work that LaFollette said he hopes will be the standard of the field for the indefinite future. The online version will be updated and amended every year.

“The farther away it gets the less painful the memories are,” LaFollette said, laughing.

His newest project is a book called “The Ethics of Gun Control” that he has decided to take public input on — a chance that readers don’t usually get. Once a month, he will hold meetings at the university inviting students, faculty and members of the general public to come and offer their insights on the controversial topic. The first meeting was held on Thursday, Nov. 21, at the Dali Museum. LaFollette said he was happy with the turnout, but he would like to see more young people.

As for the future, LaFollette said, “I could in principle retire, but I feel like my brain hasn’t atrophied quite yet.”

His pastimes include spending time with family and watching movies (his all-time favorite is “Lawrence of Arabia”). He also keeps an eye out for the rare occasion when the Ale and the Witch gets his favorite beer, Smutty Nose Robust Porter, on tap.

“You can still taste it three hours after you drink it, in a good way,” LaFollete said.

life@crowsneststpete.com