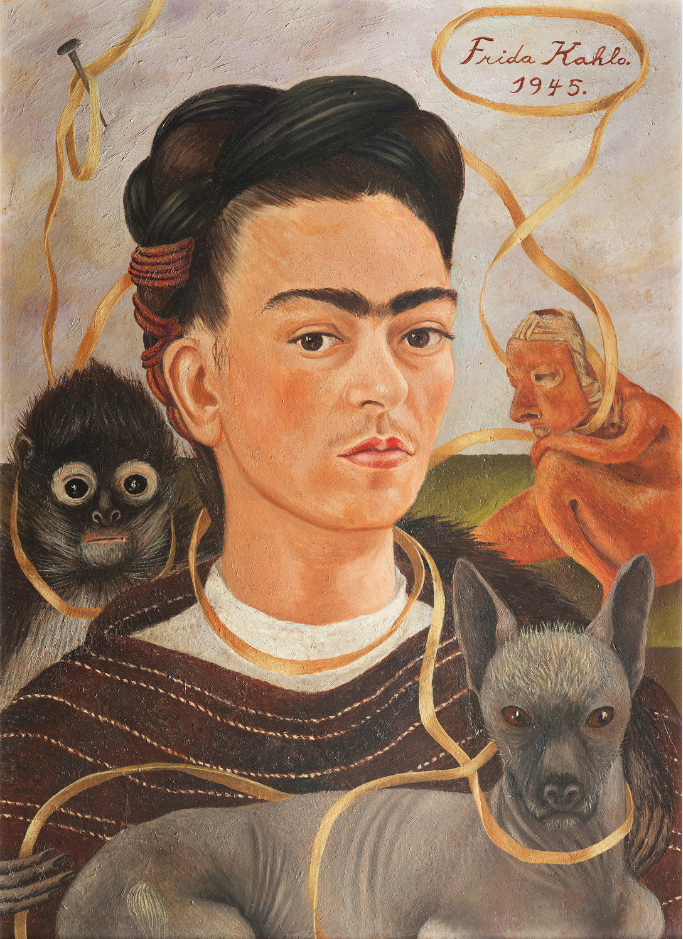

Frida Kahlo’s self-portraits blend magical symbolism with emotional defiance. Her stern features unapologetically tell of the inner turmoil and pain she suffered throughout her life. A pain that, in some paintings, manifests as symbols ranging from animals to shapeless masses that both torture and comfort her.

André Breton, a French writer, poet and the founder of surrealism, once described Kahlo’s work as a ribbon tied around a bomb.

“The Great Collection of Frida” will open at the Salvador Dalí Museum on Saturday, Dec. 17 and run through April 17. The exhibit was curated in part by the Dalí and the Museo Dolores Olmedo in Mexico City. Utilizing her paintings, drawings, personal photographs, the exhibit hopes to tell the story of her troubled life.

The exhibition also expands to the garden behind the museum with a number of plants and sculptures that resemble the artist’s own garden outside her home Casa Azul (Blue Home.)

“Dreams of Dalí,” an interactive VR experience that allows users to enter Dalí’s famous painting Archaeological Reminiscence of Millet’s “Angelus,” has been reintroduced to the public, as well.

Kahlo, born in Mexico City in 1907, has been internationally celebrated as representative of the Mexican and indigenous tradition. She is respected as a great feminist artist for her vivid and uncompromising vision of the female form and experience.

Like Dalí, Kahlo’s look is iconic with her uni-brow and hairline mustache, she often paints herself looking defiantly into the viewer, or weeping.

Dr. Hank Hine, co-curator and executive director of the Dalí, said that two Kahlo’s can be seen throughout her work. At the age of 18, Kahlo was in a bus accident that left her bedridden and near death. A handrail entered through her left side and exited near her genitals. The doctors expected her to die.

She survived and began painting while still recovering. This accident took her ability to bear children. Kahlo suffered a number of health problems throughout the rest of her life. This sick and weak form stood in stark contrast with the vibrancy of the artist within her, Hine said.

Hine also pointed out an important similarity between Dalí and Kahlo: their love lives. Frida Kahlo’s muse, Diego Rivera was another revered Mexican artist. Their love was tumultuous and difficult, much like Dalí and Gala’s love.

“They were both moved by romantic love, but as we know, romantic love often fails,” Hine said. “They almost mythologized the other person, so that person who was the object of their love could make mistakes, could be a bad partner but they were still this kind of lodestar by which they found their bearing.”

Rivera slept with a number of women, even Kahlo’s younger sister at one point, yet the artist could not waiver in her admiration for her muse. She depicts him as a monkey, which they kept as pets, in her famous work Autoretrato con changuito (Self-Portrait with Small Monkey).

Kahlo died in 1954, but her artwork has traveled across the world. Now it finds itself in the city of St. Petersburg. The Dalí Museum is free for USF St. Petersburg students.