By Timothy Fanning & Dinorah Prevost

The new University Student Center was opening five years ago when The Crow’s Nest began publishing stories that raised questions about the way the facility was being financed.

The reaction of university administrators was quick and fierce.

Editors Christopher Guinn and Ren LaForme went to the Tampa campus expecting to conduct follow-up interviews on the financing issue.

But when they got there, they said, they found themselves surrounded by half a dozen college officials who heatedly took issue with their reporting and lectured them on the difference between fact and opinion.

“In that conversation, we pushed back and said we would keep doing it because we think there is something here,” said LaForme, who is now the digital tools reporter for the Poynter Institute, a school for journalists in St. Petersburg. “But having two people in their 20s, sitting at a conference table at the top of a building in Tampa with administrators around us, it was very much an intimidation tactic.”

That scene – student journalists butting heads with college administrators – has played out repeatedly on American college campuses in recent years.

At some schools, student editors have found their budgets cut, their public records requests ignored or their advisers fired, or all three, and some disputes have ended up in court.

In recent months, the debate has returned to USF St. Petersburg.

At issue is a proposal to put The Crow’s Nest, which is largely independent, under the control of the Department of Journalism and Digital Communication.

That approach was raised by top university administrators and Student Government President David Thompson, who say it might improve the paper and enhance educational opportunities for journalism students.

But the journalism department doesn’t want that responsibility, according to its chair, Deni Elliott, and journalism professors agree it is best to leave the paper under the control of student editors.

Several former Crow’s Nest editors-in-chief also oppose the proposal, which they fear is a ploy to try to rein in skeptical, sometimes unflattering, coverage of the university administration and Student Government.

“The paper has always been and was always meant to be a place where students can publish things to other students,” said Devin Rodriguez, editor-in-chief in 2016 – 2017. “This is a place for students to grow, a place for students to speak unhindered, and any movement by faculty or administrators to put more nets or obstacles in that path goes against what a student newspaper stands for.”

“I think there’s a hell of an advantage to being thrown in the position to have to run this thing,” said Guinn, now a city government reporter for The Ledger in Lakeland. “I mean you can’t not have a newspaper, so you have to put something in it every week, and being responsible for that really sharpens the senses in ways that are so significant to your career later.”

Articles were ‘untimely’

The Crow’s Nest now comes under the university administration’s office of Student Life and Engagement, which is the umbrella over Student Government, the Harborside Activities Board, the Office of Multicultural Affairs, and Campus Recreation department.

The newspaper’s annual budget, which this year is $48,387, comes out of students’ activities and service fees and is set each year by Student Government. The newspaper has an adviser —an adjunct instructor and former editor at the Tampa Bay Times— but student editors make the final decisions.

Talk of a new home for the paper began last spring, according to Martin Tadlock, the regional vice chancellor of academic affairs.

He said Regional Chancellor Sophia Wisniewska asked him to inquire about various models of collegiate journalism and how the journalism faculty here interacts with the student newspaper.

“We were looking at academic planning all of last year. We have new initiatives rolling out over the next five years, and this was just one of those inquiries I was making about how things work here at USFSP,” said Tadlock, who became vice chancellor of academic affairs in July 2016.

These inquiries came after the newspaper published articles that the university felt were untimely, he said.

“There were some concerns about a couple of the stories that were published in The Crow’s Nest. One was about (Arts and Sciences) Dean Frank Biafora near the end of the search process with St. Pete College, and that story came out when he was a finalist for the (president’s) position,” said Tadlock.

“The search was still underway, which is a very sensitive time to have an article of the dean over here who is a finalist for the position over there.”

(The Crow’s Nest story was published April 17 – seven days after St. Petersburg College announced the names of the five finalists for its presidency and six days after a story about it appeared in the Tampa Bay Times.)

“There was another story about a staff member who had left the university at the same time that individual was applying for a position somewhere else,” said Tadlock. “And the time again had a very negative impact on that person’s ability to get a job somewhere else.”

Tadlock said he could not recall the name of the staff member.

“The timing of those two stories definitely contributed to me being asked about The Crow’s Nest, how it’s organized and how it functions,” said Tadlock. “I answer to (Wisniewska), so when she asks me a question about any area in academic affairs I go and find out and get answers to help educate her.”

Wisniewska told The Crow’s Nest that administrators are looking for the best possible structure for the student newspaper.

“We’re looking at providing the most sensible and most educationally beneficial structure for the student writers,” said Wisniewska, who added that some students have complained to her about the paper. “We’re having conversations with the guidance of the journalism faculty but have not made decisions, as far as I know.”

Thompson, the Student Government president, said he brought concerns to Tadlock over the summer.

Thompson said he wanted to ensure the newspaper has better academic support and to avoid potential conflicts of interest between Student Government, which funds the newspaper, and the paper, which covers Student Government.

“This is a place for students to grow, a place for students to speak unhindered, and any movement by faculty or administrators to put more nets or obstacles in that path goes against what a student newspaper stands for.”

In 2016-2017, the newspaper’s budget was $50,155. Last spring, the student Senate – citing a looming decline in revenue from student activities fees – tentatively cut the paper’s budget for 2017-2018 to $42,648 while increasing the budgets for several other campus organizations.

After editors protested, the Senate raised the budget to $45,648. A Senate leader said the paper’s sometimes skeptical coverage of Student Government did not figure in the budget deliberations.

Referring to that episode, Thompson said he wanted to ensure that The Crow’s Nest is protected from any form of malpractice or abuse of power in the future.

“We were also thinking that the (journalism) department has people in the journalism field who can assist and provide and potentially make contributing to The Crow’s Nest a mandatory part of the Journalism and Digital Communication degree,” Thompson said.

A ‘boutique department’

Frank LoMonte is a journalist-turned-lawyer who for nearly a decade was executive director of the Student Press Law Center, a Washington-based nonprofit organization dedicated to educating and defending high school and college journalists.

LoMonte, who is now director of the Brechner Center for Freedom of Information at the University of Florida, said the model Thompson describes has worked fairly well on some campuses. But he warned that the paper’s content could become the journalism department’s de facto responsibility.

“It does open up a sense that people on the journalism faculty are being given that assignment because people (in administration) want to see them directly involving themselves in those editorial content decisions,” LoMonte said.

Elliott, the chair of the journalism department, told The Crow’s Nest the department does not want that responsibility.

“I think there are some colleges and universities that have really good journalism departments that do collegiate journalism. We are not one of them,” said Elliott. “We’re a very small, boutique department. There are some things we do extraordinarily well, and I don’t think that our journalism faculty would be interested in picking up collegiate journalism as an area of focus.”

In a meeting Friday, the journalism faculty agreed with Elliott.

Members of the administration have complained to them about The Crow’s Nest coverage, journalism professors said, but it is best to leave the publication in the hands of student editors who are learning the craft.

“Our university does a fabulous job of doing open meetings and being transparent in its operations,” Elliott said in an interview. “But at the same time it’s kind of like a philosophical question of how does a community like the university function well when it’s being scrutinized by people within the community?

“I would argue that is an important role for any university that is all about preparing students to be active citizens in a democracy,” she said. “The best practice we can give students in journalism or any other field is to help them learn how to think critically about the environment in which they find themselves.”

Elliott said she will seek to arrange “educational opportunities for the entire college community” – including top administrators – on the role of the student press on campus.

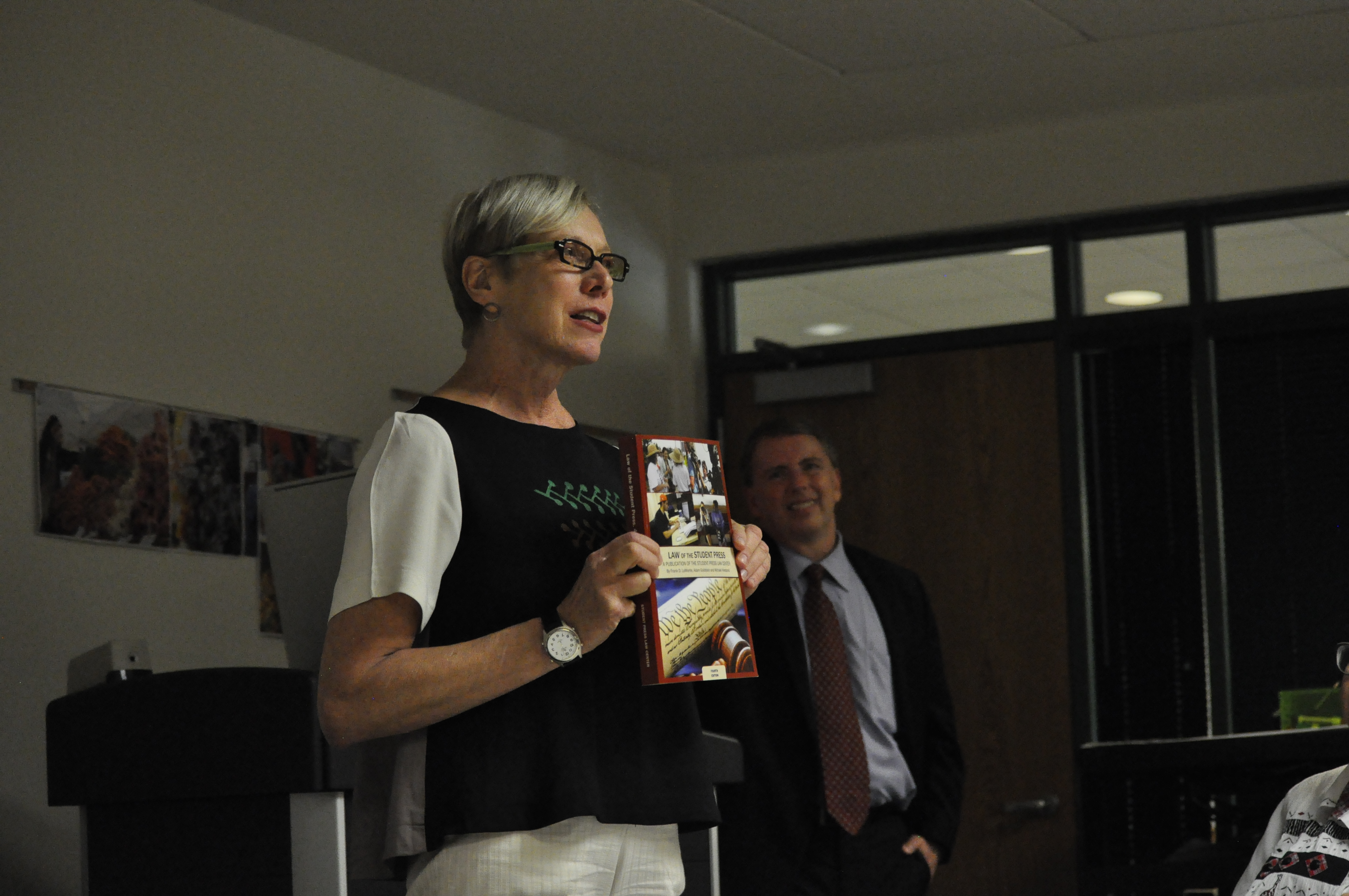

The first opportunity came Aug. 14, when LoMonte came to campus at Elliott’s invitation to speak about the role and responsibilities of student journalists.

His talk attracted more than three dozen people, including five former Crow’s Nest editors-in-chief and most of the current staff and journalism faculty. Wisniewska and Tadlock both put in brief appearances.

LoMonte spoke to the problems that college newspapers face when housed under a journalism department – as proposed here – or a school’s student life department, where The Crow’s Nest is now.

LoMonte said one of the benefits of putting student media under student life is that it establishes journalism as more of an extracurricular activity.

“I think that journalism should not be regarded as an academic activity because then you get academics, well intentioned or not, trying to micromanage the paper,” LoMonte said.

The College Media Association, a collegiate media advocacy group, frowns on advisers who require student reporters to submit their work to them before publication, LoMonte said.

Instead, advisers should have an open door policy, where students can bring drafts of articles to be looked over and edited before publication.

“It’s only when the adviser says, ‘I’m going to take the ‘run-or-don’t-run’ decision’ out of the hands of the student editors,” said LoMonte.

“That runs a bit of risk of blurring that otherwise clear line of non-responsibility on the part of the institution. Keeping that relationship truly advisory in nature and not where the adviser wears the super editor or the super publisher hat is really the safest thing legally for everybody.”