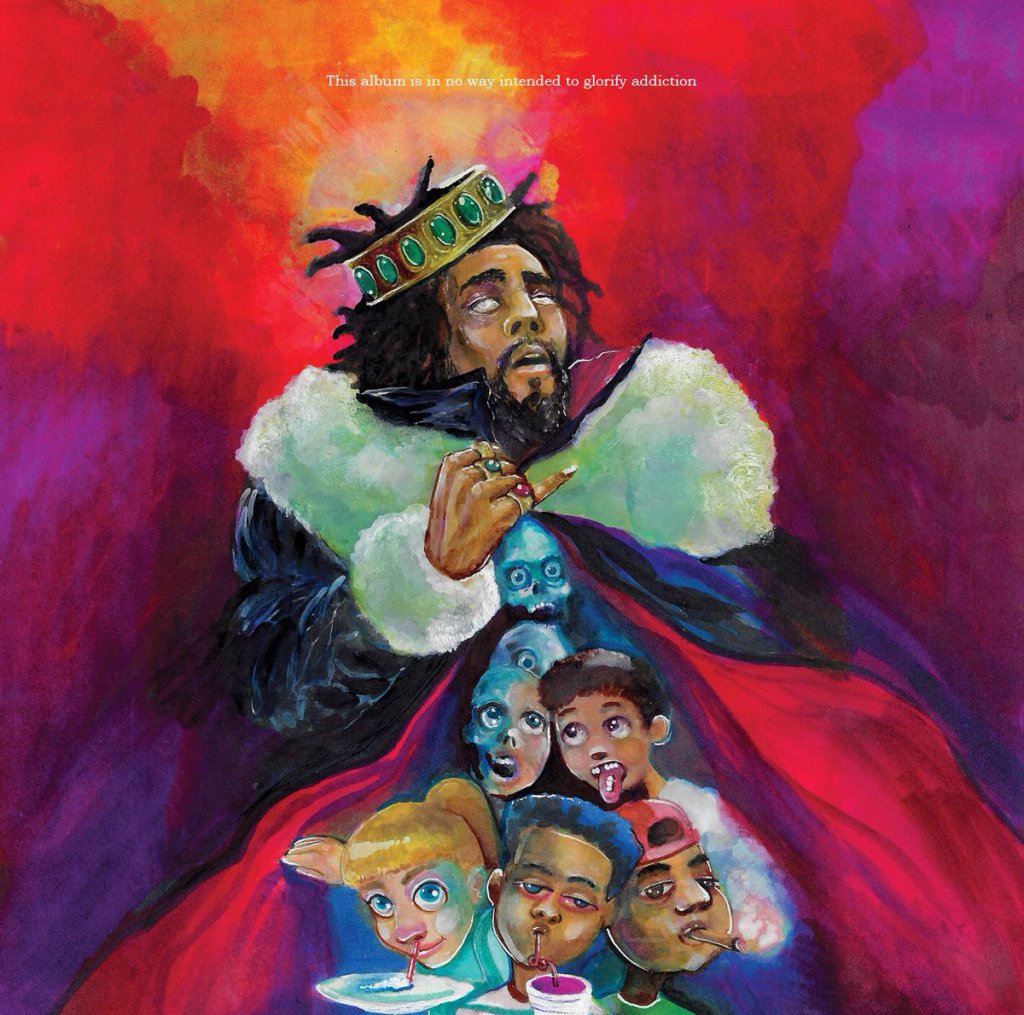

Above photo: In his most recent album, J. Cole’s steps out of his comfort zone and right into unabashed hypocrisy, relying on many of the musical tropes he criticizes. Courtesy of Interscope Records/Dreamville

By Jonah Hinebaugh

Whether you call it “Kids On Drugs,” “King OverDose” or “Kill Our Demons,” Jermaine Cole’s fifth studio album tackles all with a 45-minute commentary on the world around him.

Welcomed by some and hated by others, J. Cole has a seemingly compulsive need to attack the new culture and trend that has become ever-popular in today’s hip-hop scene. From his single “False Prophets” to present day, he has been preaching from a soapbox down to his peers.

This is what makes him divisive and listeners wary before playing this album.

Surprisingly, Cole, in some sort of shallow analysis of the current culture, borrows many aspects of what he criticizes. From repetitive choruses or the use of the triplet-style flow, it seems confusing as to why he thought this would be useful because it is far from his strong suit. (A prime example being the weak “skrrt” ad-libs on “Kevin’s Heart.”)

It does keep the listener awake, though — most of his albums put you to sleep before you reach the end.

The “mumble rap” style he uses seems like a lazy way to profit off something he disses. It could be a mockery of it, but it misses its target, and hopefully he won’t use it in any future projects.

On “Photograph,” Cole’s cliché qualities arise as he raps about how popular social media has become, specifically Instagram, as he falls in love with a girl solely on the pictures she posts. He talks about how he isn’t comfortable “shooting his shot,” so he tries to let her know his interest with a “click,” or liking her photo she posted.

This whole song will put off just about anyone who listens and is familiar with social media, but if listeners can make it through, he redeems himself. This song should be cut, and maybe he should download Tinder while he’s at it.

He produced every song on the album and again has no features besides an alter ego dubbed “kiLL Edward.” From beginning to end, it’s reminiscent of albums such as “To Pimp A Butterfly” and “DAMN.” by Kendrick Lamar. From whispering female vocals, pitched-down intros and bridges to mesmerizing beats that switch up at the drop of a dime, it reminds listeners of the talent Cole possesses when he channels it correctly.

Lamar’s influence on him is nothing out of the ordinary. Of all artists at the top of their game right now, these two resonate and share similar qualities compared to someone like Lil Pump, who Cole later disses on “1985 (Intro to “The Fall Off”).”

Just like in “DAMN.” J. Cole combines a ying-yang duality of love and lust with the baggage that comes with money, drugs and addiction. Some of his most important criticism comes toward the latter part of the album, with songs like “BRACKETS” and “FRIENDS.”

In the former, Cole denounces the absurdity and unsupervised handling of his taxes. He questions if it goes to schools that teach the heroism of white people without accounting for their sins? Or maybe some company that pours guns throughout the country to eventually “wind up in my hood, making bloody clothes”?

Welcome to the resistance, Comrade Cole.

“FRIENDS” describes the climate of the black community he is surrounded by. He explains the stigma surrounding mental health, leading to self-medication to cope with the pain repressed by individuals.

The message within the song sheds light on issues behind addiction, an issue that cripples communities, as well as the atmosphere surrounding predominantly black neighborhoods that have been oppressed through institutionalized racism.

Whether it be economics, an influx of drugs in the community or the prison industrial complex it creates, in his words, people who live there feel stuck and unable to attain anything more, and as a result, repeat the cycle for generations.

“FRIENDS” conveys raw emotion, showing how personal the issue is to him, which makes it the best song on the album. It is apparent all he wants for his friends, family and loved ones is success.

Another personal issue Cole brings to task is his mother’s alcoholism on “Once an Addict (Interlude).” Squeezed between the aforementioned tracks, he recounts avoiding the issue because he was too young to deal with the pain of “seein’ my hero on ground zero.”

The painful recollection couldn’t have been easy, but to anyone facing similar issues, it must help knowing that even people who are idolized don’t live perfect lives. The track seems to be a point of healing for him.

While some clichés are forced and unnecessary, he faces his demons in a deeply personal album he shares with the world. This album rarely loses its momentum, besides on songs like “Photograph.” While tying themes together is important, the album can be oversaturated, as he continually drives home similar points without saying anything new.

Avoiding dissing other artists and focusing on other issues that are more relevant to him would’ve made the album stronger. This is crucial because his final track is just a lame diss tarnishing a great run of emotive songs.

One of the most important aspects is to have a strong finish, but “1985 (Intro to “The Fall Off”)” ends the album on a sour note as he tries to overcompensate to prove he’s better than the younger artists on the scene.

It reinforces the stereotype, started by his “woke” fans, that people who listen to him have a higher IQ than those who like the trap-rap that is popular today, which is an elitist and corny viewpoint.

This album emulates his theme of dichotomy, whether it be his corny songs and great songs or the themes that arise within them. In any case, the album is worth checking out even if you aren’t a fan.