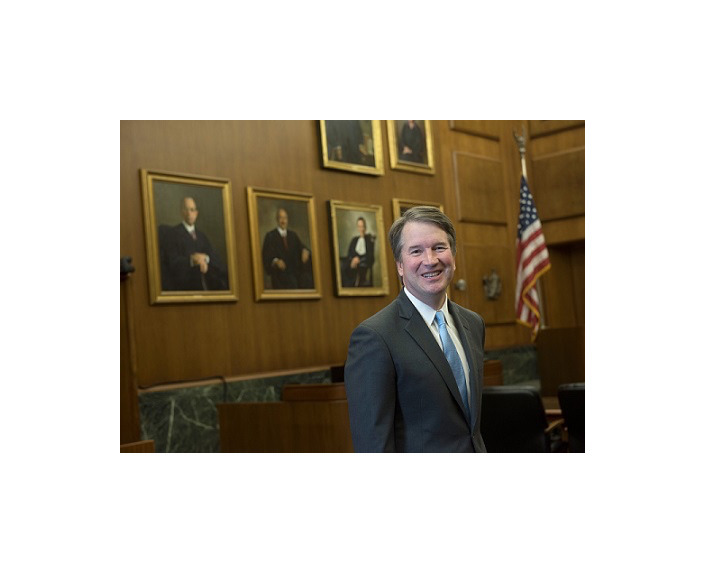

President Trump nominated Judge Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court on July 9. He was accused of assaulting Christine Blasey Ford 30 years ago. Courtesy of U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit

By Whitney Elfstrom

Should someone be held accountable for their alleged actions from 30 years ago?

This question often floats around journalism classes as a critical thinking test, but most recently the question has been applied to Supreme Court nominee Judge Brett Kavanaugh.

Kavanaugh was accused by Palo Alto University professor Christine Blasey Ford of sexually assaulting her at a house party when they were both teenagers. Ford said that Kavanaugh pinned her to a bed, put his hand over her mouth to muffle her screams, groped her and attempted to remove her clothes.

The Supreme Court nominee rebukes her claim.

Ford was able to get away before anything else happened, but so many others have been in the same situation and haven’t had the same luck.

Growing up, young women were taught how to go out of their way not to be assaulted. We’re told how to dress, how to act and how to “be careful.” For some reason, young men aren’t taught simply to not assault.

Even when met with all of the so-called “lessons” that women hear again and again, we can’t help what someone else will do. We’re not in control of other people’s actions.

The phrase “boys will be boys” or “locker room talk” have been shouted even louder than before since Donald Trump took office. Trump has been met with scandal after scandal, from his infamous recorded conversation with Billy Bush to his Stormy Daniels debacle.

Perhaps this is why some men don’t think they need to be held accountable for their actions.

In a tweet on Friday, Trump said, “I have no doubt that, if the attack on Dr. Ford was as bad as she says, charges would have been immediately filed with local Law Enforcement Authorities by either her or her loving parents.”

If the president of the United States has the audacity to point fingers and second guess an accusation before due diligence has been done, then it’s no wonder so many women have difficulty coming forward to report their assaulter.

Even with all of the lessons women are taught, whether it be how not to be assaulted or what to do if an assault does occur, far too often women have difficulty finding the strength to come forward because their assaulter took it away.

We’re afraid to come forward for fear of ridicule from the public — or our own communities, friends and family.

People have been asking, “Why now? Why, after 30 years, is Ford just now coming forward with this accusation?”

Thursday, Michael Barbaro reported on the New York Times “The Daily” podcast that after Ford and her family received death threats, they were forced to go into hiding.

All for standing up and reporting that a man, who is up for one of the most powerful positions in the U.S., may have assaulted her in her teenage years.

Now, journalists are not in the game of accusing anyone before conviction, but as Barbaro reported, even some of Kavanaugh’s friends have asked why Ford would have come forward if it wasn’t true.

When looking at situations like this one, people think it’s curious that these stories come to light right after a nomination or before an election. But here’s the thing: Some traumas stay hidden. We push them out of our heads, we try to forget that they happened and we distance ourselves from the event.

That is, until our attacker’s face is plastered across our television screen.

Kavanaugh’s actions need to be taken into account. By high school, we know the difference between right and wrong. We know the difference between yes and no.

Everything we do in life shapes who we become as adults.

If someone is capable of such horrific acts, shouldn’t we stop and think about this before they sit on the Supreme Court, one of the most powerful positions in the U.S. judicial system?

At its core, this is a systematic and societal issue. We should all be held accountable for our actions — no matter our age or gender.