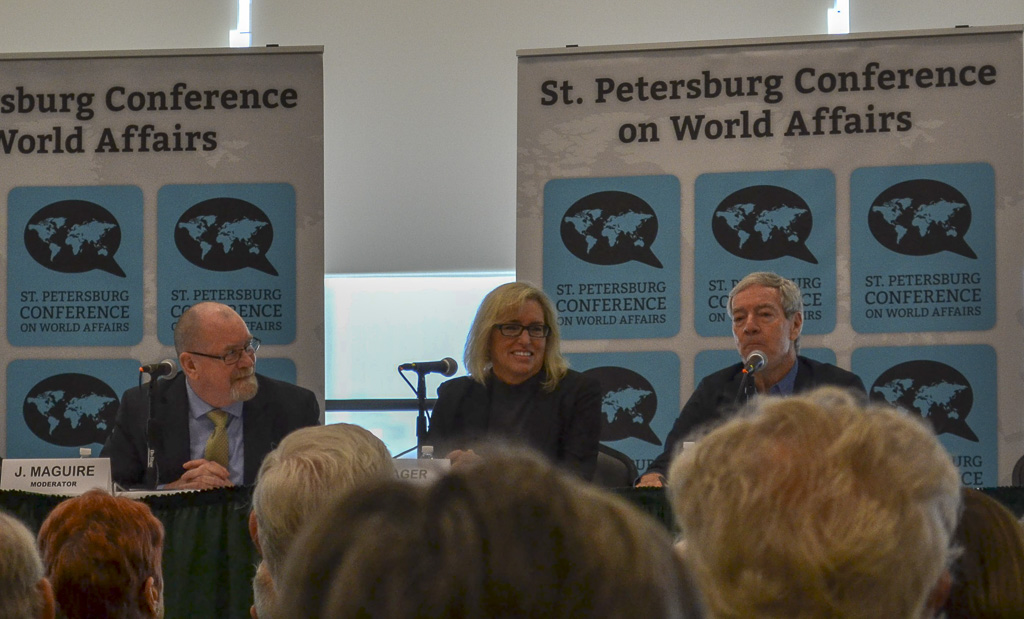

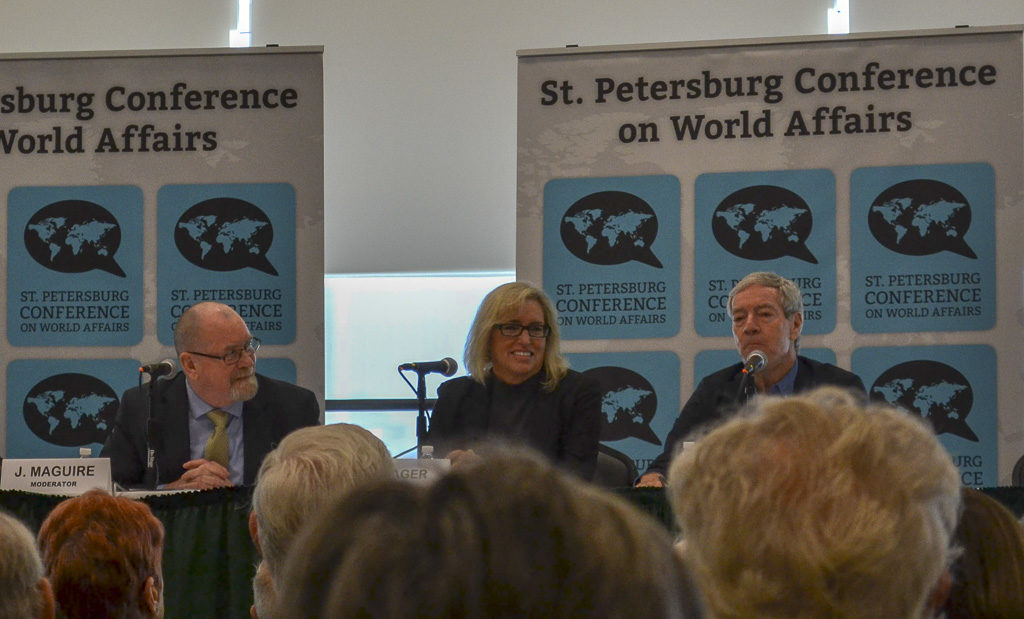

Most people don’t make a conscious decision to believe things that aren’t true, says Morrison. Amy Diaz | The Crow’s Nest

By Amy Diaz

The presidency of Donald Trump and proliferation of social media sites have injected two new terms into the national discourse about the news media:

“Fake news” and “alternative facts.”

Some people believe mainstream news outlets are biased; others blame the internet and rise of social media. Some put the responsibility on the reader to discern the truth; others might argue the truth is subjective.

A panel at the St. Petersburg Conference on World Affairs sought to get to the bottom of what happens when facts and beliefs collide.

While fellow panelists emphasized the importance of data and fact-checking, author, journalist and educator Donald Morrison argued that most people don’t make a conscious decision to believe things that aren’t true.

“As a journalist, I don’t think the problem is religion or politics,” said Morrison, a former editor at TIME magazine. “I think we are hardwired to look at the world and discern patterns and search for meaning. Once we think we (have) found that meaning, we invest a lot in it.”

Morrison cited experiments done in the 1960s by cognitive psychologist Peter Wason, who coined the term “confirmation bias” to describe people’s tendency to embrace information that supports their preconceptions and beliefs, even when the information is not true.

When given a series of three numbers, 2-4-6, participants in Wason’s experiments were asked to discern the pattern by presenting another series of three numbers following what they thought was the rule.

Wason’s rule was simply increasing the numbers. 3-4-5 would have followed the rule, but more than half of the participants came to other conclusions, deciding it had to do with even numbers or increments of two.

Once participants had their hypothesis, Morrison said, they stuck with it rather than testing other possibilities.

Morrison said this bias can be seen in the world of investing.

“If you’ve got a losing stock, you kind of stick with it hoping it’s going to turn around when you really should say, I’ve got to get out of this stock,” Morrison said.

“If I were in another line of business, I’d set up a hedge fund that took advantage of the human tendency to stick with a bad investment, because we’ve invested our own sense of self-worth and self-respect.”

Even as a journalism educator who encourages his students to step back from their work and look for alternative explanations, Morrison said, he himself is not immune to the impulse to confirm his own biases.

Last week, he said, a friend shared a story on Facebook that said Navy SEALs have been ordered to stop using camouflage on their faces in operations because it was considered blackface.

After researching the article and finding it on right-wing websites, Morrison said, he left a comment for his friend along the lines of: “How dare you post something like this? This is inflammatory. It’s been picked up by other websites. It’s poisoning the minds of America; this just can’t possibly be true!”

The article was satire.

Morrison encouraged the audience to check themselves for confirmation bias and take pride in being able to discern a new pattern rather than faulting themselves for being wrong.