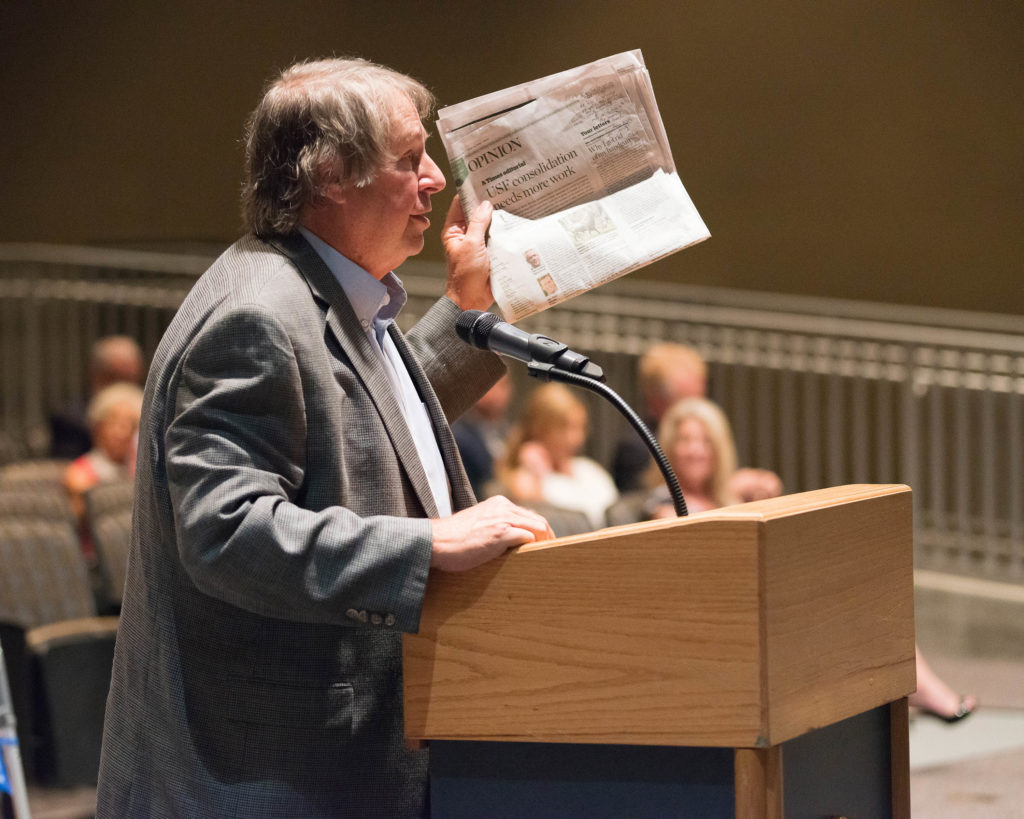

Faculty leader Ray Arsenault urged Pinellas County legislators to protect the St. Petersburg campus. Several lawmakers vowed to step up.

Courtesy of Chris Demmons, St. Petersburg College

By Nancy McCann

For weeks, the new president of the university system had stressed that consolidation would be a positive for the St. Petersburg campus, which he called “a gem and jewel.”

Then he dropped a bomb.

The “preliminary blueprint” he unveiled to the Board of Trustees and USF faculty, staff and students last week would move control of St. Petersburg’s academic and student affairs to Tampa, 35 miles and a long bridge away.

Currall stressed that his proposal was tentative, with room for big changes. But the deadline for submitting a draft of the document that will explain important details about consolidation to the regional accrediting agency is due to the university’s trustees on Nov. 1, just seven weeks away.

Stunned, many in St. Petersburg reacted with bewilderment and anger.

What happened to Currall’s pleasing promises on visits to the campus and community?

What happened to recommendations and reports from St. Petersburg faculty, administrators and staff during months of countless meetings?

What happened to the Legislature’s mandate that St. Petersburg and Sarasota-Manatee become full branch campuses with substantial authority over academics and student life?

“The way consolidation (planning) is going for us (St. Petersburg) is a disaster,” said Ray Arsenault, a professor since 1980 and president of the USF St. Petersburg Faculty Senate.

At week’s end, allies of the St. Petersburg campus began pushing back on Currall’s plan.

“As expected, a process fraught with secrecy and politics is not just about consolidating a university system, but consolidating power,” said St. Petersburg Mayor Rick Kriseman.

“USF St. Pete has always thrived in spite of the leadership in Tampa,” the mayor said. “As such, continued attempts to seize a beautiful, well-run academic institution in St. Pete will only result in the entire system’s decline.”

In an editorial, the Tampa Bay Times said the proposal “is awfully tilted toward the main campus in Tampa” and “neuters the regional chancellors” in St. Petersburg and Sarasota-Manatee.

The newspaper called on state Rep. Chris Sprowls, R-Palm Harbor, the powerful Pinellas legislator who championed consolidation legislation in 2018 and 2019, to step up.

Sprowls seemed to be listening.

At a meeting of Pinellas legislators on Thursday, he said “the Legislature has spoken on this issue” and expects the university system and Board of Trustees to follow both the letter and spirit of the law.

Sprowls’ colleague, Sen. Jeff Brandes, R-St. Petersburg, was more blunt.

“We are going to continue to support the great faculty and team at USF St. Petersburg and the regional chancellor to ensure the legislative intent is followed as relates to branch campus status,” he said.

As opposition to his plan grew, Currall issued a statement late Friday reiterating that the plan is tentative and evolving.

“The intent of this framework is to provide a perspective through which we will further develop our plans,” he said.

“As I continue with my ongoing listening tour visits, I welcome feedback and ideas from all of our stakeholders, including our faculty and students on all of our campuses, alumni, elected officials, accreditation leaders and members of our communities.

“USF’s impact stretches well beyond our campus walls, and as such it is our responsibility to ensure that our university is meeting the needs of all our communities and serves to elevate our region as a whole.”

Decades of domination

USF Tampa opened for classes in 1960 and the St. Petersburg campus five years later.

For years, the St. Petersburg campus was a tiny outpost along Bayboro Harbor dominated by administrators in Tampa.

Many professors and administrators in St. Petersburg chafed at that arrangement, and in 2000 a state senator named Don Sullivan mounted a push to sever the two campuses and make St. Petersburg a separate school called Suncoast University.

His effort fell short, but it prompted Tampa to cede more authority to St. Petersburg and led in 2006 to separate accreditation for USF St. Petersburg.

The freedom helped trigger growth in St. Petersburg’s numbers, prestige and swagger – a stretch that saw “an amazing surge of energy here,” said Arsenault, who joined the faculty in 1980.

Without warning, however, Sprowls and the Legislature sprang a plan in January 2018 to abolish the independent accreditations of St. Petersburg and Sarasota-Manatee and merge them with Tampa.

The Tampa campus had just become the third public university in Florida to be designated a “preeminent research university,” and Sprowls said he wanted to spread that prestige and extra funding to the smaller campuses.

Some senior faculty in St. Petersburg and their allies in Pinellas County government and business urged Sprowls and the Legislature to shelve or delay the consolidation plan.

They recalled the bad old days before separate accreditation and warned that Tampa would try to squash St. Petersburg once again.

Their pleas were largely ignored. But before the law was enacted in June 2018, Pinellas legislators added some safeguards for St. Petersburg.

The consolidation planning process would be led by a 17-member task force that would make recommendations on “specific degrees in programs of strategic significance, including health care, science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and other program priorities” to be offered in St. Petersburg and Sarasota-Manatee.

A pro-Tampa tilt

The task force held its first meeting in April 2018, but the administration of USF system President Judy Genshaft quickly took steps that controlled the planning process.

The task force became just one of several groups that hovered over a simmering stew of consolidation planning and recommendations.

First, the USF system administration hired Huron, a Chicago-based consulting firm that presented a lengthy report in September 2018 that outlined a consolidation strategy that favored USF Tampa.

Then the administration and trustees created a series of study groups to advise USF leadership – 86 professors, staff members and administrators – that met internally while the task force held a series of public meetings.

Those study groups – called the Consolidation Implementation Committee – were elevated by Genshaft and USF system Provost Ralph Wilcox to the status of the task force.

As deliberations – public and private – continued, a key issue emerged: Would St. Petersburg and Sarasota-Manatee become full branch campuses or instructional sites with little authority?

The CIC’s report in December 2018 included a “guiding principle” that referred to St. Petersburg and Sarasota-Manatee as “regional campuses,” a designation that was not explained.

But the task force recommended that the two smaller campuses become “branch campuses” as defined by the regional accrediting agency, the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACS).

That means the campuses would have their own administrative or supervisory organization and budgetary and hiring authority.

When the Board of Trustees adopted a consolidation plan and timeline in March 2019, it left the branch campus issue unresolved.

The plan also contains an unedited compilation – 530 pages marked “draft recommendations” – of the reports from 22 “teams and clusters” of faculty and administrators from the three campuses. The Genshaft administration hastily assembled these groups in early January.

In Tallahassee, Rep. Sprowls and his allies sided with the task force. In June, they pushed to passage a law that stipulates that St. Petersburg and Sarasota-Manatee will become full branch campuses as defined by SACS.

Enter Currall

When he was named USF system president, Currall inherited the hot potato of consolidation from Genshaft.

Since taking office on July 1, Currall has taken pains to assure the St. Petersburg campus and its allies in the community that the campus will prosper under consolidation.

When he met with editorial writers and reporters at the Tampa Bay Times last month, Currall said he has heard fears that St. Petersburg would lose its autonomy and identity, with many of its resources moving to Tampa.

“Those fears are not well-founded,” he told the Times. “I think a lot of that is just worrying.”

Then in a campus meeting on Aug. 30, Currall said St. Petersburg “has to be an integral part of the trajectory” toward the “world-class intellectual and academic footprint that we aspire (the consolidated) USF to have.”

Yet the “preliminary blueprint” for consolidation that he unveiled to the Board of Trustees on Sept. 10 sounded a lot like the documents and talking points that came from the Genshaft administration in the last months of her 19-year tenure.

Currall used words like “preeminence” and “Top 50” national university. He stressed the benefits that students and faculty on all three campuses would enjoy under consolidation and suggested that St. Petersburg might get several new “centers of excellence.”

But he also would wrest control of academic and student affairs from Tadlock and Sarasota-Manatee Chancellor Karen Holbrook and move these responsibilities to Tampa.

In an interview with The Crow’s Nest, Tadlock said that 75 to 80 percent of what he controls now in people, money and resources would go to Wilcox, the USF system provost in Tampa.

For years, all academic and non-academic divisions in St. Petersburg have reported to its regional chancellor. But Currall’s plan would whittle Tadlock’s responsibilities down to university “advancement” and oversight of the non-academic support staff.

Tadlock’s “refreshed” role under the plan includes acting as the president’s liaison with local businesses and the campus advisory board, identifying education and research needs of the community, leading emergency preparedness and managing fundraising and alumni relations staff on the campus.

“Right now, we get an entire campus budget directly allocated to this university (USFSP),” Tadlock told The Crow’s Nest. “Then we propose a budget plan to be approved by the trustees.

“We don’t know how the budget process will work in the future,” Tadlock said.

This diminished role of the regional chancellors does not seem to square with the duties of an executive running a branch campus.

Earlier this year, Belle Wheelan, the president of SACS, the accrediting agency that oversees colleges and universities in the Southeast, summed it up this way for a Crow’s Nest reporter:

A branch campus, she said, is a “full-blown operation with someone in charge.”

But is it legal?

Sprowls and other Pinellas legislators aren’t the only people who think Currall’s plan ignores state law.

Some of St. Petersburg’s longest serving professors think so, too.

In a statement sent to Currall on Aug. 29, 17 full professors and Patricia Pettijohn, associate librarian at the Nelson Poynter Memorial Library, said documents sent by Currall on July 23 on the proposed academic structure for consolidation do not match the requirements for a branch campus as outlined by the Legislature and SACS.

Branch campuses should have the authority to shape their budgets, hire faculty and tailor programs for their students, they said.

The proposed structure “seems Tampa-centric in ignoring not only the importance of local campus leadership, but the potential for locating central administration functions on campuses other than USF-Tampa,” the group told Currall.

Nancy Watkins, a member of the USF system Board of Trustees, brought another matter of law to Currall’s attention during last week’s meeting of the trustees in Tampa.

Currall presented an organizational chart showing the campus advisory boards of St. Petersburg and Sarasota-Manatee reporting to the president. The boards are composed of community leaders who help guide their campuses.

Watkins told Currall that the law says the campus boards report directly to the trustees. She was referring to Chapter 2018-4 of the Florida Statutes.

“My concern is that the Legislature has language . . . regarding the campus boards,” said Watkins. “What I don’t want to happen is that we do something in accordance with SACS that is not in accordance with the state statute.”

Currall said his chart is what SACS requires.

“We have SACS on one hand, and we have the state statute. Our commitment is to be in compliance with both; we are deeply committed to both,” he said. “We will not sacrifice the accreditation of this university. I just want to make that clear.”

Watkins repeated her concern.

“We’ve also got to not violate the law,” she said.