By Gabby Dacosta

Erin Symonds is a postdoctoral researcher who investigates water quality on the coast of Costa Rica.

Brian Barnes is a postdoctoral research associate who uses satellite data to measure the impact that dredging has on bodies of water.

Courtesy of Devin Firesinger

Patrick Schwing is a research associate who studies the way organisms on the ocean floor have responded to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico.

From the ocean floor of the Gulf to the beaches in Costa Rica, the three researchers at the USF College of Marine Science are looking for answers to an ocean of questions.

The USF College of Marine Science, which dates back 50 years, has 26 faculty members, a hundred graduate students and another hundred technical and administrative staff members.

The college is recognized internationally for its graduate education programs and research in ocean science. With scientists in every ocean, the college researches global and regional issues, including red tides, coral reef health, sea level rise and ocean acidification.

Collaborating with local, national and international partners, the college aims to increase and use knowledge of global ocean systems and human-ocean interactions through research, graduate education and community engagement.

“One of the misconceptions is that we know quite a bit about the global ocean,” said Schwing. “The truth is that we’ve mapped in high resolution about 3 percent of it.”

Since the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010, Schwing and the Center for Integrated Modeling and Analysis of Gulf Ecosystems, a research consortium of 19 U.S. and international partners, have been working on a 10-year program.

By collecting samples of sediment, water and fish tissue, they can measure at the impact and recovery of the Gulf ecosystem.

He explained some of the results of the project.

“We are getting a pretty good idea of what type of impacts to expect from a large submarine oil spill and what sort of time frame it takes for certain communities to recover,” said Schwing.

Courtesy of College of Marine Science

Although Barnes collaborates with researchers around the world, he mainly works alongside colleagues in the optical oceanography lab at the College of Marine Science.

“An overarching goal of my work is to improve satellite ocean color products and algorithms and make the data more accessible to relevant users,” Barnes said.

He explained that he analyzed satellite data on the expansion of the Port Miami to capture what scientists call the “spatiotemporal frequency of turbidity plumes” resulting from dredging.

Working with others who performed reef surveys, his team was able to further estimate the impact of dredging on reefs.

As a result of this work, the United States Environmental Protection Agency contracted him to capture baseline spatiotemporal plume frequency for another system that is slated to undergo similar dredging.

“I was able to develop a new method of analyzing satellite data, which improved understanding of environmental impacts, and subsequently led to use of satellite data in historical analysis and real-time monitoring of future dredging events,” he said.

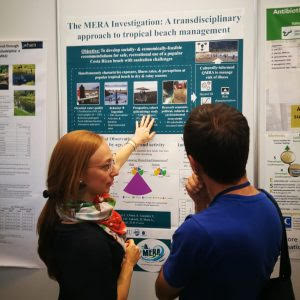

investigation at a conference in Vienna, Austria.

Courtesy of Mera.marine.usf.edu

Symonds works along the beach in Costa Rica in the so-called MERA Investigation, which is named for its acronym in Spanish and stands for “environment, ethnography, risk assessment and water quality.”

Scientists from USF, Southern Methodist University and Costa Rican institutions are collaborating on a water quality investigation that focuses on human behavior, water quality and human health to improve beach management and protect public health.

With water quality measurements and information on environmental change, people’s activities on the beach, and local choices about water management, her team aims to better identify what could potentially damage coastal water resources.

“I hope the study provides data and info that informs future policy decisions related to recreational waters,” she said.