Pictured above: MK Brittain | The Crow’s Nest

By Nancy McCann

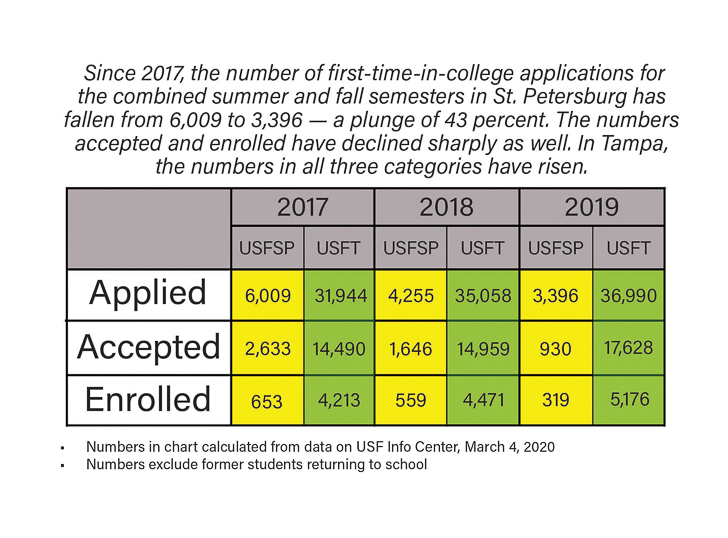

The number of high school students applying to USF St. Petersburg has declined dramatically since the campus began raising its admission requirements to comply with the conditions of consolidation.

Between 2017 and 2018, the number of first-time-in-college applications for the summer and fall semesters combined tumbled from 6,009 to 4,255 – a drop of 29 percent.

Then between 2018 and 2019, the number fell again to 3,396, marking a two-year plunge of 43 percent.

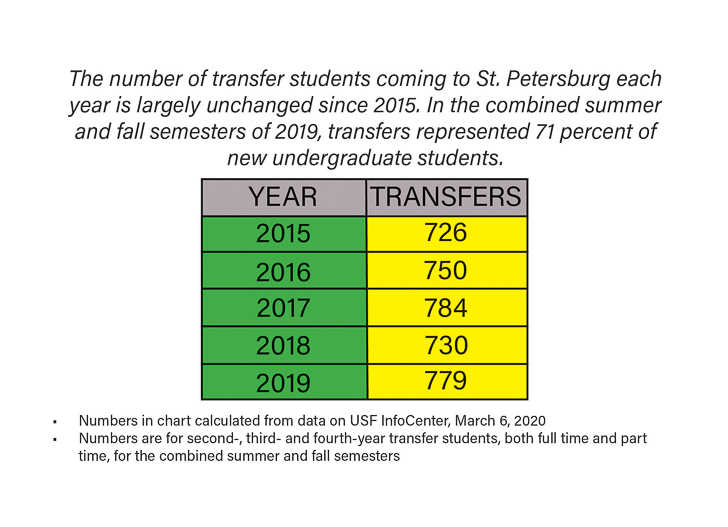

Yet the number of transfer students has essentially held steady.

Transfers hold steady

In 2015, 726 students transferred to the St. Petersburg campus for their second, third or fourth years in the summer and fall semesters. In 2019, there were 779 transfers.

The sharp decline in first-time-in-college applications tracks a similar plunge in enrollment – which The Crow’s Nest detailed in December – and in the number of applicants who were accepted.

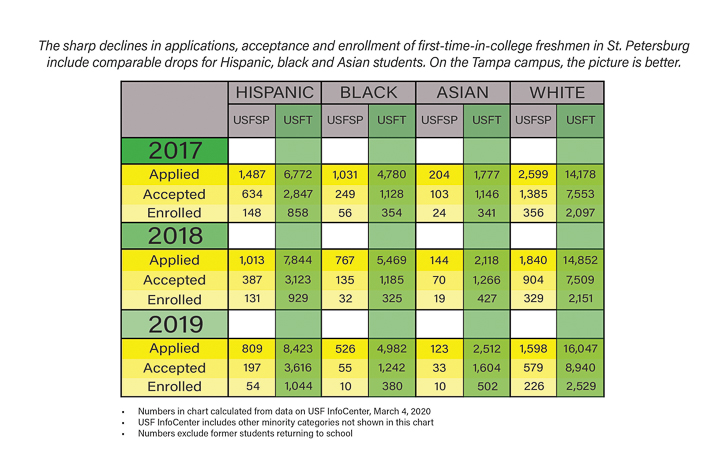

It also reflects sharp declines in the number of minority students in applications, acceptance and enrollment as first-time-in-college freshmen. The white student numbers are down as well.

The diversity picture

USF administrators say the admissions process is complicated, with numerous factors in play.

The downward admissions and enrollment trends are a temporary and expected consequence of consolidation, they say, and should rebound in a couple of years.

The university’s tougher admission requirements are not going unnoticed in Pinellas County’s high schools, which for decades have sent a huge number of students to USF St. Petersburg.

“Only the top 10 percent of students in most high schools are eligible to even apply” now, said Kerrale Prince, who is a coordinator of the Pinellas school system’s AVID program, a national nonprofit that helps under-achieving students tap into their potential.

“Extremely competitive entry requirements are discouraging to most (high school) students,” said Prince, who is based at Countryside High School in Clearwater.

“I have seen an increase in student anxiety, stress related illness, mental illness, apathy toward college and apathy towards education in general,” Prince said in an email to The Crow’s Nest.

At the heart of the plummeting first-time-in-college numbers is an abrupt shift in direction for the campus that the Legislature set in motion two years ago. That’s when it decided to end St. Petersburg’s independent accreditation and roll the three campuses of the USF system into one consolidated university dominated by Tampa.

For decades, USF St. Petersburg’s role in the higher education landscape of west-central Florida was clear.

It was a campus that embraced students who might not be accepted at larger state universities, especially non-traditional students and some minority students, and let them linger if they wanted to experiment and change majors.

But now, with consolidation set to begin July 1, the St. Petersburg and Sarasota-Manatee campuses must improve their metrics in admission requirements, retention and graduation rates, and other academic yardsticks.

Those are the metrics that enabled USF Tampa to become one of three “preeminent research institutions” in the state university system in 2018.

Starting in 2022, the two smaller campuses must join in meeting those metrics.

Keeping the preeminence distinction is the top priority of Tampa-based administrators and the USF system Board of Trustees.

The Pinellas County legislators who engineered the USF consolidation repeatedly offered one overriding reason for the move:

As a preeminent state university, USF Tampa gets extra state funding each year. By consolidating, some of that money also would flow to St. Petersburg and Sarasota-Manatee.

But the Legislature also decided that the two smaller campuses did not have to meet the metrics for preeminence until 2022 and therefore were not eligible for a share of preeminence funds until then.

That means St. Petersburg is being forced to rapidly raise its metrics and so-called “student profile” – and is seeing a corresponding drop in first-time-in-college applications, admissions and enrollment – without getting any of the preeminence money.

A school’s student profile is the average GPA and standardized test score of the students it admits – one of the first things students applying to college want to know.

The marching orders from the Legislature and Tampa-based administrators have left some leaders of the St. Petersburg campus fuming.

One of them is history professor Ray Arsenault, who as president of the USF St. Petersburg Faculty Senate has repeatedly criticized the roll-out of consolidation and confusing, sometimes contradictory policies coming from Tampa.

“All (Tampa administrators) can see is metrics,” Arsenault said last year. “Their bottom line is (maintaining USF’s) preeminence.”

What he calls the “get-‘em-in, get-‘em-out” fixation on student retention and graduation rates is a “formulaic march to graduation (that) is intellectually destructive,” Arsenault said.

St. Petersburg began raising its admission standards even before the Legislature sprang its surprise move on consolidation, which was enacted into law in March 2018.

Two months earlier, the campus had stopped accepting high school graduates with a GPA lower than 3.0.

University administrators said they hiked the admissions threshold to improve incoming students’ chance of academic success, and this decision was made before they were aware that the Legislature was considering consolidation.

In 2017, the campus’ student profile for the fall semester was a 3.82 high school GPA and a 1208 SAT or 26 ACT score. In 2019, the profile rose to a 4.12 GPA and a 1255 SAT or 28 ACT.

Patricia Helton, the St. Petersburg campus’ regional vice chancellor of student affairs and student success, said in an interview that caution must be used in focusing on student profiles because they are averages, not what a student must have to be accepted to the university.

“My fear is that the student profiles get out there and that’s what (prospective students) think they must have to apply,” she said.

In addition to the higher admissions standards, Helton said, it is “almost impossible” to identify everything else that is contributing to the lower number of applications in St. Petersburg.

“Admissions are complicated, and consolidating the admissions process can’t be done overnight,” she said.

Other administrators have noted that the number of college students is down around the country and in Florida, and that there is less interest in a college education when the economy is strong and good jobs are plentiful.

According to a Dec. 16, 2019, article in Forbes magazine, there was a 1.3 percent decrease in nationwide college enrollment from fall 2018 to fall 2019. In the same time period, Florida’s enrollment decreased by 5.3 percent.

The largest national decrease was at private four-year institutions (down 2.1 percent). Public four-year institutions were down by 1.2 percent.

Paul Dosal, the USF system’s vice president for student success, said in an interview that it is important to include transfer students when scrutinizing admissions and enrollment in the USF system.

“The focus has too often been here and elsewhere on FTIC (first-time-in-college) enrollment,” said Dosal. “I just have to stress that more than 50 percent of our students enter as transfer students.”

The total number of transfer students at the St. Petersburg campus in the 2019 fall and summer semesters (779) was up by 7.3 percent from 2015 (726).

Even so, 2020 targets for first-time-in-college enrollment in St. Petersburg are still low compared to the years before 2019, according to numbers provided to The Crow’s Nest by Glen Besterfield, USF dean of admissions and associate vice president of student success and student affairs.

The number targeted for freshman enrollment in the 2020 summer semester is 171 and the target for fall is 161.

In 2017, first-time freshman enrollment was 253 in the summer semester and 400 in the fall.

Dosal said it’s also important to look at the big picture of student success.

“We don’t serve students well by admitting them only until you lose them the next year or they fail to earn a degree after trying for two years and racking up some debt,” he said.

That’s why Regional Chancellor Martin Tadlock likes to talk about retention rates — the percentage of a school’s first-year undergraduates who continue at that school the next year.

It is “remarkable” that the projected freshman retention rate for students who entered USF St. Petersburg in 2018 is over 82 percent, he said. The national average retention rate is 75 percent.

What is the amount of preeminence funding that USF has received each year (including projected for 2020/21) since being awarded preeminence status?

New Crow’s Nest story on preeminence fundinghttps://crowsneststpete.com/2020/04/12/wheres-the-money-once-again-no-new-funds-in-preeminence-pot/

USF Tampa received $6.15 million in preeminence funding in 2018-19. The Florida Legislature did not provide preeminence funding in 2019-20. The Crow’s Nest is determining what the outcome will be for 2020-21. Once preeminent funds are received in any year, the amount is recurring even if new awards are not made.