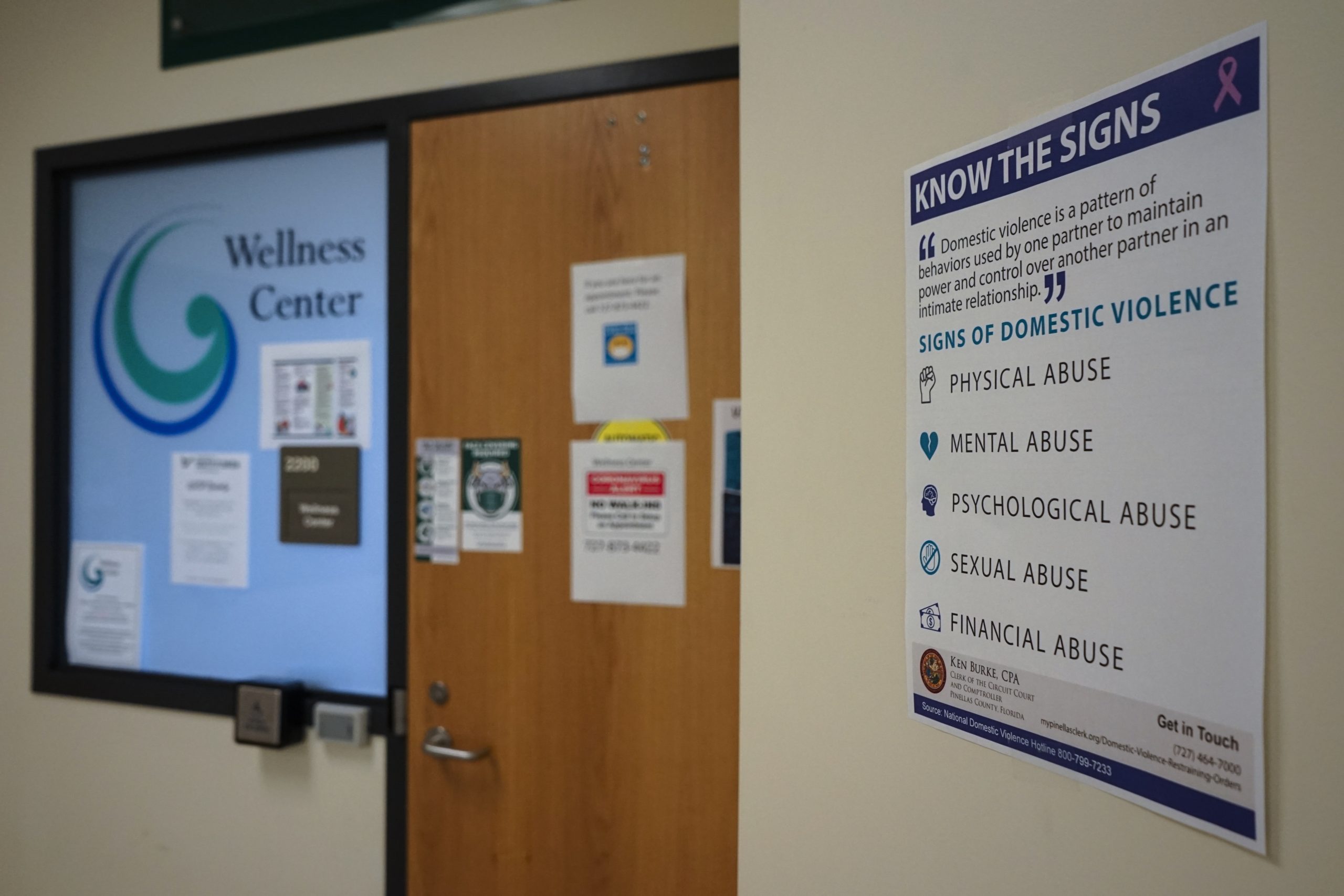

Pictured Above: Posters relating to mental health hang outside the Wellness Center. The Wellness Center is one of three departments that handle mental health concerns in students.

Patrick Tobin | The Crow’s Nest

By Catherine Hicks

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among college students and it’s estimated that roughly 40% of students in college experience a significant mental health issue.

Despite its prevalence, schools struggle to overcome the barrier the mental health stigma creates between students and the services available to them.

To many students at USF St. Petersburg, the stigma of mental illness and the mental health system in place can make it difficult to share their struggles with professors, faculty – or even peers.

“Sometimes, I just feel like I’m drowning under the pressure of homework, class work and regular work and I am so overwhelmed and exhausted (that) the idea of going to class and having to interact is just too draining for me, so I will pretend I have or cold or something, because that’s a lot easier to explain and comes with less stigma attached,” said Cynthia Koch, a senior mass communications major.

Other students expressed similar feelings of judgement.

“Sometimes, it would be hard to get out of bed in the morning and skipping that 8:30 Organic Chemistry lecture was a very attractive option,” said Gregory Cote, a first year graduate student in biology. “The next time I would show up in class, students would ask questions about why I missed. If I told them the truth, that I didn’t have the mental strength to leave bed that morning, they would judge me considerably.”

Individuals’ likelihood of seeking treatment for mental health concerns decreases significantly when there are high levels of stigmatization, studies have shown.

“(There are times) where I’m too anxious to engage in an academic environment, or I cannot find the will to take care of myself, get up, go to class, because everything makes me want to cry, or I’m too numb to care,” said a senior anthropology major, who wished to remain anonymous. “USF St. Petersburg is pretty good about things (regarding mental health) during finals and midterm weeks, but could we possibly have some of (the same awareness) and same resources throughout the semester?”

“Exam weeks are not the only times we’re vulnerable to burnout and mental health crisis.”

During exam and finals week, many universities, including USF St. Petersburg raise awareness of mental health and the resources available to students by sending out email blasters, hosting an event or putting up posters on campus.

Following finals season, the attention surrounding mental health treatment quickly dies down.

A recent study showed that on campuses where students perceived there to be a stigma surrounding mental illness, among both students and administration, students were less likely to seek out treatment, even if it’s available to them.

“There is absolutely a stigma surrounding mental health and while it has improved, I know there are many people, both on our campus and in society, who are reluctant to seek out services because of that stigma,” said Robert McDowell, the coordinator of Student Accessibility Accommodations and Services at USF St. Petersburg.

“It’s one thing to know about the resources available, it’s another to connect with the services.” McDowell said. “Those of us working in these departments are very aware (of) this stigma and work with students to overcome it.”

USF St. Petersburg has three departments that handle mental health concerns in students: The Wellness Center, The Students of Concern Assistance Team (SOCAT) and Student Accessibility Services (SAS).

The Wellness Center provides students with various health services, including but not limited to medical, psychological and preventative services. Students are able to seek counseling as well as psychiatric services at the Wellness Center.

SAS, previously Students with Disabilities Services, “works with students, staff and faculty to promote equitable and accessible education, meaningful self-advocacy, awareness of disability issues and inclusiveness for the USF community,” according to its website.

Currently, SAS provides accommodations to over 100 students for major anxiety or other mental health concerns, but there are many students who don’t take advantage of these services.

Accomodations can include extended testing times, absence forgiveness, the ability to leave during class or any other service the student and their medical professional believe would assist them in their academic success.

“We changed our name from disability to accessibility services so there wouldn’t be so much stigma attached to the name,” McDowell said. “These aren’t disabilities, these are things everyone experiences and everyone needs to be able to access the services when they need them.”

“It really is a kind of awareness effort. It’s our job and our goal to promote knowledge of these resources to the students.”

The Student Toolkit provides students with current resources and information about the departments available to assist them.

SOCAT is “an interdisciplinary team which reviews referrals for students whose behavior presents a disruption to campus or a concern for safety,” according to its website.

When a fellow student or a faculty member is concerned about a student’s safety, from either themself or others, they can anonymously report the student to SOCAT, which then appoints a team member to communicate directly with the student.

“‘Don’t say those things, or I’ll have to report you to SOCAT,’ was a line I heard many times by staff or peer coaches at USFSP,” Cote said.

Once a report has been made, the assigned SOCAT member is responsible for connecting the student with representatives of various departments across the campus that can assist them. Students with mental health concerns are generally referred to the Wellness Center.

To some students, the SOCAT reporting process is invasive and does little to assist students struggling with mental health concerns, but rather further contributes to the stigma among students and staff.

“When I was SOCAT reported, it felt very intrusive,” Cote said. “I felt like the people around me, instead of offering support, pawned me off to a rather unhelpful speech from adults that had no business in my mental health problems.”

“I felt like the staff were more concerned about my GPA and attendance being affected than they were my actual (wellbeing) – when I told them I had A’s in all of my classes, I didn’t receive any other follow-up.”

Most students agree that while progress has been made in destigmatizing mental health, universities have a long way to go in their services and procedures.

“Students should be allowed to have mental health days and some professors should be more lenient and understanding with their attendance policies,” Koch said. “Students, professors and staff should look out for each other; if someone seems off, upset, or is absent constantly, you should check up on them.”

“It doesn’t have to be invasive, a simple ‘hey, how’ve you been? Are you okay? I’m here if you need to talk,’ can really go a long way for those struggling with mental illness.”

Other students mirrored this sentiment.

“The problem (at USF St. Petersburg) is that the resources stop the minute the student decides they would rather stay in bed than go get help… Students should be trained to support their peers and not just report them to SOCAT,” Cote said.

If you are willing to participate in a conversation directing a stigma (sic) at mental illnesses and seeking services for them you are part of that prejudice. Prejudice is the apt and accurate word.

If, on the other hand, you stand up to people taught or teaching it, you stand on the side of change.