Pictured Above: Professor emeritus Darryl Paulson (left) says Tampa’s moves are reminiscent of the “tyranny and intolerance” of yesteryear, while state Sen. Jeff Brandes suggests they may violate “the letter and spirit of the law.”

Courtesy Darryl Paulson and Wikepedia Commons

By Nancy McCann

When Pinellas County legislators moved without warning to abolish the independent accreditation of USF St. Petersburg in 2018, the campus and its allies reacted with loud, hot indignation.

St. Petersburg had grown and thrived since winning accreditation in 2006, they said.

Returning the small, waterfront campus to the control of Tampa, they warned, would jeopardize that growth, especially minority enrollment; weaken the campus’ leadership; and smudge the luster of its unique identity in the higher education landscape of Tampa Bay.

Rep. Chris Sprowls, R-Palm Harbor, the principal architect of consolidation, shrugged off the criticism and steered the bill into law in March 2018.

Consolidation with Tampa, Sprowls said, would be good for St. Petersburg and Sarasota-Manatee, ensuring that the two smaller campuses would get some of the prestige and extra state funds coming to Tampa because of its newly emerging status as a state preeminent research university.

“A rising tide lifts all boats,” Sprowls said repeatedly.

But now, 12 weeks into consolidation, it increasingly looks like the fears of 2018 could have been forecasts. The boats in St. Petersburg are listing badly:

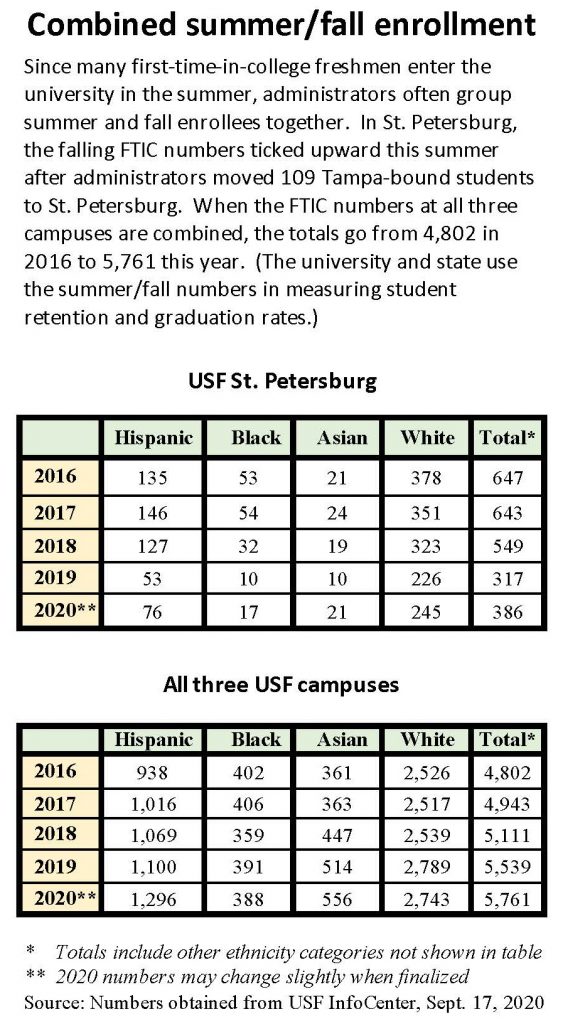

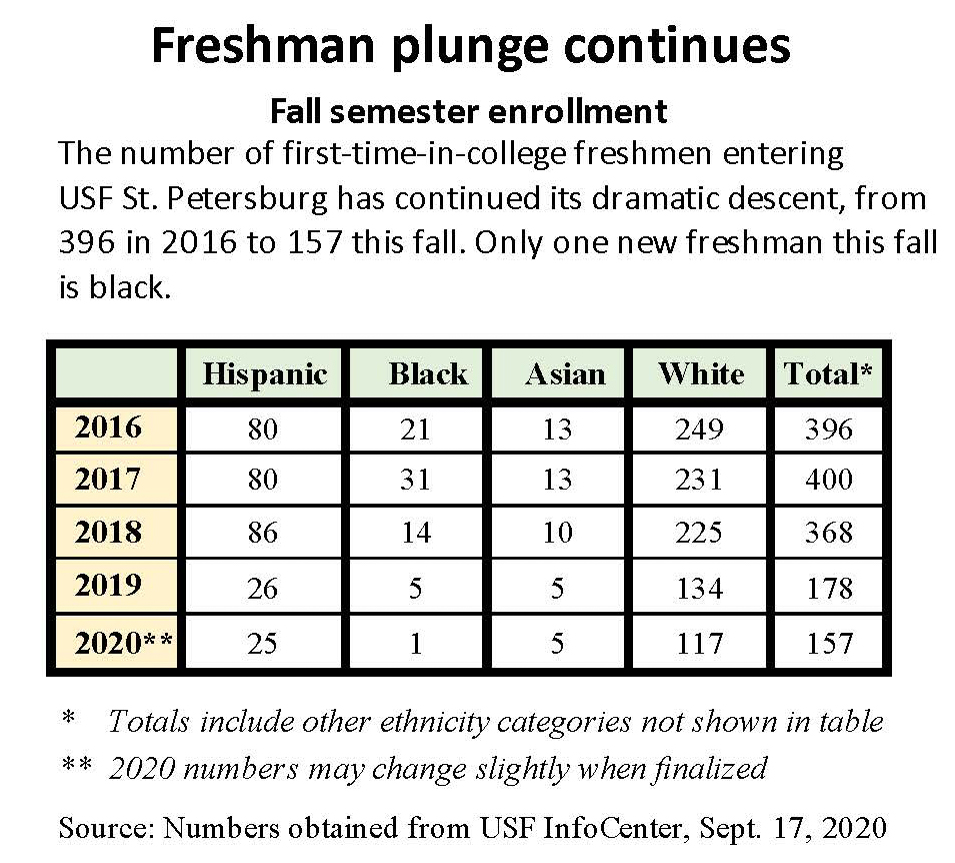

** Since the campus began rapidly raising its admission requirements in 2018 to comply with the expectations of consolidation, first-time-in-college freshman enrollment has plummeted. This fall only one new freshman is black.

** The regional chancellor of St. Petersburg, Martin Tadlock, was supposed to retain authority over a number of campus officials. But key personnel who reported to him now directly report to Tampa, and administrative organizational charts that are making the rounds may suggest other changes as well.

** Tadlock was also supposed to have considerable authority over the campus budget. But there are indications that Tampa administrators are mulling over a plan to consolidate the budgets of the three campuses into one.

** Even the name USF St. Petersburg is kaput. On Aug. 31, the campus was informed that its name is now “USF St. Petersburg campus” – with a lowercase “c.”

Darryl Paulson, a professor of government in St. Petersburg for 35 years, retired in 2009. But he said he remembers well “the bad old days, when there was almost totalitarian control” by Tampa.

“It was a major change and improvement to this campus when we got the separate accreditation” in 2006, Paulson said. “It’s hard for me to understand why Rep. Sprowls and Sen. (Jeff) Brandes would lead the charge to take away the positive things.

“It is almost like the former Soviet Union telling Poland, East Germany, Hungary and the other satellite states that they are better off under the control of the most powerful entity.”

Sprowls has not responded to several requests for comment from The Crow’s Nest in the last three weeks. But Brandes, R-St. Petersburg, said he and Sprowls are monitoring developments in consolidation and will be seeking explanations from the Tampa administration.

“What USF needs to be clear on is that they follow the letter and spirit of the law,” Brandes said. “And the spirit of the law was very clear … to maintain an independent view of the different campuses while putting them under the same umbrella.”

Provost Ralph Wilcox, who appears to be a main driving force behind the changes, did not respond to a request for an interview last week.

If Brandes, Sprowls and the Legislature do intervene, it won’t be the first time.

In 2019, they amended the statutes to ensure that St. Petersburg and Sarasota-Manatee would become full branch campuses, as defined by the regional accrediting agency, with authority over their own budgets and hiring. They also specified that the campuses’ names would remain USF St. Petersburg and USF Sarasota-Manatee.

Twice after that, USF’s new president, Steve Currall, released proposed organizational plans that would have shifted most of the decision-making to Tampa.

And twice Currall had to backtrack after key legislators reminded him to stop trying to maneuver around the law.

“What we (legislators) need is a conversation with the president, and then with the board (of trustees) members and an understanding of why they have chosen to go in certain directions,” Brandes told The Crow’s Nest on Friday.

“I think at the end of the day … the budget is the way that universities predominantly respond to legislative action. Once you start having serious conversations about what their budget looks like next year, they begin to … get the message.”

Plunging enrollment

Wilcox gave what he called his “customary annual reports on enrollment and student profile” to the USF Board of Trustees on Sept. 8, pointing out that it was “the first for the consolidated university.”

It was glowing.

“Thanks to the hard work of so many and the confidence our students and their parents are placing in the University of South Florida, our total headcount enrollment stands at 50,830 across all three campuses today,” Wilcox said, “down just 97 students or 0.2 percent from the fall of 2019 and pretty remarkably in lockstep with the enrollment plan approved by the Board of Trustees pre-COVID-19.”

He said “the diversity of our summer and fall incoming freshman class has shown year-over-year gains,” with new black freshmen up by 1.3 percent, Hispanic by 17.8 percent and Asian by 8.8 percent.

But there is “still some work to do,” he said, on an overall “year-over-year declining proportion” of black students, down 3.2 percent; white students, down 1.9 percent; and international students, down 7.7 percent.

What Wilcox didn’t mention is that the total number of undergraduate degree-seeking students at the St. Petersburg campus is down by 11.6 percent from fall 2019 and 16.4 percent from 2016.

He didn’t mention that the number of undergraduate degree-seeking black students at the St. Petersburg campus is down by 17.6 percent from fall 2019 and 29.1 percent from 2016. Over the same time periods, the total number of degree-seeking white students is down 10.8 percent and 18 percent.

And he didn’t mention that the number of first-time-in-college freshmen at the St. Petersburg campus has stunningly declined, down by 11.8 percent from fall 2019 and 60.4 percent from 2016.

Now the St. Petersburg campus has less than half of the incoming freshmen it had in the fall five years ago, going from 21 new black freshmen to one, and 249 new white freshmen to 117.

The number of new Hispanic freshmen in St. Petersburg has dropped from 80 to 25 and new Asian freshmen from 13 to five since fall 2016.

“Any neutral observer looking at what happened would be drawn to an immediate conclusion,” Paulson said after looking at the newest data. “The numbers are going in the wrong direction.

“The campus has been decimated in terms of overall and minority enrollment.”

It’s the law

During consolidation planning, a task force created by the Legislature recommended that USF St. Petersburg and USF Sarasota-Manatee become full branch campuses as defined by the regional accrediting agency.

That means the two smaller campuses would have strong leaders with substantial authority over academics and budgets.

Or, as Belle Wheelan, president of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges, told The Crow’s Nest last year, a branch campus is “a full-blown operation with someone in charge.”

Legislators, again steered by Sprowls, made it the law: A 65-page education bill passed in May 2019 mandated that when the three campuses of USF were consolidated, St. Petersburg and Sarasota-Manatee would be full branch campuses.

Consolidation became official on July 1.

The law also says that “the Legislature intends that the University of South Florida St. Petersburg be operated and maintained as a separate organizational and budget entity of the University of South Florida.”

And it specifically says that “the (USF) Board of Trustees shall publish and approve an annual operating budget for each campus.”

Last November, at a joint meeting of two trustees committees, Wilcox seemed to surprise some in the audience when he mentioned what he thinks is a rough spot for consolidation: the university’s budget.

“What’s apparent as we wrestle with challenges to dismantle three institutions and rebuild into one is the need for one budget in one university,” he said. “It’s really challenging to have three or four separate budgets.”

Now, there are rumblings on the campuses that Tampa administrators are actively pushing for one budget for the three campuses.

Sen. Brandes said that’s not going to happen.

“I have no doubt that they would like to have one single budget, but the law clearly states that there should be three budget lines,” he said. “We’re not going to let them consolidate budgets. I’m telling you that USF needs to follow the law, period. And the law is very clear.”

Professor Paulson said the budget issue is crucial.

“Old-timers like me and any others who were there under the period of time when the Tampa regime controlled everything — especially the money pot — experienced tyranny and intolerance and frankly discrimination from the Tampa campus,” he said.

The two consolidation organizational plans first proposed by Currall that centralized almost all budget and academic authority on the Tampa campus were replaced — under pressure from all around — with new details that appeared to align with the law and its requirements for branch campuses.

But after Currall released a third plan that was applauded by the St. Petersburg campus and community, organizational changes began happening, according to information that The Crow’s Nest requested from Tadlock.

Principal positions that now have direct reporting lines to Tampa – not St. Petersburg – include St. Petersburg’s marketing and communications director; its chief diversity, inclusion and equity officer; and its associate director of student services research and analytics.

Brandes was also adamant about the organizational structure of the consolidated university.

“What you are going to find is that the Legislature is going to review the lines of reporting in depth and make some pretty strong points that individual autonomy is still to be something that we value,” he said.

Campus identity

At a trustees committee meeting on Aug. 25, Wilcox was emphatic.

Every student, professor and staff member at USF should include the word “campus” with a lowercase “c” in their email signature blocks and “everywhere else that we represent the university,” he said.

It should be “USF Tampa campus, USF St. Petersburg campus, USF Sarasota-Manatee campus,” he said, because the three campuses cannot be “viewed as separate institutions” under single accreditation.

As a result, USF St. Petersburg is doing an inventory to see what signs need to be updated to include the word “campus.”

There will apparently be no such inventory in Tampa, however.

“There’s no need to redo the signs at the Tampa campus because they already have the correct name and logo: University of South Florida,” Carrie O’Brion, St. Petersburg’s marketing and communications director, said in an email. “We could use the same name and logo on our campus if we choose. We have just opted to include our geographic location on some of our signage, which means it needs to be updated to include ‘campus.’ ”

That means prominent signs in St. Petersburg could soon say “USF St. Petersburg campus” while signs on the Tampa campus say “University of South Florida.”

Not so fast, said Brandes.

“The only way I would be comfortable with their proposal is if we shift Tampa to ‘the Tampa campus,’ St. Pete to ‘the St. Pete campus,’ and (Sarasota-)Manatee to ‘the (Sarasota-) Manatee campus,’ he said.

“It’s hard to argue that we can’t have individual campus names, but all the campuses need to be treated the same.”

Brandes said there doesn’t need to be “all kinds of internal consternation” about signs.

“What we passed as a law is that USF St. Petersburg gets to keep its own name,” he said. “Let’s focus on the things that really matter.

“And the things that really matter are not that we spend tens of thousands of dollars modifying signs; it’s that the students are getting the academic outcomes that we ultimately want.”

USF spokesperson Adam Freeman has said the administration is “very cognizant” that state law and “local public sentiment” favor preserving the names USF St. Petersburg and USF Sarasota-Manatee.

A shortage of advocates

In the weeks since consolidation took effect, the St. Petersburg campus has lost some of its advocates.

The USF St. Petersburg Faculty Senate, which often looked askance at Tampa administrators, was disbanded, and its outspoken president, history professor Ray Arsenault, is retiring in December.

Much of St. Petersburg’s decades-old Student Government has been subsumed by a new, three-campus system dominated by Tampa students.

For months, editorials in the Tampa Bay Times scrutinized the consolidation process, first criticizing legislators for rushing their plan, then calling on lawmakers and consolidation planners to “maintain and enhance …. (the) unique identities” of the smaller campuses.

The paper warned Tampa administrators against trying to “micromanage (St. Petersburg) from the main campus in Tampa” and chided then-President Judy Genshaft for her “initial lack of candor” when legislators sprang their plan to abolish St. Petersburg’s independent accreditation.

Tim Nickens, the longtime editor of editorials, retired in May. Since then the Times editorial board has been silent.