Pictured Above: USF administrators need to be “trained in diversity and inclusion,” says Spanish professor Pablo Brescia (left). Around the country, faculty of color have a “sense that universities aren’t doing enough” to be inclusive, acknowledges Elizabeth Hordge-Freeman, USF’s interim vice president for institutional equity.

Courtesy of USF

By Nancy McCann and Janel S. Cooper

During his 17 years at USF, Spanish professor Pablo Brescia has watched as the number of Hispanic faculty at the university has slowly inched higher.

But while 22 percent of the undergraduates now attending USF’s three campuses are Hispanic, the percentage of Hispanic faculty members has reached only 6 percent.

“I’m Hispanic faculty, and I feel invisible,” Brescia said. And there’s more to it than the low numbers.

“There’s the story behind the numbers,” he said. “I think the word that encapsulates the state of Hispanic faculty is neglect.

“We have very few faculty overall; we have very, very few faculty … where they can make decisions in administrative positions.”

Across the university, just seven of the 134 people in faculty leadership positions – deans, department chairs or directors – are Hispanic, according to fall 2020 data from USF’s Office of Decision Support.

“They (many faculty and administrators) think along the lines of hiring people of color as that’s going to be enough for diversity,” Brescia said. “I strongly believe that is not the case.”

Although hiring practices are “very important,” administrators need to be “trained in diversity and inclusion …. to be trained to understand there is something called ‘implicit bias,’ to understand there is something called ’racialized answers,’ ” Brescia said.

The disappointing Hispanic statistics and Brescia’s pointed criticism mark another chapter in a year of reckoning for USF on diversity, inclusion and racism.

While America reeled from high-profile black deaths at the hands of police, a resurgence in the Black Lives Matter movement and – in recent weeks – a string of hate crimes against Asian-Americans, USF has faced its own challenges:

** In June, 88 black faculty and staff sent a call to action to President Steve Currall urging the administration to train university leaders in sensitivity and multicultural competence, evaluate pay disparities and expand Africana and Latin American studies.

** In September, all six members of the Diversity Committee at the College of Arts and Sciences resigned in a stinging rebuke of the Currall administration, which it accused of ignoring them. Brescia was the chair of that committee.

** In November, in a report titled “Time stands still in hiring of black faculty,” The Crow’s Nest disclosed that in 2019 only 4.9 percent of the faculty members in St. Petersburg and 5 percent of the faculty in Tampa were black – a statistical picture that was essentially unchanged over the last decade.

The article followed several Crow’s Nest reports since 2019 that new black freshman enrollment on the St. Petersburg campus has plunged in recent years. Last fall the university reported only one new black freshman at the campus.

As the controversy and criticism grew, Currall and his administration responded with a series of moves.

The president pledged to increase diversity and inclusivity, redouble efforts in the hiring and promotion of minority faculty, aggressively recruit minority students and reach out to the black community.

He created a task force to oversee $500,000 in research projects on racism, launched training sessions on diversity and deplored the attacks on Asian-Americans.

In December, Currall also announced a new anti-racism website, which he called “a collective resource and information warehouse for content related to USF’s commitment to anti-racism.”

Diversity, anti-racism and equity performance dashboards are a main feature of the website. It says faculty data is “coming soon.”

Elizabeth Hordge-Freeman, who on April 2 became USF’s interim vice president for institutional equity, said the faculty dashboard will be up in about a month.

Hordge-Freeman was the sociology professor who organized the letter signed by 88 black faculty and staff last June. Two months later, Currall made her his senior adviser on diversity and inclusion.

She told The Crow’s Nest that she “can’t speak directly” to Brescia’s experiences, “but what we do know is that across the country we see a similar response of faculty of color that there’s a sense that universities aren’t doing enough to cultivate a more anti-racist and a more inclusive campus environment.

“The metrics aren’t just the numbers, it’s about being able to . . . stop a faculty member of color on campus, a Latinx faculty member,” she said. “I want to be able to ask them how they’re doing, and for them to respond and say, ‘I feel supported here, I feel part of the community, I feel like I belong here.’ If Dr. Brescia feels invisible, then there’s more work for us to be doing.”

In interviews with the newspaper, Hordge-Freeman and other administrators stressed that USF must do a better job of recruiting faculty of color in what Regional Chancellor Martin Tadlock called “a very competitive marketplace.”

It’s not enough to post faculty jobs when they come open, the administrators said.

The university must identify and cultivate potential candidates of color much earlier – see “who’s out there, who’s in the pipeline, who’s going to be graduating, and reaching out to them and starting to develop a relationship,” said M. Dwayne Smith, USF’s senior vice provost and dean of the Office of Graduate Studies.

The numbers

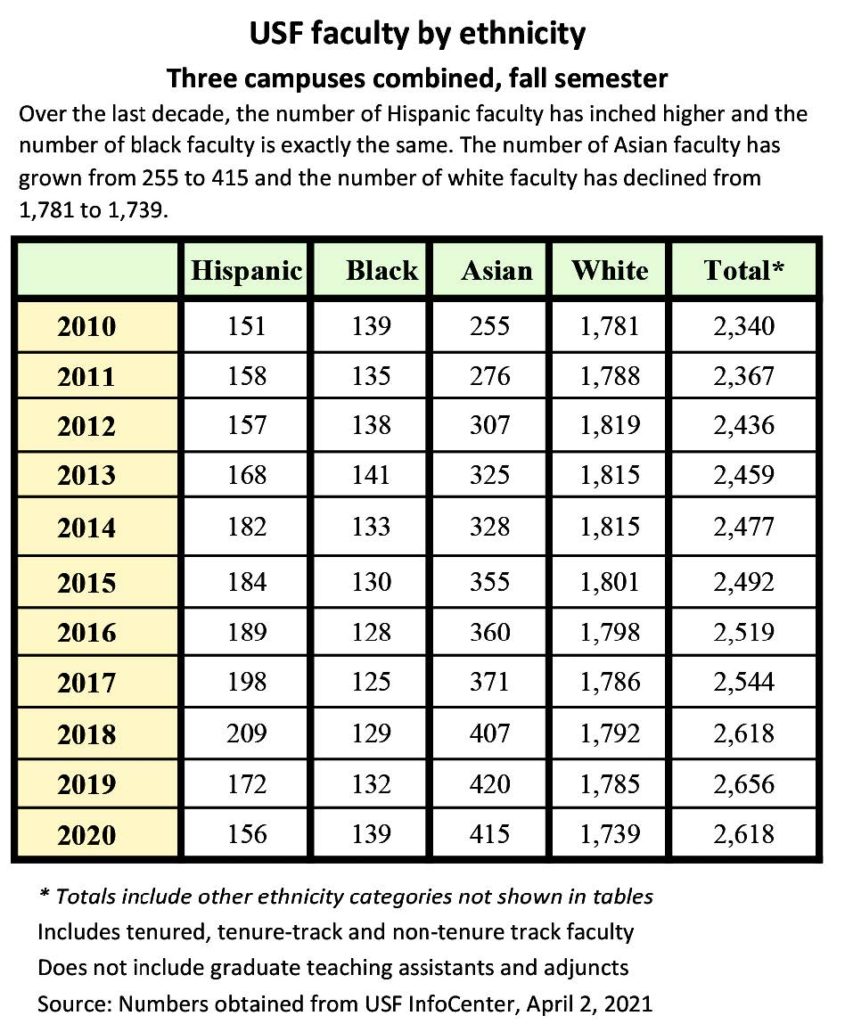

While the number of Hispanic faculty at the USF Tampa campus over the past 10 years during the fall semester has slightly increased – from 133 in 2010 to 145 in 2020 – St. Petersburg’s count over the same time span has dropped from 12 to 10.

In St. Petersburg, 17 percent of the undergraduates and 6 percent of the faculty are Hispanic, based on fall 2020 numbers from the USF InfoCenter.

For the three USF campuses combined the number of Hispanic faculty is almost unchanged over that decade, going from 151 in 2010 to 156 in 2020. But there were years when Hispanic faculty totals were much higher, reaching 209 in 2018.

Tadlock said the university’s Hispanic student-to-faculty ratio is “unacceptable,” but some “specific things” are being done to improve faculty diversity.

He said the hiring policy was revised about two years ago, with changes including approval of “every pool of candidates” by university diversity personnel, even if it requires extending the search with additional recruitment to ensure a “diverse pool of candidates.”

The members of each search committee meet with human resources staffers on “best practice procedures regarding fair and unbiased searches,” he said, and positions are advertised in “publications that reach diverse groups of people” using “language (that) is sensitive to cultural differences.”

Another view

At least two Hispanic faculty members at the St. Petersburg campus don’t share Brescia’s sentiments about feeling invisible.

They are two of the campus’ four political science professors.

Luis Felipe Mantilla is an associate professor and associate chair of USF’s Political Science Department.

“My department is very welcoming … being Latino doesn’t particularly affect how they deal with me,” Mantilla said.

But Mantilla said he would “embrace efforts to increase diversity, particularly in leadership positions where it is so lacking.”

Arturo Jimenez-Bacardi, an assistant professor of political science, said he “felt like our small department was very inclusive towards Latinos.”

He said he thinks the trend line on inclusivity is “improving in the right direction.”

“I’m encouraged that I see more Latinos and African Americans publishing in political science journals. There’s more of them in conferences, there’s more of them writing books, there’s more of them in faculty across the United States.”

Only 5 percent of college and university faculty in the United States are Hispanic compared to 20 percent of undergraduates, according to a 2019 Pew Research Center study on recent education statistics.

“The higher you go up in education, the smaller the number of people of color that you see and interact with,” Jimenez-Bacardi said. “I normally had that experience moving along – all my mentors were white people – until I got to USF St. Petersburg.”

One of the main issues with the lack of diversity among faculty is that students may not see themselves reflected in their professors, which can impact student retention as well as enrollment rates, according to a 2019 Forbes article on faculty diversity.

“I’ve had many students, particularly students of Latinx background, respond very positively to my Latinx background,” Mantilla said.

Brescia remains disenchanted.

“The black faculty went to the press (in June) and then had a meeting with the president; they earned a meeting . . . and now they have a group and now there are some things going on,” he said.

“This should not be like this; administrators should lead in this issue instead of thinking about the (university’s national) rankings. They should be thinking about how diverse and inclusive we want our campus to be.”

The term Hispanic was used in this story as interchangeable with Latino and Latinx because the university uses Hispanic as the ethnicity category in the databases accessed. Elizabeth Hordge-Freeman and M. Dwayne Smith confirmed that the data reported as Hispanic includes students and faculty who may prefer Latino and Latinx.