Courtesy of Matt McCann

By Nancy McCann

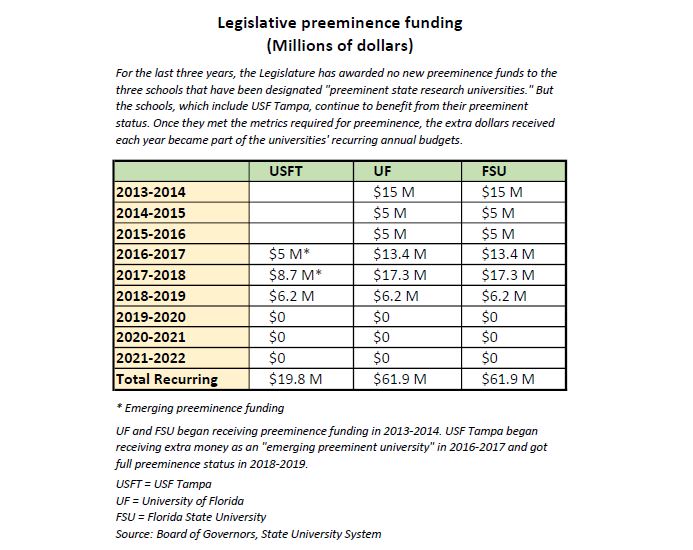

For the third year in a row, the Florida Legislature has awarded no new preeminence funds to USF and the state’s two other preeminent research universities, the University of Florida and Florida State.

Wait.

Didn’t the Legislature create the much-ballyhooed preeminence program back in 2013 to encourage Florida’s public universities to improve their performance and enhance the state’s less-than-sterling reputation in higher education?

Didn’t USF Tampa make achieving and maintaining preeminence its No. 1 priority for years, pushing up its academic metrics to bring extra funding from the state and help the university achieve higher national rankings?

And didn’t the Pinellas County legislators who orchestrated the surprise move in 2018 to abolish USF St. Petersburg’s independent accreditation promise that consolidating with Tampa would give St. Petersburg a jolt of prestige and a share of the preeminence dollars that were coming to the Tampa campus?

So where’s the new money? Has preeminence become a passing fad in the state capital?

Darryl Paulson, a professor of government who taught at USF St. Petersburg for 35 years before retiring in 2009, typifies the viewpoint of preeminence skeptics.

“It can be said that USF has fared as well as UF and FSU in preeminent funding the past three years: None of them has received a penny (in new money),” he said.

Citing the statistics for the last six years (see chart, above), Paulson said, “For funding to be effective, it must be consistent. You can’t receive (new) funding for three consecutive years and then nothing for the next three years. It becomes difficult for effective long-range planning.

“Here today, gone tomorrow.”

But a key legislator said that lawmakers have not abandoned new preeminence funding for the long term.

“No, I don’t think so,” Sen. Jeff Brandes, R-St. Petersburg, told The Crow’s Nest. “I think the Legislature is committed to have upper-tier universities in Florida. We know what it takes to get there, and I think the Board of Governors (the state agency that oversees Florida’s 12 public universities) will continue to push us forward.”

The preeminence money awarded in previous years is now part of the three universities’ recurring budgets, he and other legislators say, and those funds have helped the schools bolster key programs, research and faculty.

Despite the Legislature’s recent stinginess on preeminence funding, legislators and some university leaders say preeminence is more than just the money.

The label “preeminent state research university” brings a cachet that helps in recruiting students and faculty, they say. It should also help USF reach its goal of membership in the Association of American Universities, an elite group of 64 public and private schools in the United States and two in Canada that are considered leaders in innovation, scholarship and contributions to society.

“’Preeminence’ does carry with it a connotation of excellence or quality that enhances the reputation of the university,” Tampa-based professor Tim Boaz said in 2019. Boaz is now president of the USF Faculty Senate and a member of the university’s Board of Trustees.

As Boaz and legislative leaders note, even though the Legislature has turned off the spigot for new preeminence money for the third year in a row, USF Tampa, UF and FSU continue to benefit financially from their preeminence status.

Once they met the metrics required for preeminence, the extra dollars received each year become part of the universities’ recurring budgets.

Truth be told, the $19.8 million in recurring preeminence money is a tiny fraction – about 2 percent – of USF Tampa’s annual operating budget of $859 million. (The university’s total operating budget, which includes USF Health and the St. Petersburg and Sarasota-Manatee campuses, is $1.8 billion.)

And despite the lofty promises of the Florida legislators who engineered the consolidation of USF’s three campuses, which took effect last July, St. Petersburg and Sarasota-Manatee aren’t even eligible to get a slice of Tampa’s preeminence funds until the fiscal year that begins in July 2022.

Under state law, “only the performance of the USF Tampa campus is used to determine eligibility for preeminence through the 2021-22 academic year,” university spokesperson Adam Freeman said in an email to The Crow’s Nest.

It is still unknown how much the St. Petersburg campus will benefit.

“Once preeminence eligibility factors in the performance of all USF campuses starting in the 2022-23 academic year, university leadership will evaluate how to invest any funds earned through preeminence across the university,” Freeman said.

A ‘lackluster’ commitment

Charlie Reed, who led the Florida university system between 1985 and 1998, once famously lamented that the state’s unofficial slogan was, “We’re cheap and we’re proud of it.”

In fact, for years Florida was known for what the St. Petersburg Times (now the Tampa Bay Times) in 2012 called a “historically lackluster financial commitment to higher education.”

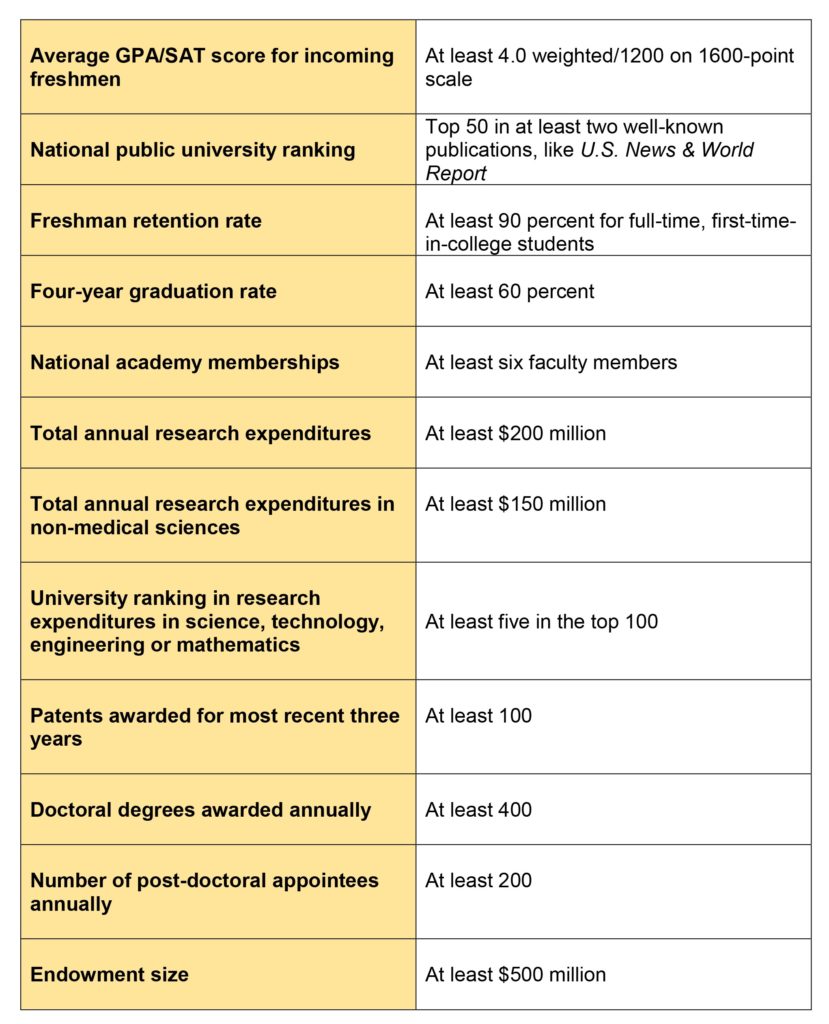

Amid such criticism, the preeminent university program was created by the state in 2013 to reward high achieving universities that meet or exceed 11 of 12 benchmarks – or metrics – of excellence.

They include certain levels of achievement for new freshmen entering in the fall, student retention and graduation rates, research expenditures, size of endowment and the number of patents awarded to research faculty (see chart, below).

The University of Florida and Florida State were awarded preeminent status – and $15 million each in extra funding – in 2013-2014, a designation they have maintained ever since. New preeminence funding dollars varied each year through 2018-2019.

USF Tampa was designated an “emerging preeminent” university in 2016-2017 (which meant $5 million in extra funds) and 2017-2018 ($8.7 million) and achieved full preeminence in 2018-2019 ($6.2 million). (See chart, above).

But since 2018-2019, legislators have added no new money to the pot.

Even without new preeminence funding, USF Tampa, FSU and UF still benefit from their state status. Once they met the metrics required for preeminence, the extra dollars received each year became part of the three universities’ recurring budgets.

But USF Tampa, the university most recently designated as preeminent, has a significantly smaller amount in its annual budget from preeminence funding than FSU and UF, which started receiving it earlier.

USF Tampa has $19.8 million in its recurring budget due to prior years’ preeminence funding (including the emerging preeminence years) while FSU and UF each have $61.9 million.

The positives of consolidation

Brandes and state Rep. Chris Sprowls, R-Palm Harbor, helped orchestrate the consolidation of USF’s three campuses, a move they said would eventually bring some of Tampa’s preeminence money to the two smaller campuses.

Sprowls, who is now House speaker, did not respond to questions from The Crow’s Nest. But in an email to the newspaper last year, he brushed off a question about the lack of new preeminence money and stressed what he called the positives of consolidation for St. Petersburg.

Consolidation means the campus will be part of a “Tier 1” research university and its students will “have access to more and better programs,” Sprowls said then.

In addition, the St. Petersburg campus received an extra $6.5 million in “operational support” in 2019-2020 and 2020-2021 to help it prepare to become part of a consolidated, research-intensive university, he said.

The Crow’s Nest sought comments last week on the status of preeminence funding from the four legislators who chair the education committees and the appropriations subcommittees on education in the Senate and House: Sens. Doug Broxson, R-Pensacola, and Joe Gruters, R-Sarasota, and Reps. Rene Plasencia, R-Orlando, and Amber Mariano, R-Hudson.

None of the four responded.

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic last year, USF’s financial picture spiraled downward as revenue sources like state sales taxes, lottery sales, athletics, and dormitory and dining fees declined sharply.

As the USF administrative began to cut spending this year and prepared to cut $36.7 million in the fiscal year that begins in July, some faculty leaders reacted with loud dismay.

They have repeatedly denounced the administration for what they call a secretive, hasty approach to planning and budgeting, and some faculty have sharply criticized the leadership’s emphasis on national rankings and the academic metrics that figure in preeminence.

“Though our decades-long ascent up the ladder of national recognition is a real achievement, it has been a costly one,” leaders of USF’s College of Arts and Sciences said in an Oct. 30 memo.

“USF has chased regional and national rankings for years, in the expectation that recognition and rewards would be proportional to our progress as measured by such yardsticks,” the Arts and Sciences leaders said.

“That we have been disappointed in this expectation does not mean the strategy should be abandoned altogether, but it does suggest that the urgency with which we pursue it should be tempered by experience. We cannot continue to do what we have done before, repeatedly, and imagine that this time the outcome will change.”

At least for now, USF’s once-bleak financial picture has brightened considerably. The proposed state budget approved by the Legislature on April 30 and sent to Gov. Ron DeSantis is not as gloomy as officials long feared.

A recent improvement in state sales tax revenue and a huge infusion in federal stimulus money covered most of the anticipated losses in 2021-2022.

What are the 12 metrics of preeminence?

Preeminence was created by the Florida Legislature in 2013 to give extra funds to the state universities that meet at least 11 of 12 metrics – or yardsticks – that legislators established and re-examine each year.