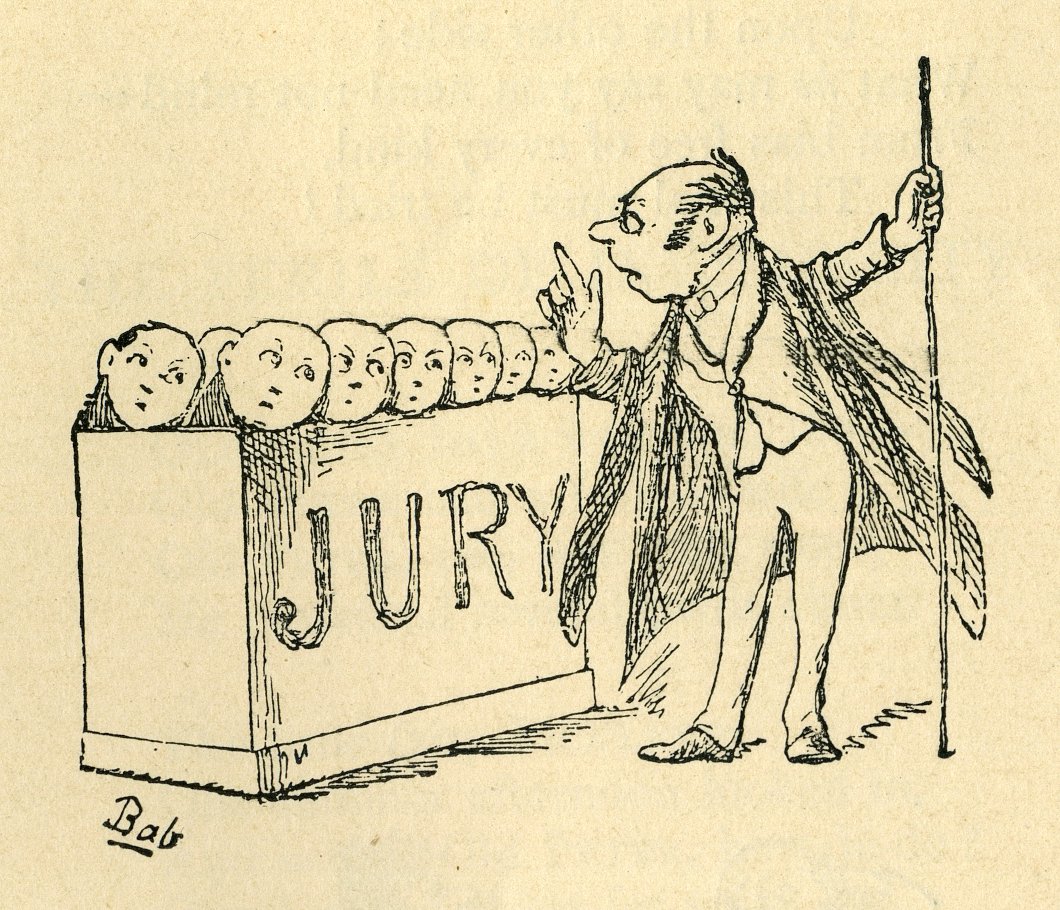

An illustration from 1890 depicting jury trials by Gilbert Sullivan.

Courtesy of The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive

By Preston Kifer

When you think of a court trial, what comes to mind? Perhaps you think of the dramatic monologues given on “Law & Order, or maybe your mind wanders to your favorite courtroom drama.

Whatever it may be, much of public perception about attorneys and how they act in court comes primarily from the media we consume.

That said, our understanding of attorneys as impassioned speakers fighting tooth and nail for justice may not be too far from reality.

In my eyes, a real courtroom trial is basically theatre — the courtroom is the stage, the judge and the jury are the audience and the attorney is the actor.

I have done theatre for most of my life, but now I am more focused on law. However, my theatre background has not been lost in my new passion, but rather embraced.

When acting in a show, the goal is simple: tell a story. An actor uses dialogue, emotion and physicality to express everything to the audience. They connect emotionally with their audience in order to make things more believable and to immerse them in their world.

That’s exactly what an attorney does.

In a trial, an attorney will give opening statements, examinations and closing arguments to an audience, the jury and the judge to convict or acquit the defendant.

In an opening statement, an attorney will lay the groundwork and basis for what kind of story they are telling — very similar to the opening number of a musical.

During examinations, a witness will be questioned by the attorney so the judge and jury can understand what has happened — like lines in a play.

The trial finishes with a closing argument, where the attorney will bring together everything in a bombastic ending — like the finale of a show.

The testimony that is laid before the courtroom and the defendant’s alleged offense are like the driving conflict behind it all.

In a trial, the jury is the one deciding the fate of the accused. Often, they do not care about rules or objections. Rather, they enjoy hearing a story. You want the jury to listen to your story so they’ll rule in your favor, and the better storyteller you are, the more your audience engages.

People often think of attorneys as cold and calculating, but a good attorney needs to be able to connect to people on a deeper level.

Christopher Nickerson, a freshman political science major at the University of South Florida Tampa campus also believes there is a correlation between theatre and law.

“I believe that theatre can relate to law. You can present a case the same way you act out a part. You can prepare for a scene the same way you can prepare for an opening statement. The art of preparation can be found in both law and theatre which is why I believe they are similar,” Nickerson said.

Katherine Metheny, a senior political science major at the Tampa campus, had similar thoughts.

“Just like an actor in a play, a lawyer must tell a convincing, entertaining and moving story to the jury. Though the merit of an argument is not purely based on performance, good presentation certainly helps,” Metheny said.

There are even pre-law organizations on campus that take this approach. USF Mock Trial, a pre-law organization dedicated to competing against other schools in fake trials, talks about the use of theatre concepts when practicing statements or when training witnesses to give testimony in trial.

As a pre-law student, I firmly believe that my background in theatre has boosted my abilities. I recommend other pre-law students to study techniques used in theatre and it should be taught as part of the law curriculum.

Preston Kifer is a sophomore political science and theatre major with a minor in legal studies at the USF Tampa campus.