Photo by Alisha Durosier | The Crow’s Nest

By Alisha Durosier

The restoration of the Williams House, funded by the 2022 $280,640 matching grant from the Florida Division of Historical Resources, has been making progress.

The current phase of restoration started in 2020 when the Florida Division of Historical Resources awarded the campus a $17,837 grant. The university matched the grant, allocating $35,674 to develop a master plan which was later submitted as part of the 2022 grant proposal.

Susan Toler, USF St. Petersburg’s campus associate dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, authored both grants in collaboration with Paul Palmer. He is an architect from Renker Eich Parks Architects, whom the university partnered with to restore the Williams House.

The 2022 grant, which totaled $561,280, was intended to cover all exterior restoration and repairs of the house. However, the total repair costs exceeded the budget by 40%.

“It was very an agonizing process to try and figure out how are we’re going to do this now?” Toler said.

According to the project’s grant administrator, situations like this are common and advised the committee overseeing the project to reallocate restoration projects to stay within the budget.

“So, we did that,” Toler said. “The most important thing was there was damage to the foundation, it had eroded.”

Part of the main porch was sinking, leading to sloping floors and misaligned windows. In response, architects shored and jacked up the house to replace portions of the foundation and any wood that was damaged by termites.

Much of the porch, including the flooring, ceiling and balustrades were replaced. The balustrades in particular had to be hand-crafted to replicate the owl motif that was carved into all of the porch railings.

“One of the things that most people don’t know is that when you do historic preservation, you can’t just have an average licensed carpenter come in and do the work. You have to have real trade craftsmen come and actually replicate some of the original work,” Toler said.

For historic buildings, the National Park Service has a set of guidelines and standards architects are required to uphold in historic preservation.

“The overall, overarching theme is historic preservation. That’s the blanket category. Under that, there’s restoration, rejuvenation, rehabilitation and repairs. Those are all subcategories of historic preservation because preserving history is the main goal,” Palmer said.

Considering the historical significance of the Queen Anne-style house, architects aim to preserve as much original material as possible, replacing and repairing only what is necessary.

“Sometimes you have to actually replace the original material because it is in such bad condition, that would be restoration or if it’s extensive, reconstruction,” Palmer said.

Palmer emphasizes that the “boring” materials such as the wood carries just as much historical significance as any other component of the house.

“That wood was harvested probably by old trees in Florida, really hard wood before they were all cut down,” Palmer said. “They were also fashioned and processed by historic figures, like all of the workers of the time. It has the touch of the people of the time.”

The house’s structural integrity is attributed to the use of heart pine wood. The house — like many historic buildings — is built from this material. Heart pine is derived from mature longleaf pine trees, the remaining of which are now protected by law, making heart pine largely unavailable.

Reconstructed areas of the house were built with kiln-dried, pressure-treated wood, which will help protect the house from termite infestation and rot. The kiln, which is an oven often used to dry, harden or burn materials, was mainly used to replicate the original color of the heart pine wood.

Toler authored two more grants to continue the restoration efforts.

The first and largest grant is for $274,550, to finish all exterior repairs. This includes adding hurricane protection to the house, repairing the roof and a full exterior painting. The second grant is for $2,745 to develop a plan for the interior restoration of the house. USF will match both grants.

Amidst St. Petersburg’s rapid development, Toler stresses the importance of not only the preservation of the Williams House, but of what’s left of historic St. Petersburg.

“You won’t have a reference for what this city was and where it’s coming from and you kind of lose if you lose that history and that reference point,” Toler said.

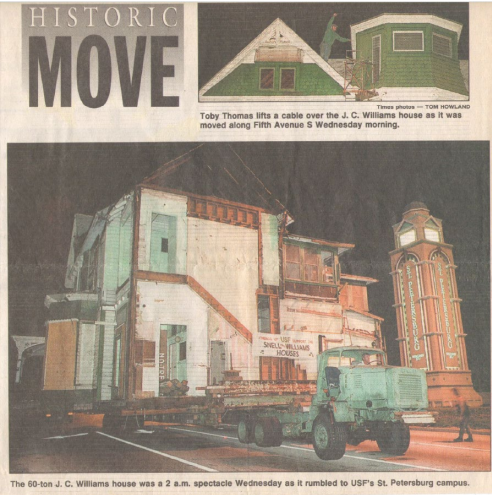

The Historic Williams House was built in 1891 by John C. Williams, the co-founder of St. Petersburg. In 1995, the house was relocated from its original site next to St. Mary’s Church, located at 515 4th St S, to the USF St. Petersburg’s campus.

On the night of Mar. 28 and the early hours of Mar. 29, A crew of contractors from A.B Thomas Housemover placed the Williams House on a flatbed truck and transported the building to its current address, 511 Second Street South.

Contractors rode on top of the house or walked beside it pushing and pulling street signs, lights and tree branches out of the house’s path.

The building was initially used as meeting quarters for faculty and alumni, then housed alumni affairs and university relations faculty

The building is now home to the history and political science department.

“We don’t live in isolation from the past and we certainly contribute to the future. And it’s important that we connect all of those things to be faithful guardians of our planet,” Sudsy Tschiderer said.

Tschiderer, who currently oversees special projects under USF St. Petersburg’s advancement team, works in the Historic Snell House, which was relocated onto campus in 1993.

She witnessed the Williams House being relocated in 1995 and recalled the experience as astonishing and phenomenal.

“If you look around at other universities, many [of them] cherish their history and find ways to incorporate their community history into the fabric of their education. Why should we be any different?” Tschiderer said. “Just because we’re Florida and everybody wants to build concrete on every square inch of land doesn’t mean that we should. What are we sacrificing when we do that? Too much.”