Photo courtesy of sgef_usfsp on Instagram

By Alisha Durosier

An orange blossom, a lightbulb, a butterfly and seashells make up a design that has seamlessly woven itself into the daily backdrop of USF St. Petersburg students.

The design, adorning olive-green T-shirts and posters that have made their way onto bedroom walls, symbolize the campus’ Student Green Energy Fund (SGEF). It also marks an essential step toward one of the organization’s major goals: To create a lasting presence and meaningful impact on the St. Petersburg campus.

Established in 2007, SGEF was created to help reduce USF’s carbon footprint through environmental advocacy and initiatives that promote the use of renewable energy, minimize food waste and reduce greenhouse emissions. Each of the university’s three campuses have a dedicated committee — composed of both students and faculty — that oversee the fund’s usage.

“I’m glad that we’re slowly starting to make our way into people’s lives, even if it’s indirectly, like just sitting in someone’s closet,” said Tori Ursey, SGEF’s director of marketing and communications.

SGEF and all its initiatives are student-funded through a fee of $1 per credit hour billed to every USF St. Petersburg student. Currently with a fund of over $400,000, SGEF is eager to realize its potential.

“We’re just chomping at the bit to use that money,” SGEF’s chair, enviromnental science and policy junior, Oliver Laczko said.

During biweekly meetings, students can propose projects they’d like to see implemented on campus, with the support of SGEF.

Working with SGEF’s proposal advisor, environmental science and policy junior Audrey Everett, students prepare proposals that include elements like a project timeline and budget. They then present their proposal to the SGEF committee and voting members — members who have attended at least five meetings — for feedback or approval.

A major summer task for SGEF was its $100,000 contribution to a USDA Composting and Food Waste Reduction (CFWR) Pilot Project grant. Initially set at $300,000, SGEF’s contribution brought the grant total to $400,000.

The grant will fund the operation of an industrial composter that will be placed behind Osprey Suites. It will also fund internships, student federal work study positions and allow St. Petersburg chemistry professor Dr. John Osegovic to take a semester of leave to help launch and maintain the composter.

SGEF’s contribution not only capped off the grant, but as SGEF’s vice chair and environmental science and policy junior Julianna Parisi notes, it gave the organization the chance “to prove … that we’re serious and that we have money to match.”

Writing the project and grant proposal was a joint effort between Osegovic, St. Petersburg environmental science professor Dr. James Ivey, dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Dr. Susan Toler with support from Everett.

The composter would not only handle food waste produced by The Nest, but also from surrounding businesses, like those who participate in the Saturday Morning Market.

Laczko is confident that they’ll receive the grant.

“And if we do, it’s going to be monumental. It will change the way we handle food waste on this campus,” he said.

Part of the grant money will be allocated to hiring a new sustainability planner to oversee the Office of Sustainability, a position that has been vacant since 2022.

While not their official role, SGEF functions like the campus’ Office of Sustainability. Through initiatives like the composter project, and implementing more on-campus solar carports, SGEF often fills in the gaps left by the vacancy.

Parisi said that the vacancy places students in a unique position, allowing them to gain experience in areas such as grant writing and research. However, she notes that these opportunities combined with their passion for their initiatives can blur the lines between being a student and working a full-time job.

“While I’m meeting with these campus partners, I have to go to chemistry in 30 minutes,” Parisi said. “It’s a work-life balance. You just have to find a way to maintain both.”

With Laczko completing a grant earlier in the semester while Parisi is in the initial stages of writing one, it’s a balancing act well-known by the SGEF committee. Both grants — Laczko’s, submitted to the Tampa Bay Estuary Program and Parisi’s, being prepared for Tampa Bay Water — concern Bayboro Harbor.

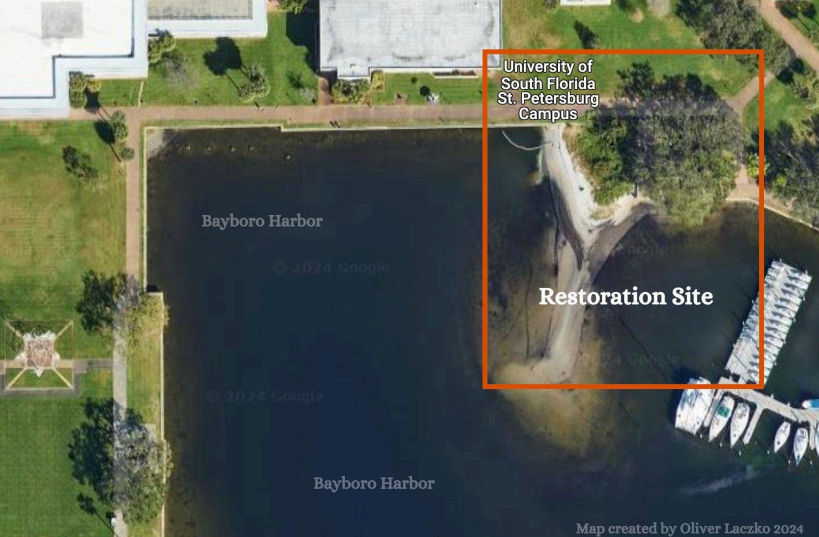

Laczko aims to use the $5,000 grant to tackle the restoration of the harbor’s beach. The beach was left completely exposed following the removal of invasive vegetation and is currently suffering from erosion.

“The goal of the project is to restore a living shoreline to the beach, which is a combination of native vegetation, oyster reefs, and oyster bags that will harbor a lot of biodiversity while also maintaining the sedimentary structure of the beach so that we can continue to reduce erosion,” Laczko said.

His plan includes planting mangroves to help stabilize the sediment and — aligning with the grants theme of public education and involvement — Laczko included a curriculum for on-campus environmental science and biology labs. This curriculum will cover climate change, coastal resilience, green infrastructure and living shorelines.

Photo courtesy of Oliver Laczko

“If we can do the beach restoration project, then I don’t see why we can’t extend that project all the way down the seawall and have a living shoreline of mangroves and oyster reefs … and help protect campus from flooding and storm surge,” Laczko said.

The grant will restore the beach and improve the harbor’s water quality by reducing runoff, water that sits on the surface of the ground instead of soaking into the soil.

The harbor’s water quality, however, is central to Parisi’s research.

Bayboro Harbor suffers a great deal from pollution. One of St. Petersburg’s storm drains is located there, emptying trash, large debris, nutrient and pharmaceutical pollutants, microplastics and heavy metals into Bayboro.

The drain is currently being guarded by a device called a “Watergoat,” floating buoys that skim surfaces of water for trash. However, its current position makes it ineffective and the Watergoat is set to be moved this semester to a more effective location in the Harbor.

Speaking with city officials about the issue, it became apparent to Parisi and Laczko that the harbor’s health wasn’t on the city’s radar.

“They know about Booker Creek. They know about Salt Creek. They don’t know a lot about Bayboro Harbor,” Laczko said.

When Parisi first became SGEF’s vice chair, addressing the issue of the Watergoat was one of her top priorities. Now that the it is being relocated, her focus has shifted to solving the challenges the storm drain poses on the harbor.

“There is not a product that exists that can contain the trash coming out of an underwater storm drain, that powerful. So that’s a problem and I’ve been looking into products,” Parisi said.

Parisi’s research involves studying St. Petersburg’s storm drain map, engaging with campus facilities and city officials, and, of course, researching devices. One option she is exploring is an autonomous device called a WaterShark.

“It’s essentially just a Roomba for the ocean,” Parisi said, collecting trash and pollutants that end up in the harbor.

“I’m excited about everything we’re doing,” Parisi said, recalling all of the ongoing SGEF spearheaded initiatives.

SGEF aims to ensure longevity through not only initiatives, but events and marketing.

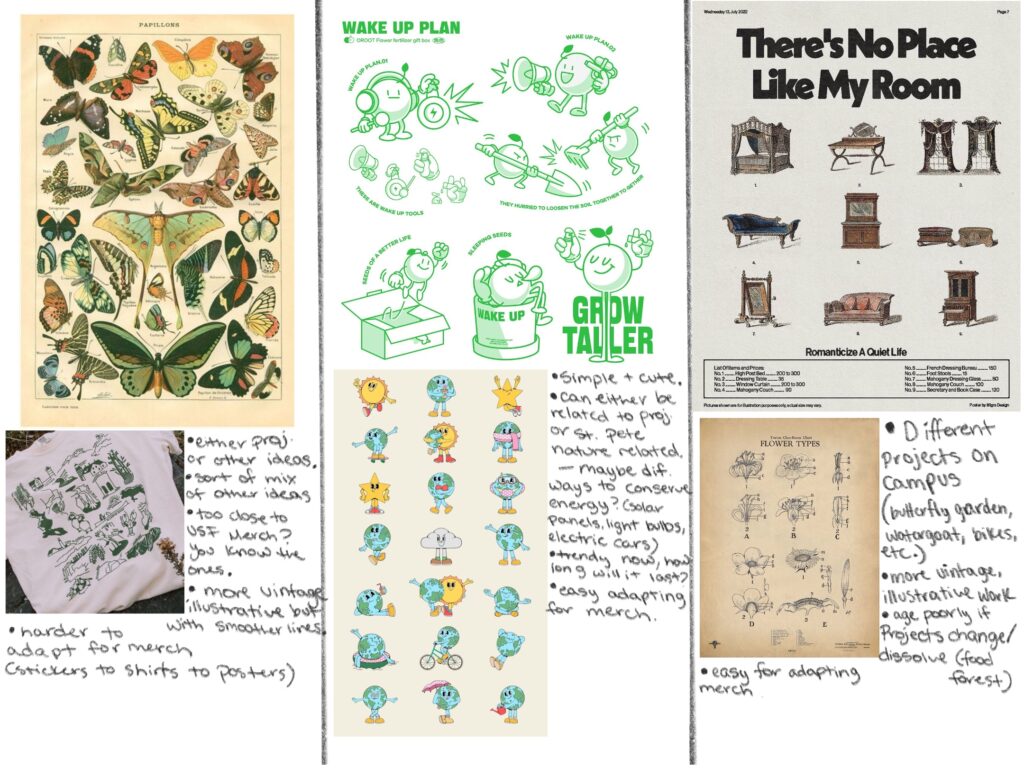

This sentiment played a part in the intent behind the new design.

Creating SGEF-branded merchandise ranked among the committee’s bigger summer tasks, running alongside their work to finalize an initiative to fund a fleet of bikes for St. Petersburg’s Campus Recreation.

Laczko and Parisi accompanied Ursey in a series of discussions and mood boarding sessions along with former SGEF vice-chair Jessie Roguska.

The design is “a weird mix of three,” Ursey, a pre-graphic arts and sustainability studies sophomore, said. It is entirely their original work.

They all agreed to knit together the styles of vintage science textbook illustrations, something simple, reminiscent of the SGEF logo, and a structured, numbered look much like a diagram. Thus, the design was born and SGEF became a watermark on students’ day-to-day on campus.

The design made its first impression on the campus’ culture in August at Get on Board Day, printed on 100% cotton, sustainably manufactured and transported T-shirts and wildflower seed paper.

“I’m really proud that we got SGEFs name out there,” Laczko said. It was a T-shirt that led Laczko to an SGEF hosted event his freshman year, that ultimately ushered him into the position he occupies currently.

“There are freshmen now that will have our shirt until they graduate, and people will recognize SGEF, whether you’re a returner or a newcomer to campus, for the foreseeable future. And that is really important,” Laczko said. “Students should know of the opportunity to utilize the funds that they pay for.”

In creating longevity for the organization, Laczko also desires to leave SGEF’s future leaders a paper trail.

“I certainly don’t want to leave the future leaders of SGEF without any sort of blueprint. So, for starters, I document everything,” Laczko said.

In collaboration with the library, SGEF is working to archive all of their recorded general body meetings, proposals, grants and initiatives.

“I want them to know that the problems you’re seeing, we see. And we’re trying to do something about it. And it’s just a very slow process, unfortunately,” Laczko said. “But we’re trying to build something that’s going to outlast our time at USF and hopefully better it for the future.”

SGEF holds biweekly meetings in SLC 2100. Students can stay updated through their Instagram, @sgef_usfsp.