As one of their first meetings, the African American Burial Grounds and Remembering Project team walked along Tropicana Field’s parking lot one and underneath Interstate 175.

Photo courtesy of the African American Burial Grounds and Remembering Project

By Alisha Durosier

Barely able to hear themselves speak, a group of academics and students stood underneath Interstate 175’s overpass across from Tropicana Field’s parking lot one. As cars zipped above them, they were grappling with the reality of what they were standing on.

Beneath their feet were two cemeteries, Moffett and Evergreen. Across from them, underneath parking lot one, was another: Oaklawn. The cemeteries were established between 1888 and 1907 and serviced the surrounding African American community until 1926 when they closed.

USF faculty, students and volunteers took the constant buzz of cars as motivation. It was a reminder of all the history that had been wiped from the area and since forgotten.

“There were people and families and histories that no one was talking about or really understood,” said USF anthropology chair Antoinette Jackson.

“People were going over the overpass, not having any idea that there was a cemetery right here,” she said.

The group’s walk across Tropicana Field’s parking lot and underneath the overpass was one of the budding moments of the African American Burial Grounds and Remembering Project (AABGRP).

Under USF’s Living Heritage Institute, the ongoing multi-campus, multidisciplinary initiative was the fruit of a $500,000 grant from the university. Distributed across 23 university-wide projects, all of which focus on racial disparities in the Tampa Bay region, the grant was part of USF’s 2020 anti-racism efforts.

Spearheaded by Jackson, the AABGRP confronts the erasure and neglect of Black cemeteries across Tampa Bay using a combination of ethnographic research methods, like interviews and genealogy and art.

According to USF anthropology doctoral student and AABGRP research associate Kaleigh Hoyt, the project’s goal is to fill in the gaps found in historical records.

To that end, the project brought together “a group of people who came from a variety of backgrounds and each brought a really unique set of skills and tools to assist in filling the record and to tell that story,” Hoyt said.

Specifically in Florida, desecrated Black cemeteries are being discovered at an astonishing rate.

Currently, the project focuses on four burial grounds.

Zion, Tampa’s first all-Black cemetery, was discovered underneath land that now supports Robles Park Village public housing complex and a towing company.

In 2019, at least 200 graves were estimated to be underneath the property using ground penetrating radar (GPR).

“Zion Cemetery really was a catalyst for the conversation,” Hoyt said, citing the 2019 Tampa Bay Times article discovering Zion Cemetery, which sparked curiosity around forgotten and neglected cemeteries in Tampa Bay.

Photo courtesy of Cardno

Evergreen, Oaklawn and Moffett cemeteries are concentrated near Tropicana Field in St. Petersburg.

The latter was initially reserved only for Civil War veterans, and later used for African American burials. Evergreen was a designated African American cemetery, and Oaklawn was segregated.

“We wanted to understand the process by which these cemeteries had gotten erased in the first place,” Jackson said. “Erased in historical records or erased in legislation or [in] people’s memory.”

Photo courtesy of the African American Burial Grounds and Remembering Project

According to the project’s research, in February 1926 the three St. Petersburg burial sites were closed and condemned in compliance with a city ordinance which cited “public health concerns” as the reason.

A month later in March, the city announced its plans to extend Fifth Avenue S. through Moffett and Evergreen.

Later that month, another city ordinance called for the reinterment of the cemeteries’ remains. Relocation was based on race; white graves were moved to Royal Palm Cemetery and Black graves were moved to the Lincoln Cemetery.

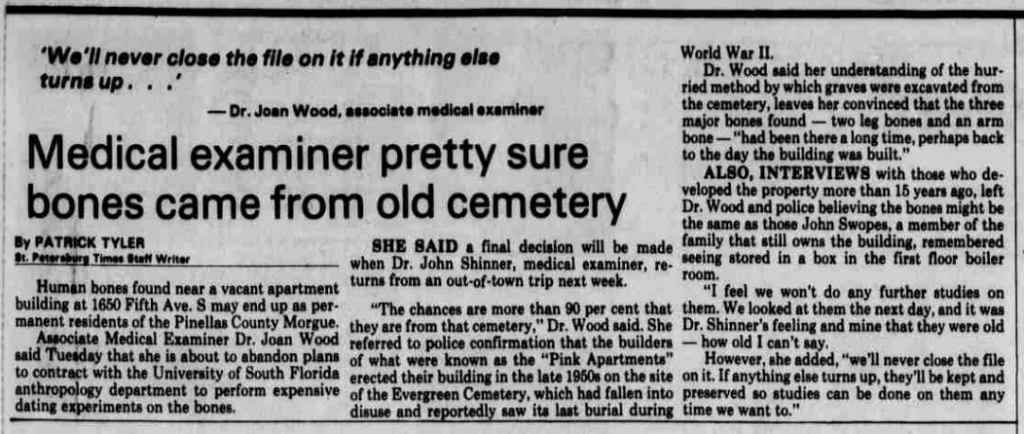

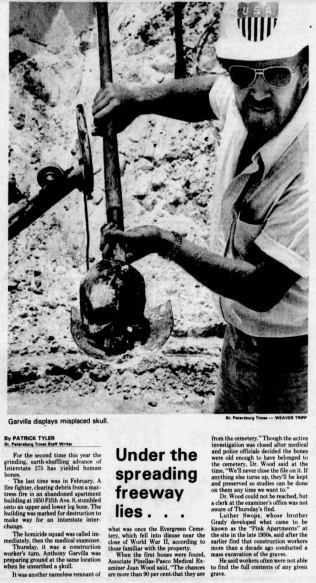

Since then, as the landscape of St. Petersburg began changing through construction and redevelopment projects; it was evident that not all remains were properly reinterred. Throughout the 1970s and 80s human remains, headstones and coffins were repeatedly found on I-175’s construction site, by vacant apartment complexes and in other areas near the Moffett and Evergreen sites.

The recent decades’ resurfacing evidence of graves in the area even prompted concerns in 1990 when the African American housing project, Laurel Park, was set to be demolished and replaced by what is now Tropicana Field’s parking lot one. Laurel Park was built on the Oaklawn site in the 1940s.

City officials, who said they were not aware the land was once a cemetery, were fearful of finding remains, which would halt the project.

Gerald Metko was the executive director of the St. Petersburg Housing Authority when Laurel Park was bought from private developers in the 1960s. In 1990 he told St. Petersburg Times (now Tampa Bay Times) “when we acquired the property, some of the old-timers on staff told me that most of the graves were moved, but there were some that were not.”

Learning that decision makers were aware of the cemeteries and the rushed attempt or non-attempt to properly reinter the buried bodies, was the most frustrating part of research for Jackson.

“The farther we get from the decision-making process, it all seems like people didn’t know,” Jackson said. “But once we started going through the layers, there were decisions made at every level and proof through the newspaper clippings, through the archival information, through the oral history records, that these decisions were made with an understanding that there were cemeteries there and they might have said they moved the bodies, [and] they did whatever.”

In the case of Zion Cemetery in Tampa, developers plucked off the headstones of graves buried 4 to 6 feet underground, before developing on top of the burial ground in 1929. In the early 1950s, when three caskets were found during the construction of Robles Park Village, the city of Tampa told press that the cemetery’s graves were reinterred in 1925.

“It’s an egregious and explicit act of not just erasure, but an act conducted with such depravity,” Hoyt said.

In 2021 archaeologists who surveyed Tropicana Field’s parking lot one using GPR, reported finding three graves. In July, the grounds were surveyed again by archaeologists who said that further investigation was required to confirm if there are still graves underneath the lot due to the burial ground’s extreme level of disturbance.

In the following months, the archaeologists, who work under engineering, architecture and environmental consulting firm, Stantec, reported that their team “identified several areas of anomalies that could be related to historic burials or cemetery features.”

The 86-acres in the heart of St. Petersburg, including the Tropicana Field site, is also known as the Historic Gas Plant District. To the AABGRP team, it was apparent that the cemeteries and the surrounding community — the Gas Plant District — were inextricably linked.

Photo courtesy of St. Petersburg Times (now known as Tampa Bay Times) (1979)

“The notion of forgotten cemeteries is also akin to forgotten histories or forgotten communities,” Hoyt said. “When we started with the burial ground project, it took probably a span of three weeks for the project team to all agree that it had become abundantly clear that there was absolutely no way to tell the story of the cemeteries, Oaklawn, Evergreen and Moffett without also telling and sharing some of the history of the Gas Plant District.”

This mutual understanding changed the scope and trajectory of the project. The team wanted the project to also engage with the Gas Plant District’s history. Especially during a time when the initial talks of Tropicana Field’s redevelopment were starting to take place.

The construction of the interstate and Tropicana Field, initially known as the Florida Suncoast Dome, is what ultimately displaced Gas Plant District residents. Promises of new job opportunities, an industrial park, and affordable housing were not met, while homes, businesses and churches were demolished or relocated to make room for the dome.

New research questions emerged: “What was the community like? Who were the people in the communities?” Jackson said tying in the history of the Gas Plant District was aimed “to give people more of a sense of the living and the life that surrounded the people who may have been buried there.”

“If you talk to local residents who are part of the same communities that we’re talking about,” Hoyt said. “They will tell you that they absolutely are not forgotten and that they were in fact, taken, on behalf of false promises, on behalf of zoning grades assigned to them and on behalf of structural decisions by government or city officials to construct things like the federal highway system.”

This is where oral history comes in.

Along with people with some connection to the cemeteries — like descendants of people who were buried there — the project team also spoke with residents of the Gas Plant District, who detailed their experience living in the community.

Seventy-five-year-old local historian and president of the African American Heritage Association Gwendolyn Reese, grew up in the Gas Plant District, and also participated in the AABGRP as an interviewee.

“All my memories are fond and so it’s a little disconcerting for me when I hear negatives about the area. As a child growing up, it was a wonderful place to be. There was safety there. It was a community. We knew each other, almost everybody knew everybody. It was a haven, a safe haven from the racism that existed outside of our neighborhood,” Reese told The Crow’s Nest.

Reese described a close-knit mixed income neighborhood. Her family and her neighbors didn’t lock their doors, she lived across from her high school principal and walked to school with her librarian.

Due to redlining, residents of the Gas Plant District were forced to live in the same neighborhood, “but it made for a very empathizing, private community,” Reese said. “We could actually get a lot of the services we wanted within our own neighborhood. And there, of course, we received respect and we were valued.”

Reese’s family moved out of the neighborhood after her formative years, but the Gas Plant neighborhood remained her community up until its displacement.

“Looking at a baseball stadium replacing what once was a thriving community was not a positive currency,” Reese said. “It was supposed to provide employment and housing. And then within just a couple of years, it changed. For us to give up our community, I’m not sure we would have done that for baseball.”

What links these cemeteries to the Gas Plant District is, of course, location. However, this historic Black neighborhood and these cemeteries experienced similar patterns of erasure.

“Out of the project, it became very apparent that the issue of Black cemetery erasure in the Tampa Bay area was not only exacerbated or far bigger than anyone would have expected locally, but that the issue was actually pervasive nationwide,” Hoyt said.

People across the nation with similar initiatives advocating for neglected historical Black cemeteries, began reaching out to Jackson. The team saw that most of the nationwide initiatives seemingly operated in isolation and Jackson wanted to connect them. The Black Cemetery Network (BCN) is a collaboration between nationwide Black cemetery initiatives and advocates. Jackson is BCN’s director and Hoyt, the creative director.

There are over 180 burial grounds registered under BCN, all arranged on an interactive map.

“It was a way to showcase that this was more than just a Florida issue,” Jackson said.

The efforts to bring forgotten histories to the forefront, has not gone unnoticed. AABGRP and BCN are both ongoing, with the projects increasingly gaining visibility as they age.

Reese, also a part of the recent Tropicana Field’s and Historic Gas Plant District redevelopment team, says that she is here to keep history in a place where everyone can see and “to make sure that that history is interwoven in everything that’s done,” Reese said.

“We cannot forget,” Reese said. “We cannot let them forget.”