Photo by Mahika Kukday | The Crow’s Nest

By Mahika Kukday

I could never fully get behind baguettes.

This wasn’t great for the French-girl aesthetic I was desperately trying to achieve in 2021. To my father’s dismay, there are no photos of me crossing the street holding a brown paper bag full of baguettes.

What a waste of two years in Paris, right?

Trying to chew them gave me a genuine headache, and sandwiches, gosh, it would actually save time if I took all the fillings out and dumped them on my plate beforehand. The crusty bread was going to squeeze them all out anyway.

Enter: Vietnam.

French colonists brought their crusty headache-inducing bread to Vietnam in the 19th century, The Hanoi Times said, when wheat was imported and its products were reserved for the colonial elites. But after World War II disrupted trade operations, wheat, and by extension, baguettes, became cheaper and widely available.

In the late 1950s, Vietnam did the world a culinary favor and coined bánh mì: the baguette sandwich to end all baguette sandwiches.

While it’s highly customizable, the most iconic banh mi iteration is one with pork belly, sour pickled daikon, fresh herbs and a characteristic smear of pâté.

Literally translating to “paste,” – and get ready to ridicule the French again – pâté is a spreadable filling made of meat and fat baked in a loaf-shaped pan. It’s unbelievably rich, savory and comes in various delightful versions, such as chicken-liver pâté.

I’ve found that a bánh mì baguette is still crusty on the outside, but with a more airy and soft interior as compared to its French jawbreaker ancestor. One side gets a smear of pâté while the other gets mayo, and then you layer in your pickled veggies, meat, cilantro and sliced jalapeños.

Mahika Kukday | The Crow’s Nest

That’s why bánh mì works. It’s got the crunch, the bite, the melt-in-your-mouth meat. And it backs it up with the same balance in flavors: sour pickled veg, fresh herbs, usually some sweet/sour meat, salty pâté. It’s just so well done.

I walked 30 minutes in Lincoln, Neb. to get the bánh mì in that photo.

You read that right.

Lincoln is about as Midwest college town as you can get. There’s pretty much nothing to do unless your life starts and ends with the University of Nebraska-Lincoln (UNL) Huskers and it reaches borderline Antarctic temperatures.

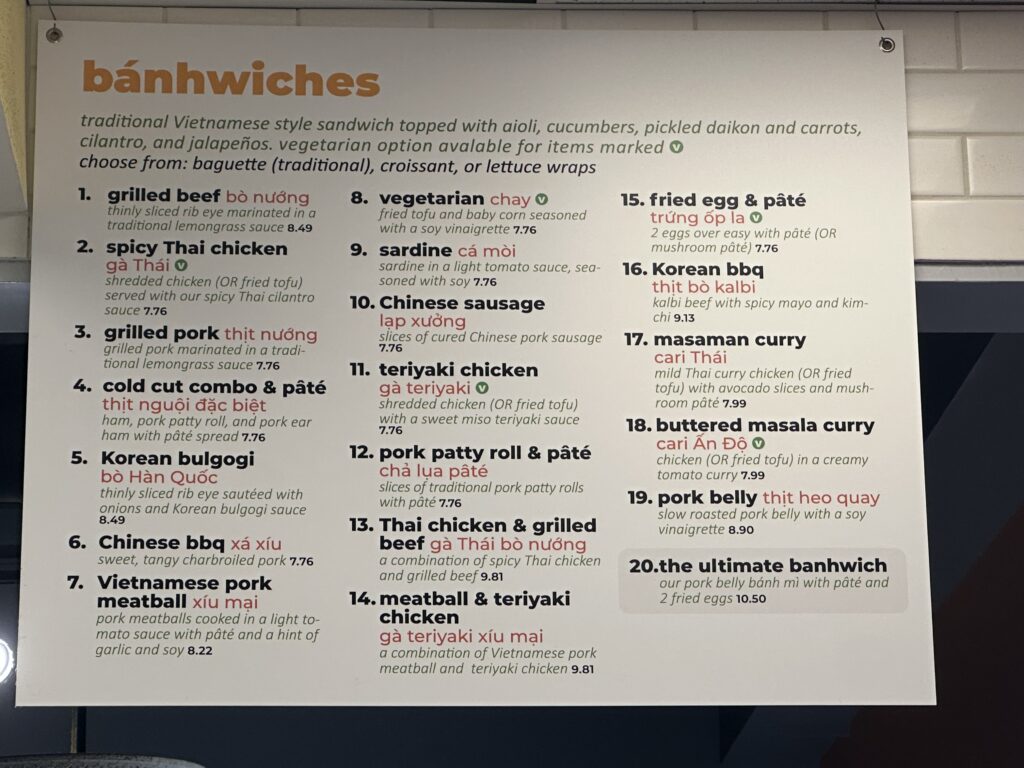

My boyfriend recently graduated from UNL, and every hurricane season, I’d flee Florida and seek refuge at his Lincoln apartment. Last May, as he studied for his finals, I stalked Google Maps and found Banhwich Café.

Photo by Mahika Kukday | The Crow’s Nest

It’s one of those meals that transports me straight back to a certain point in time. Banh mi immediately transports me to the haze of October 2024.

I was in Lincoln because Hurricane Milton rendered my dorm uninhabitable, and I used a weekend b bánh mì to motivate myself through a week of online class where I couldn’t tell what day it was.

Which brings me to my other big takeaway of “The Great Mental Hurricane Fog of 2024.” Pelican Apartments’ students, unable to enter their rooms for three weeks, stayed evacuated all over the country and shifted to online school.

Professors were technically mandated to be flexible, but my interactions with them during this time taught me some hard less.

It’s important to know I’m Indian and received an Indian secondary education. I’m extremely used to strict grading, harsh feedback and deadlines and no babying. In fact, in many ways, I think the American education system could greatly benefit from some good old Asian scolding.

But I want to make one thing clear: if you’re interested in exercising your authority more than helping your students grow, being a professor isn’t the job for you.

Professors will often cite “unfair treatment” as the reason for not granting case-by-case extensions, but I argue that the premise of treating all students equally to a fault is flawed.

For many, college is the most transformative period of people’s lives. It’s no small feat to manage personal, mental, physical and professional success on one’s own for the first time.

College is touted as the pinnacle of self-development and introspection, but with that comes a slew of challenges that are unique to everyone, especially during the aftermath of two hurricanes.

I’ve had professors reply to essay-like emails where I explained the details of a serious family emergency (back in India, mind you) with zero empathy or even acknowledgement of my situation, just a simple “no extension granted” message.

There is absolutely no situation where an educator’s desire to be “respected” trumps their duty to treat students as real people. Especially when professors have the power to change lives.

Dr. Luis Felipe Mantilla and Dr. Arturo Jimenez-Bacardi taught the first political science classes I ever took. It’s now my minor, because they treated me like a real person, and cared more about imparting their wealth of knowledge than trivial displays of authority.

When I missed three classes in a row because of the same personal crisis, Dr. Mantilla emailed me to say that he noticed my unusual absence and asked if he could offer me any university resources.

They changed my opinion of political science like the banh mi changed my opinion of the baguette.

Luckily for college professors, one good bánh mì will likely leave a much more long-lasting impression than a dozen crusty baguettes.