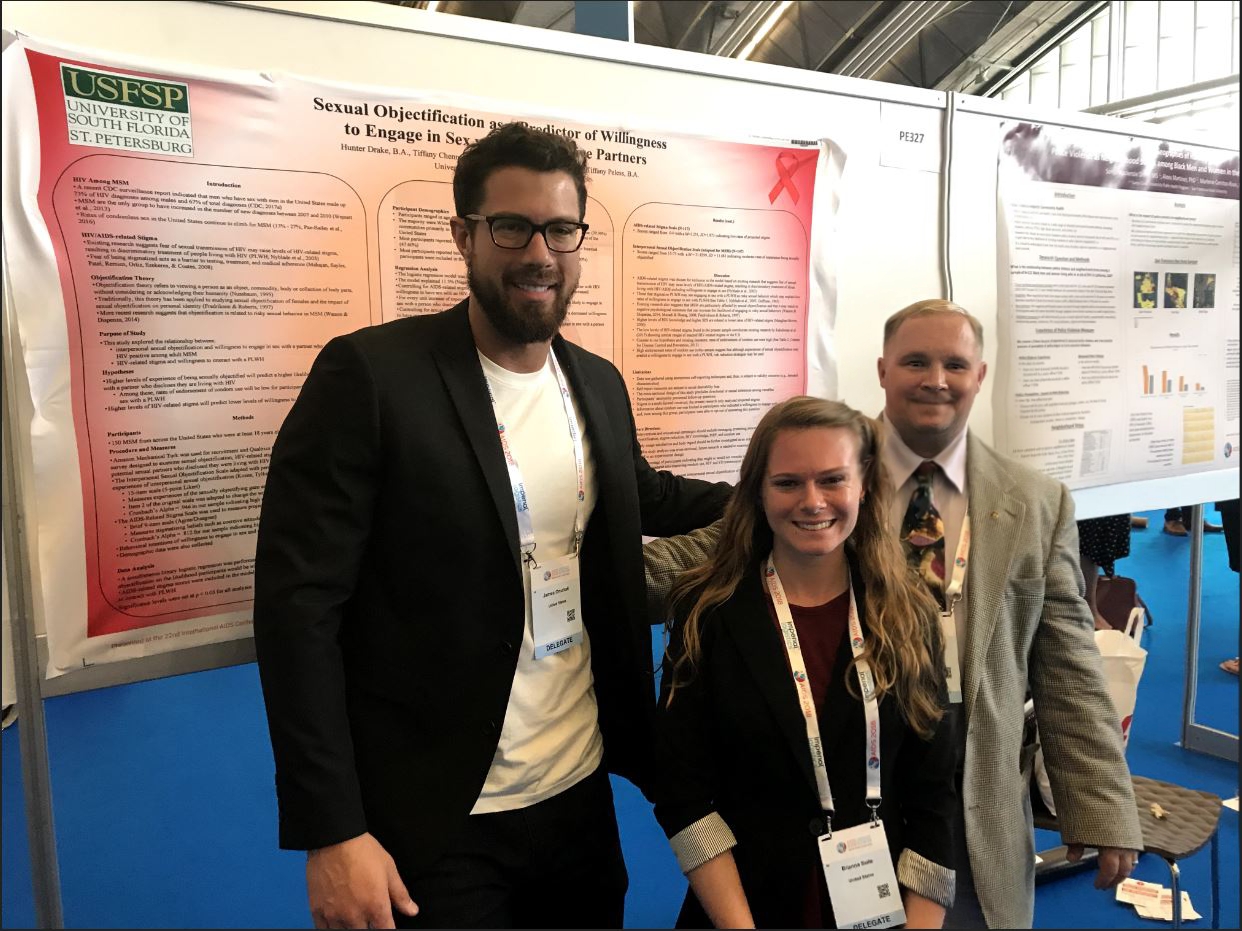

Hunter Drake, right, presented in July his research with the help of James Onufrak and Brianna Suite at the 2018 International AIDS Conference in Amsterdam. Drake’s abstract was about how objectification affects whether men have sex with HIV-positive men. Courtesy of Bryan A. Kutner

By Emily Wunderlich

Hunter Drake is not afraid to disclose that he is HIV-positive.

In the 20 years since his diagnosis, Drake, an experimental psychology graduate student, says entire rooms of people have cleared out once they discovered his status.

“How do you re-humanize people? Since I’ve been so open about it, will it change how people treat me?” He asked. “At every turn, you’ve got to tell your story … It fights stigma to say hello.”

In July, Drake and two other graduate students represented USF St. Petersburg at the 2018 International AIDS Conference in Amsterdam.

Drake, with the assistance of Brianna Suite and James Onufrak, both experimental psychology graduate students, presented the effects of sexual objectification on men’s willingness to have sex with HIV-positive men.

“I’ve always been looking for obscure, unstudied factors,” Drake said. “(Objectification is) a factor in body image issues for women and many psychological risky behaviors in women. But it’s not been studied in men, and if you learn anything in a psychology course here at USFSP, you learn that we’re not that different.”

Drake used an information-gathering site to collect nationwide questionnaire data from 150 men over the age of 18 who have sex with men. He found that for every unit increase in sexual objectification, people were 6 percent more likely to sleep with someone who is HIV positive.

However, he said, that should be taken in context with the intentions to be safe during sex. Overall, the people were much more likely to be safe than other previous literature had indicated.

Every year, the International AIDS Conference covers a variety of topics through performance and concept art, from epidemiology and sex worker research to harm reduction in intravenous drug users.

“If you didn’t leave changed, you’re not human,” Drake said.

In one particular exercise, participants went through a simulation in which a doctor diagnosed them with HIV.

“He says, you know, ‘Unfortunately, I have to tell you you’re (HIV) positive, and I need you to look at me in the eye and I need you to repeat after me: I,’ and then he says your name, ‘am HIV positive,’” Drake recalled.

“I tell everybody, but I’ve never once put my name beside that phrase,” he said. “I got like halfway through the phrase and choked up.”

Drake called it the “longest fifteen minutes” of his life.

Onufrak said the conference showed him how often people discriminate others without realizing it and he learned how to be more empathetic toward others.

“I was surprised by how much progress still needed to be made in many different areas regarding equality,” he said. “While it was impressive how much attention this issue has received, there is still a lot of progress that needs to be made, especially in certain locations and within certain demographics.”

At the conference, Drake, Suite and Onufrak recorded a podcast of their presentation on

Radio Amsterdam for people who could not attend. Drake also said actress Charlize Theron and Bill Clinton made appearances.

But the most rewarding part, he said, was coming away from it knowing you’re not alone.

How it began

Drake’s abstract at the conference stemmed from his graduate thesis at USF St. Petersburg, which explored how meeting online versus in person affects people’s willingness to have sex with HIV-positive partners.

“Venue matters specifically for people encountering people who are HIV-positive,” Drake said.

For people who met in person, they were less likely to have sex with a partner who disclosed they were HIV positive. People who met online were more likely to have sex with an HIV-positive partner.

“That may be because you’re sitting across from them in a public space and other people might see you talking to someone that they know is HIV positive, and so you’re less likely to engage with that person,” Drake said. “When you’re online, you’ve got that sense of privacy that nobody knows what you’re doing and people are more willing to be risky there.”

What troubled Drake most was that when people didn’t disclose their HIV status, potential sexual partners just assumed they were negative.

“It’s everybody’s responsibility to take care of their own health. You should ask, and people should tell,” he said.

Aside from Suite and Onufrak, Drake credited Tiffany Chenneville, associate professor of psychology, with his success.

Drake said Chenneville, who holds a doctorate in school psychology, attends the conference almost every time she publishes a paper.

But this year, Drake, Suite and Onufrak went in her place on a scholarship from the International AIDS Society.

“They paid for everything, except I refused the (hostel),” Drake said. “You’re traveling to another country, you’ve got to have your own bathroom.”

According to Drake, anybody can request to go, but their abstract must be accepted.

“If anything, what I took away from the conference was just more empathy and more passion,” Drake said.

Drake encouraged students to get more involved in their areas of study by finding a professor who shares similar interests and assisting their research through labs, experiments and literature reviews.

“I’ve been here four years,” he said. “When I first got here, people were really interested in helping out in labs. People were really interested in doing their own research. Now, if you’re not in an honors thesis class, nobody’s doing it.”