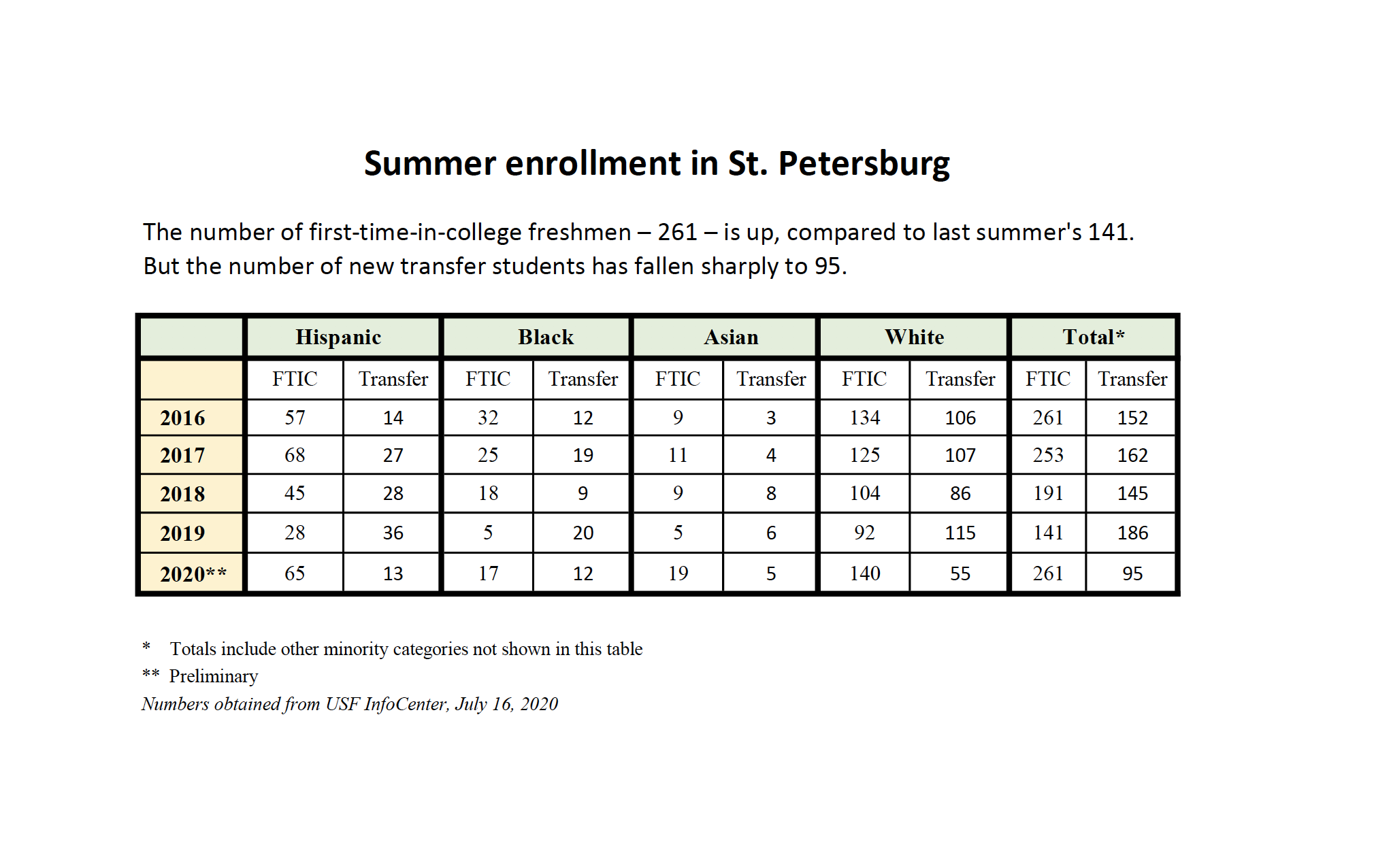

Pictured Above: The chart above outlines changes in summer enrollment at USF St. Petersburg since 2016.

Courtesy of Matt McCann

By Nancy McCann

Summer enrollment of new freshmen at USF St. Petersburg is up this year, but the number of new transfer students has plunged.

For the first time in at least 10 years, the total of all levels of transfer students starting at the St. Petersburg campus in the summer is significantly lower than the year before — from 186 in 2019 to 95 this year, a decline of about 50 percent.

The dramatic drop in the number of St. Petersburg’s new transfer students goes along with a sudden turnaround in the number of first-time-in-college (FTIC) freshmen.

St. Petersburg’s application and enrollment numbers have been watched closely since the campus began raising some of its admission requirements two years ago to be consistent with Tampa’s and comply with the conditions of consolidation, which began July 1.

The number of FTIC applications and enrollments plummeted, so the significant increase in new freshmen this summer is a welcome development.

But until this summer, the number of new transfer students had held steady.

Glen Besterfield, USF’s dean of admissions, attributes the decline in transfer students to “more rigorous transfer requirements in the natural science and business degrees.”

Transfer student “admits are significantly down” across all three campuses, Besterfield said in an email to The Crow’s Nest. “Depending on whether a student is a lower-level, mid-level or upper level transfer, USF is now enforcing pre-requisite courses for admission.”

Besterfield said the new requirements had “an immediate impact but (the numbers) should rebound in future semesters” as students complete the required courses in the community college system or other institutions.

In contrast, summer enrollment of new freshmen has rebounded after a two-year decline, which began after St. Petersburg started to raise its admissions requirements early in 2018.

Following a 25 percent drop in FTIC summer enrollment from 2017 to 2018, and another 26 percent drop from 2018 to 2019, there is an 85 percent jump in 2020 — going from 141 to 261 new freshmen.

The explanation: A substantial number of students who originally applied to the Tampa campus were sent to St. Petersburg.

“In early 2020, a decision was made to move 300+ summer admits who applied to Tampa to SP (St. Petersburg) to start their collegiate career, because Tampa would hit capacity for summer FTIC admits,” Besterfield told The Crow’s Nest in an email.

According to Regional Chancellor Martin Tadlock, 109 of the “admits” who were moved to St. Petersburg enrolled in classes this summer.

Without these students from Tampa, St. Petersburg’s summer enrollment would have been about the same as in 2019, a steep drop from 2017.

Ray Arsenault, history professor and then-president of the St. Petersburg Faculty Senate, called last year’s low FTIC enrollment numbers “catastrophic.”

University leaders in Tampa and St. Petersburg responded to concerns about sinking FTIC enrollment by noting various other pathways to the USF campuses, especially starting as a transfer student from the community college system.

But now the number of new summer transfer students is cut in half.

In the summer of 2018, transfer students made up 43 percent of all new students enrolled in St. Petersburg. That went up to 56 percent in 2019. Now, it’s 27 percent in 2020.

When asked what’s being done to build transfer student numbers back up, Tadlock told The Crow’s Nest that there is continuing emphasis on two programs that provide “seamless transfer” from St. Petersburg College to USF St. Petersburg: PATHe and FUSE.

PATHe, which stands for Pinellas Access to Higher Education, is a partnership between St. Petersburg College and USF St. Petersburg that was founded in 2018. FUSE is a partnership between USF and eight Florida community colleges for specific majors.

Tadlock said with consolidation of the three campuses, other two-year colleges that are partners with Tampa in the FUSE program can set their sights on St. Petersburg.

“Enrollment in the state’s two-year colleges is down and has been for two years in a row,” he added, so transfer numbers from those institutions are down as well.

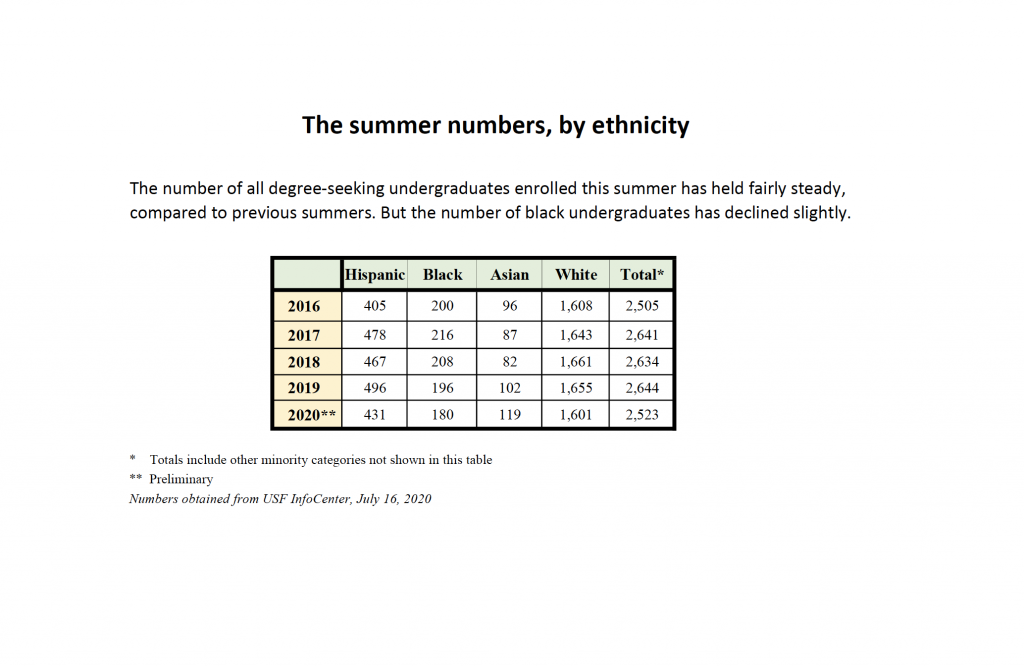

Even with the dips in the number of FTIC freshmen and new transfer students since 2018, the total number of all degree-seeking undergraduates enrolled at USF St. Petersburg is only 4.6 percent lower this summer compared to 2019.

Tadlock said although there have been recent declines in the number of new students, retention rates are increasing.

“Our number of returning students has continued to climb, which is reflected in the total numbers,” he said. “People are staying with us to complete their degree more now than ever before.”

Black enrollment remains low

The number of black students remains a concern, however.

One of the St. Petersburg community’s earliest concerns about consolidation of the three campuses was the impact it would have on the minority student population.

Compared to the summer of 2016, St. Petersburg’s low summer enrollment in 2019 represented an 84 percent drop in the number of FTIC black students; a 51 percent drop for Hispanic students; a 44 percent drop for Asian students; and a 31 percent drop for white students.

The summer numbers are up from 2019 to 2020, going from 5 to 17 FTIC black students; 28 to 65 Hispanic students; 5 to 19 Asian students and 92 to 140 white students.

But even with the large percentage increases this year, the number of new black freshmen this summer is down by about half from 2016.

For decades, St. Petersburg took pride in being a campus that embraced non-traditional and minority students, especially students who lived in Pinellas County.

If those students had borderline high school scores, wanted to experiment and change majors, and took longer to earn their degrees, that was acceptable.

But with single accreditation, the St. Petersburg campus must soon meet certain metrics in student admission requirements, retention and graduation rates, research spending, and other academic yardsticks.

Those are the metrics that enabled USF Tampa to become one of three preeminent research institutions in the state university system in 2018. Keeping that distinction after consolidation is a top priority of Tampa administrators and the university’s Board of Trustees.

Besterfield, the dean of admissions, said in December that the three USF campuses do not admit freshmen with a weighted high school GPA below 3.0 (with exceptions in areas like athletics, dance and theater), which is tougher than St. Petersburg’s prior admissions practices.

“They were admitting students in St. Pete with very low (high school) GPAs,” he said. “There are other ways to go. We guarantee admission with an A.A.”

In addition to raising the GPA threshold, St. Petersburg was forced to rapidly raise its targeted student profile, the average GPA and average standardized test score of the freshmen it admits.

As the student profile went up, the percentage of black new freshmen fell the most.

Out of all the degree-seeking undergraduates attending the St. Petersburg campus this summer — new and continuing — 7 percent are black; 17 percent are Hispanic; 5 percent are Asian; and 63 percent are white.

Since summer 2016, the number of total black undergraduates seeking degrees has fallen by 10 percent, from 200 to 180.

Some people contend that the university can do better.

The Tampa Bay Times reported July 13 that protests against racial inequality experienced by students were in their eighth week at USF Tampa, “while the Black Student Union and at least three faculty groups have sent letters to USF President Steve Currall with urgent calls to rid campuses of systemic racism.”

One suggestion from some of the protesters, according to the Times, is that the university drop test scores (SAT or ACT) from the application process because “those exams do not reflect the talents and abilities of students across the socioeconomic spectrum.”

A new task force on inclusivity and diversity at the St. Petersburg campus met for the first time on July 7. The meeting was not open to the public.

The next meeting is scheduled at 1 p.m. on Aug 4. Caryn Nesmith, special projects manager in the regional chancellor’s office, said the task force meetings are “work meetings” that are not required to include the public, and she can be contacted at carynn@usf.edu for more information. (See agenda for list of task force members.)

Paired courses and higher tuition

Almost all of the first-time-in-college freshmen at the St. Petersburg campus this summer are involved in something called the Summer Institute.

The institute is “an outstanding, new experience for our incoming summer FTIC students,” wrote Kathleen Gibson-Dee, chancellor’s assistant for strategic initiatives in St. Petersburg, in an email to The Crow’s Nest.

She said each student is enrolled in a pair of general education courses with the same group of students.

“Learning in a cohort fosters a sense of community and belonging, providing students opportunities to make friends and connections in their shared classes,” Gibson-Dee said.

The pairs of classes, like Introductory Statistics and Environmental Science, have “connecting themes” and “synergy” in the assignments, she said, and the courses are linked with programs for “social, financial, intellectual, physical, emotional/spiritual, and environmental aspects of wellness.”

There are 224 students in the Summer Institute, Gibson-Dee said.

Like other classes this summer, the paired courses are online.

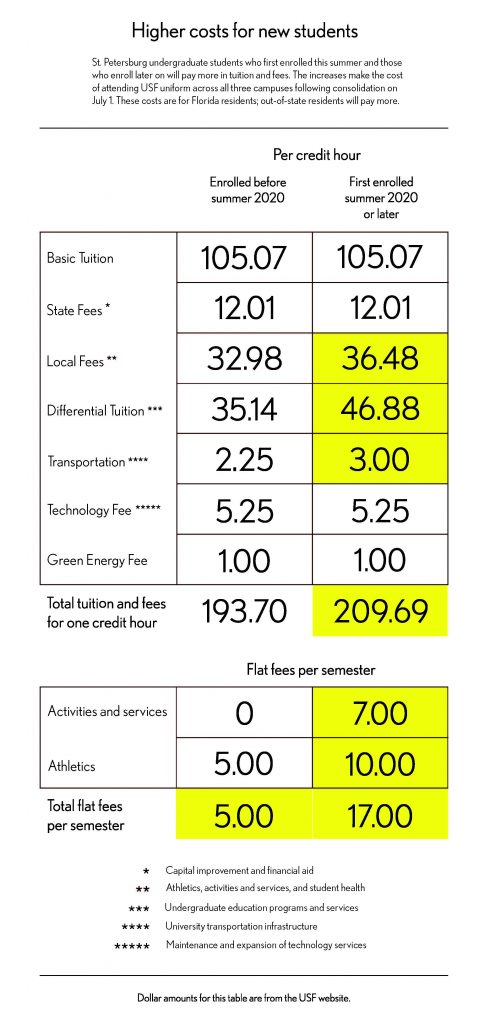

The first-time freshmen and new transfer students at the St. Petersburg campus this summer are paying higher tuition and fees than continuing students.

On June 2, the USF Board of Trustees approved a single rate of tuition and fees for all three campuses to prepare for operating as a singly accredited university, which began on July 1.

The total increase for the semester for a new undergraduate in St. Petersburg taking 12 credit hours is $203.88.

The tuition and fees for one undergraduate credit hour went up by a total of $15.99 — from $193.70 to $209.69 — and total flat fees for the semester rose by $12.

The basic tuition of $105.07 per credit hour remained the same. Local fees for athletics, activities and services, and student health increased by $3.50 per credit hour; by $0.75 for transportation infrastructure; and by $11.74 for a category called differential tuition.

Florida law says differential tuition is for “improvements in the quality of undergraduate education” and financial aid to undergraduates. The list of uses for these funds includes “increasing course offerings, improving graduation rates, decreasing student-faculty ratios, and providing salary increases for faculty who have a history of excellent teaching in undergraduate courses.”

Differential tuition was created in June 2007 for Florida’s five public research universities – USF, University of Florida, Florida State, University of Central Florida and Florida International — according to USF’s website.

The law says beginning July 1, 2014, only research universities designated as preeminent could establish or increase differential tuition.

The $12 increase in flat fees per semester for activities and services, and athletics, is in addition to the per credit hour charges for these same areas.

Students who enrolled before summer 2020 will pay the tuition and fees that were in effect when they were originally admitted until they graduate, if they remain continuously enrolled at the university and graduate by December 2023.