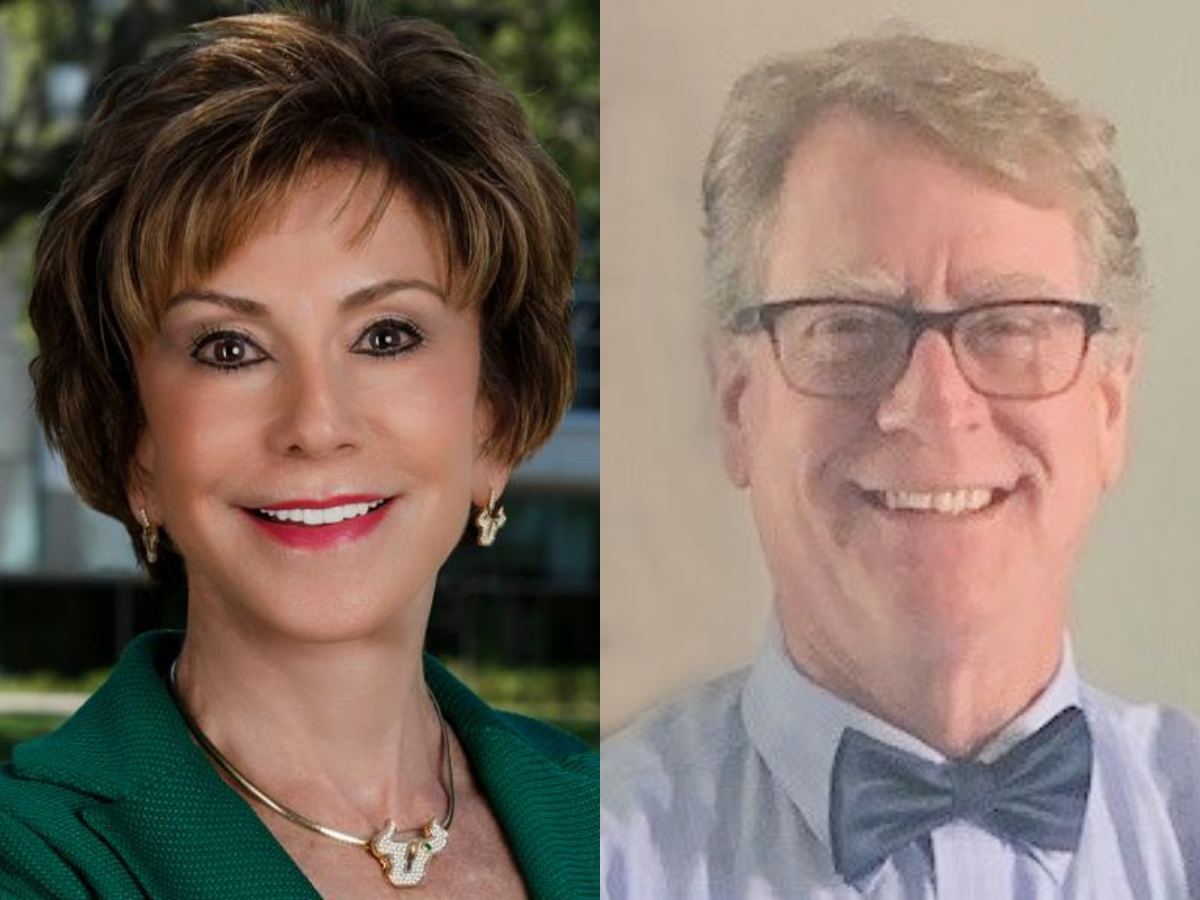

Pictured above: Under then-President Judy Genshaft (left), USF spent heavily to boost its metrics and national rankings. The Faculty Senate, led by Tim Boaz, spent months challenging the administration’s budget strategy to pay for it.

Courtesy of USF and Tim Boaz

By Nancy McCann

For years, as USF pushed relentlessly to become a state “preeminent research university” and pull up its national rankings, it spent millions of dollars to improve its metrics.

The extra spending seemed to pay off when the university was awarded preeminent status by the state in 2018, cracked the top 50 in one national ranking of public universities in 2020, and won a chapter of Phi Beta Kappa, the nation’s oldest and most prestigious academic honors organization.

But boosting its metrics in student success and research achievements came with a wrinkle: The administration used one-time cash reserves to cover some expenses that would recur each year.

That means that as some of those expenses come due each year, the university faces a financial quandary that has had some faculty leaders hotly questioning USF’s budget planning process and its fixation on preeminence and rankings.

The university administration declined repeated requests from The Crow’s Nest to address questions about the budget, instead releasing a rosy statement about the 2021-2022 budget and plans to develop “a new budget model … that will provide greater transparency and predictability of funding.” (Read administration stonewalls budget below).

But in postings on its “Strategic Realignment” website earlier this year, the administration said USF needed “to identify permanent funding for investments made in previous years to attain the state’s targets for preeminence and performance-based funding metrics or, alternatively, were designed to meet regulatory requirements.”

The university made “$57 million of investments … in programs without permanent funding identified,” the administration said.

“Many recurring expenses were paid with nonrecurring … funds with the expectation of future state support” that did not materialize, the administration said.

That reality comes at a fraught juncture for the university as it struggles with the challenges of COVID-19, a change in leadership, and a clash between administrators and faculty leaders — some of whom have repeatedly criticized the administration’s budget strategy and its preoccupation with preeminence and rankings.

For now at least, the budget crisis has apparently eased.

The huge COVID-19 relief package pushed by President Joe Biden and approved by Congress in March helped USF avoid most of the deep cuts it was making in its 2020-2021 budget and more it was contemplating for 2021-2022.

Soon after that, a June report by the university’s internal auditors concluded that there was enough money in the consolidated university’s educational and general fund to cover previous “commitments” for recurring expenses.

Tim Boaz, who as president of the USF Faculty Senate repeatedly challenged the administration’s budget planning, now says the auditors’ report was “the final piece of evidence that was needed … to convince the administration” that “draconian cuts” were not necessary.

While the Faculty Senate’s immediate concerns have been resolved, Boaz said, the university still needs to “develop a budgeting process that is more transparent, inclusive and predictable.”

‘U Stay Forever’

For years, people liked to joke that USF stood for “U Stay Forever” — a fitting label for a commuter school with easy admissions standards and a low graduation rate.

That changed with Judy Genshaft.

During her 19-year presidency, the hard-charging executive orchestrated a dramatic increase in the academic profile of the Tampa campus.

That campaign paid off in 2018, when the state named USF Tampa a “preeminent research university,” a designation created by the Legislature five years earlier to encourage the state’s 12 public universities to strive for excellence and national recognition.

Legislators established 12 metrics, or benchmarks, that include average GPA for first-time-in-college students, research spending, student retention and graduation rates, and size of endowment.

Universities that met or exceeded 11 of those 12 metrics would be awarded preeminent status, bringing a jolt of prestige and millions of extra dollars from the state each year.

When USF Tampa joined the University of Florida and Florida State University in that elite group three years ago, Genshaft hailed the milestone in a university news release.

“This validates our efforts over more than a decade to transform USF into a premier institution of higher education, rivaling peers twice our age,” Genshaft said.

That same year, without warning and with little debate, the Legislature voted to abolish the independent accreditations of USF St. Petersburg and USF Sarasota-Manatee and put all three campuses under a single, consolidated accreditation, effective in July 2020.

The two smaller campuses had lower metrics than the Tampa campus, and some feared that might jeopardize USF’s newly won status.

One of them was Genshaft, who made retaining preeminence her administration’s top priority.

“Strengthening Florida preeminent university status for the (unified) University of South Florida is absolutely, absolutely our No. 1 goal and everything else falls in place with preeminence,” she told the Board of Trustees in January 2019.

When Genshaft stepped down six months later, USF was climbing in the national rankings of schools published annually by U.S. News and World Report. It had won a chapter of Phi Beta Kappa and had set its sights on joining the Association of American Universities, which describes itself as an organization of the most distinguished universities in the country.

A daunting deficit?

It was also facing what the administration of then-President Steve Currall sometimes called a “structural budget deficit,” which in simple terms means that expenses were exceeding revenues.

To pull up its metrics, USF spent heavily on people, marketing and support services. And many of those “recurring expenses” were paid with “non-recurring funds.”

Recurring funds are revenues that continue year-to-year in the university’s budget. Non-recurring funds are available one time for a particular purpose.

Non-recurring funds are normally used for capital expenses like buildings and large equipment, not for ongoing operating expenses.

In focusing spending on boosting metrics, the university was counting on a continuation in the way the state funds its 12 public universities.

But the Legislature and state Board of Governors changed the rules, creating new restrictions on how universities can use “carry forward” (unexpended) dollars.

Worse, for the last three years in a row, the Legislature has awarded no new preeminence money to USF and the state’s other two preeminent universities. (The preeminence money awarded in previous years, however, is still part of the three universities’ recurring budgets.)

How deep is the budget hole? That depends on whom you ask.

For months, the administration said its “strategic realignment” of the university’s priorities and budget would require $56.9 million for the year ending June 30, 2022.

As time passed, that figure came down to $30.8 million, according to Boaz, the Faculty Senate president.

But Boaz, who also serves on the 13-member USF Board of Trustees, took issue with that figure, contending that there may be little or no deficit at all, but merely an accounting problem associated with arbitrary decision-making.

He and other faculty leaders accused the administration of “apparent financial mismanagement,” declaring that administrators were capitalizing on the confusion surrounding the budget to make hasty changes in the university’s budget without sufficient faculty input.

In addition to being perturbed about unanswered questions related to what Boaz labeled the “so-called budget deficit,” the Faculty Senate criticized the administration for proposing pandemic-related budget cuts that were overreaching.

They pointed to a remark they say then-President Currall made to the trustees: “Never let a crisis go to waste.” Faculty members were growing concerned that crucial funds would be taken away from immediate academic needs to promote loftier goals for preeminence and high national rankings.

What expenses make up the $30.8 million the university now needs in recurring dollars?

According to a table created by the administration, the largest piece is $10.1 million for the USF Foundation — a private, not-for-profit fundraising arm of the university — for “partial funding of donor and alumni cultivation.”

Next comes $7.2 million for academic and student support for investments that were “key to the increases in performance rankings by USF” such as lowering class size and costs for visiting instructors.

Other categories that need to be covered include $6.3 million for information technology; $2.4 million for branding and marketing for “recruiting top-tier students and faculty” to increase USF’s rankings; and $2.3 million for minimal maintenance and repair of the university’s infrastructure.

Although the university’s auditors confirmed in June that recurring funds are available in the consolidated university’s educational and general fund to support cost commitments made from July 2017 through May 2021, Mike Griffin, chair of the trustees’ Finance Committee, said there are still decisions to be made.

“We still have some needs that we need to address from a structural perspective. I know there’s discussion around what that amount is,” Griffin said on Aug. 4, when the Finance Committee voted on the 2021-2022 operating budget. “I just want to note that as we approve this, we still need to address those recurring and structural issues.”

On Aug. 24, the Board of Trustees approved a legislative budget request for adding $50 million to USF’s annual operating funds for “a recurring investment of new state dollars” beginning in 2022-2023 for costs associated with preeminence and national ranking priorities.

The total state appropriation to USF’s operating budget in 2020-2021 was $434.2 million.

A breakdown of funds the university is seeking to “enhance USF’s overall national and international academic reputation” includes $35.2 million for 175 “high-performing” and “additional” USF faculty and support personnel, and $5.5 million for undergraduate and graduate student recruitment and support.

Administration stonewalls on budget

On May 29, June 4, June 17 and Aug. 24, The Crow’s Nest emailed the university administration to request an interview with a budget or financial administrator who could address budget concerns raised by the USF Faculty Senate and answer questions about the large deficit the administration said it was facing.

Some of the questions the newspaper submitted were:

** In 2019, did former President Steve Currall walk into a budget deficit from the Genshaft administration? If yes, what was the amount?

** What did President Currall intend to convey about his budget strategy by saying “never let a crisis go to waste?”

** As budget concerns played out in recent months, faculty leaders have called into question the administration’s relentless emphasis on preeminence, national rankings and AAU membership. How do you respond to that criticism?

** The administration has said it needs $10.1 million for the USF Foundation for “partial funding of donor and alumni cultivation” and $2.4 million for “branding and marketing.” What would you say to faculty members who are concerned that money will be taken away from immediate academic needs for foundation expenses?

On Aug. 30, the university sent a three-sentence response from spokesperson Althea Johnson that did not address any of the newspaper’s questions:

“We are pleased the USF Board of Trustees voted to accept the proposed FY 2022 budget, which reflected many hours of consultation with deans, the President’s Cabinet, the Regional Chancellors and the Faculty Senate Executive Committee, including department chairs and branch campus representatives.

“We are now looking ahead to the coming year and the development of a new budget model for USF that will provide greater transparency and predictability of funding. USF leadership is committed to working with stakeholders throughout the university to develop this new budget model.”

A similar failure to receive clear, direct responses from USF Administration to clear, direct questions put to it has been typical of the Faculty Senate leadership’s experience since the announcement of the massive proposed cuts to be made in response to the so-called “structural deficit”.

Interesting how everyone selects the best College Ranking survey available. Check Wall Street Journal College Ranking of fall 2020. Somewhere in the 170’s as I recall. Their ranking I believe gave emphasis to undergrad outcomes 5-10 years after graduation. WSJ 2021 ranking not out yet I believe.